This is a book about imagined lives. It is also a story of divisions—divisions between husband and wife, between parent and child, between brothers, nations and between ideologies. Set in the 1930s, All The Lives tells the story of Gayatri, who as a teen wandered Indonesia with her father and met ‘Robi Babu’ (Rabindranath Tagore) and his entourage on a ship, and was never the same again. It is also about her son, Myshkin, who takes his name from Dostoevsky’s Idiot, adores his mother and tries to figure out why she left him.

Gayatri sees herself as meant for a different kind of freedom—escape from household bonds. She is an artistic soul forced by her father’s death to obey her conventional relatives. Though rescued from the typical arranged marriage by her father’s student, she finds herself “cabined, cribb’d and confined” by a husband whose ideologies clash with her own.

The problem is, Nek Chand Rozario finds that the girl he married is too wild for him to handle and despite his respect for Gayatri’s father, he appears to have a strong streak of patriarchy that makes one wonder, why the sudden impulse? His notions of freedom are very different from those of Gayatri—civil liberties rather than artistic ones.

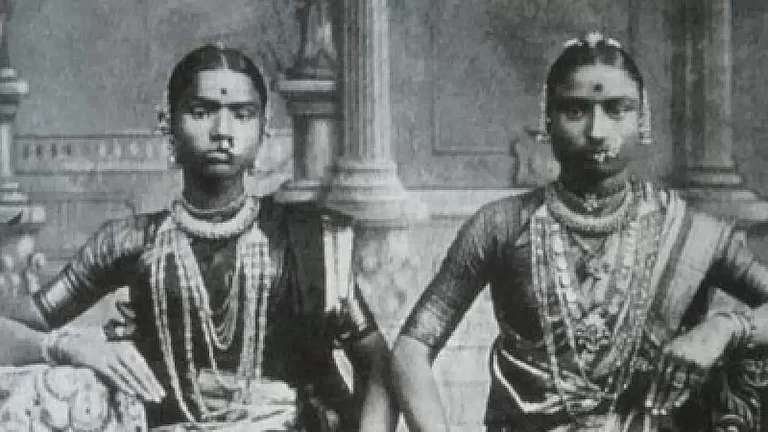

The result is that his rescued bride eventually encounters a German from her wandering days and erases herself from the boring household canvas. What Roy keeps under smoke and mirrors in the wake of the disappearance is the fact that Walter Spies—who was a real person steeped in Indonesian art and music— went everywhere with a female companion. No one in the town of Muntazir seems to remember the striking Beryl de Zoete and the general assumption is that Gayatri has eloped and shamed her husband.

Roy tells the first part of the story from Myshkin’s point of view—a child who was supposed to have come home early from school the day his mother left and who realises that she intended him to go with her. However, she does not return and he suffers agonies over what the neighbours might think. Perhaps, remembering Beryl may have made matters easier, but she stays forgotten and the lives of the Rosarios jerk unevenly along, with Nek Chand finding solace in his nationalist work, Myshkin’s grandfather trying to hold the family together and Myshkin becoming more and more of a loner. Aptly, given Myshkin’s plight, the place that Roy describes is called Muntazir, which means ‘to wait’.

Roy throws in all the people one might expect from a small town in those days before communalism—the aggressive, rich neighbour Arju Chacha whose brother Brijen is a musical aficionado; Lisa, the single Anglo-Indian woman who shares Gayatri’s passion for dance and Nek Chand’s wife, Lipi, a widow whom he rescues with her small daughter.

It is obvious that Nek Chand’s attempts at rescue are doomed to failure—Lipi struggles against his homespun nationalism and destroys the contents of Gayatri’s cupboard in an attempt to attract attention. Nek Chand finally does notice her, but too late—he is arrested for his nationalist activities with the outbreak of World War II.

This is when Gayatri reappears through a series of letters and the reader realises that there was no romantic relationship with Walter Spies—apart from the fact that Beryl was there all along, Walter is gay. Gayatri’s true love was someone else altogether and the relationship is counterpointed by generous quotations from Maitreyi Devi’s novel, It Does Not Die, which misdirect the reader to begin with—since the young Maitreyi had a covert relationship with a non-Indian. Gayatri’s secret passion, however, turns out to be a brief fling with an Indian, but she chooses to follow the path of art rather than her heart and returns to Bali and her idyllic memories.

Roy describes Gayatri’s life in Bali with well-researched touches—Bali is the India of the bygone days that inspired ‘Robi Babu’ and that continues to inspire Gayatri, despite her pangs of guilt and loss. However, she can never summon up the courage to abandon her art and return to her son until it is too late—the war gets in the way.

Myshkin grows up into a horticulturalist against his father’s notions of nation-building and splashes the streets of Muntazir with bright flowers that recall his mother’s canvases; when he finally reads the letters, his life comes full circle and the waiting ends with a departure.

All the Lives is a slow-paced novel written with Roy’s usual lyricism. Life, she implies, should be grasped with both hands, instead of lingering in the land of what might have been.