Looked at on a table-top globe, the US and South Asia cannot be seen together. Yet, as Srinath Raghavan has shown us in this gripping survey of the 230 years of the relationship, the two have always mattered to each other. In the decades after its independence, the US developed important commercial ties with the region. In the ensuing decades and centuries, motivated as much by commerce as its self-image as the City on the Hill destined to global power, American missionaries, development experts, social workers, diplomats and soldiers impacted the life of this distant region.

The writer, a former army officer, is one of India’s finest modern historians with two important works, one on the strategic history of the Nehru years and another on the global history of the 1971 Bangladesh crisis, to his credit. This book is different in that it is based not so much on archives, but on secondary sources because of its sheer spread. But Raghavan’s mastery has been in bringing together a vast trove of material to write this eminently readable history of the US in South Asia.

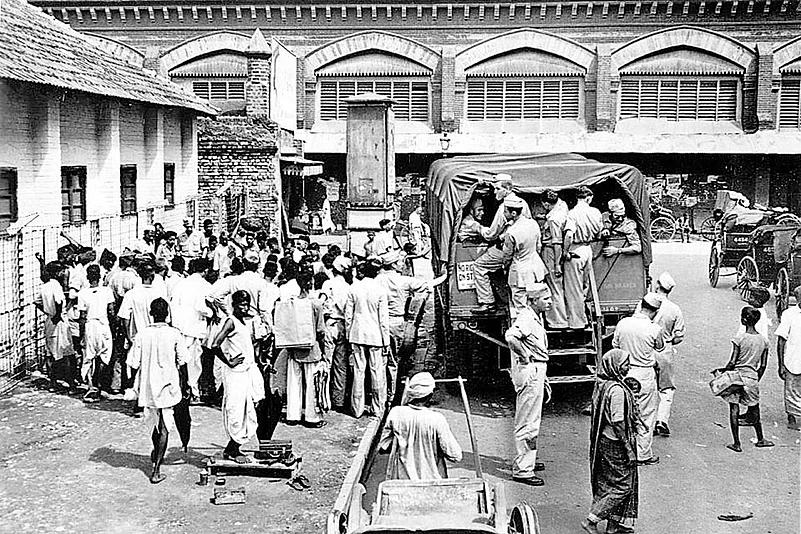

American troops in Calcutta during WWII. They left a deep impression.

In the sprawl of its global interests, South Asia has never really been a principal focus of US policy. The depth of its involvement—in North, West and Southeast Asia—have been marked by the fact it has fought wars in Korea, Vietnam and Iraq. Though the Afghan wars beginning in 1980s did bring it to the periphery of our region.

It is not as though this was foreordained. As Raghavan shows, the US had an intriguing relationship with the region in the early 19th century. It was based on American interest in trading with India, but also motivated by saving souls. At the turn of the century trade was good. The British were still in the process of consolidating themselves in the subcontinent and fighting a major war in Europe. So, American trade with India in the decade following 1795-96 “exceeded the combined total of all European ships by 25 per cent.” But it suffered a steep decline after British and French measures compelled the US to pass the Embargo Act in 1806 and following the war of 1812.

As for saving souls, interest in India came with the Great Awakening, one of the periodic religious revivals that the US has had. The American Missionary Society sent some missionaries to Calcutta, but the British refused to let them land: it was 1812 and the two countries were at war. But the governor of Mumbai was not too choosy; he had the task of governing a pestilential swamp and he felt there was always need for some White teachers and social workers. The American Marathi Mission thus became the foremost of the labours of the AMS. But work was tough; it was only in 1830 that they managed to ‘save’ their first Hindu.

The rapid shift in America’s own economic profile towards domestic construction and consumption led to a change in the profile of its trade with India. Through the century, even as Indian textile production collapsed, indigo, leather, saltpetre (for gunpowder), linseed and jute found markets in the US. In return, India got factory manufactured cloth like jeans and drills and heavy twilled cottons, newer goods like glassware, clocks and the favourite, tobacco. Between 1833-1860 ice, cut out of the ponds of New England, was an item of import by the British elite in Calcutta and Chennai, being sent in double-hulled ships along with apples and butter. Frozen out of India by British imperial trade rules, the Americans ‘discovered’ China and the traders and missionaries shifted focus.

A third strand of the Indian and American connection came in the 19th century through the contact with Hinduism. Some aspects of the faith, sati, the treatment of widows and idolatry repelled them; others, such as the philosophy flowing from the Upanishads attracted intellectuals like Ralph Waldo Emerson. Raghavan has done signal service in pointing to this often neglected area of interaction, which otherwise confines itself to Swami Vivekananda’s American tours.

Through the 19th century, American attitudes towards India waxed and waned. To an extent they were influenced by the racial theories of the day and to some extent with the belief that the British Empire was effete and would soon be replaced by a more vigorous proponent of progress and faith—the United States.

The fourth strand, the political one, only came after the US came to South Asia as a Great Power in World War II. Their focus was on the war with Japan and in helping out China, whose armies had retreated to Chongqing. This is another forgotten chapter, considering that the number of Americans in India grew exponentially. Many of the airstrips and military facilities that our military still use were constructed by the Americans in their preparations to fight the war against Japan more effectively than the British.

In the 1950s, through its military alliance with Pakistan, the US did India great harm that led to the complete alteration of the regional dynamics. In the early 1950s, Pakistan had generally settled into its position as the smaller of the two powers in the region and was ready to do a deal on Kashmir. But American jets and tanks soon revived their dream of being equals of “the Hindus”; the war of 1965 was its most direct consequence.

Then, the US compounded it by its support to the Yahya regime in 1971 and finally by supporting a jehad to bring down the Soviet Union. By using the INStrumentality of Pakistan and Islamist rebels they helped create the jehadi Frankenstein’s monster, and Islamabad was given a free pass from the US’ own non-proliferation rules to press ahead with its bomb. The Chinese only confirmed these altered dynamics by enabling Pakistan to make nuclear weapons and missiles.

But the US also did a lot of good as well. In the 1950s and 1960s in compensation, as it were, they also provided a vast amount of economic assistance to India and certainly saved millions from starvation through their PL 480 sales. Along with it came expertise in reforming our educational system, setting up engineering colleges, training scientists and helping trigger the Green Revolution. As Raghavan notes, “encounters with America were a crucial aspect of South Asia’s encounter with modernity”.

Somehow, the writer notes, the US has never quite managed what he says is a “stable hegemony” in South Asia. The reason for this is that though they are on two ends of the affluence scale and on opposite ends of the globe, the US and the region’s principal state, India, are quite alike in some ways. Both are prickly, preachy democracies with a sense of exceptionalism and entitlement.

Even today, the US retains its ability to do great good, and harm, to us. This is the reason we need to understand the drivers of its policies, some of which, as Raghavan shows us through the book, go back deep in its history. There is a tendency in India to believe that everything you want to know about the US is available through its media, its open people and policies. That’s simply not true; there are depths and motivation that require greater expertise to uncover and analyse, especially since the country will remain the foremost power of the world through this century as well.

(The writer is a Distinguished Fellow, Observer Research Foundation)