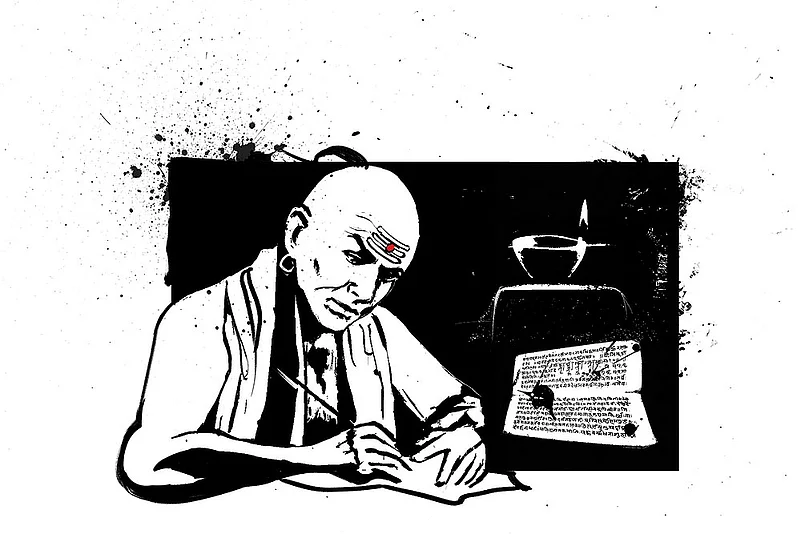

At the Mysore library, now known as the Oriental Research Institute, the Arthashastra is presented like a sumptuous dish, or a holy icon, on a plate bedecked with fresh flowers. Their scent mixes with the smell of citronella oil, which the library uses to preserve its store of palm-leaf manuscripts. The pages are held together by a single length of string, and filled with the beautifully precise letters of the 1,500-year-old Grantha script. They almost look as if they have been printed, but the words have all been meticulously inscribed by hand.

This manuscript would have been produced more than a thousand years after the Arthashastra was first composed. The original author is thought to have been Kautilya or Chanakya. Some have argued that he was the minister of Chandragupta, who, in the fourth century BC, laid the foundations of the Mauryan empire, India’s first, and for a long time, its largest, imperium. Although the manuscript would be forgotten, Kautilya or Chanakya became the subject of stories and legends.

As far back as the Gupta empire, in the 5th century AD, we find a dramatisation of the life of Chanakya or Kautilya—both names are used, along with a third one, Vishnugupta—set in the Mauryan court. The Sanskrit play Mudrarakshasa or ‘The Ring of Power’, by Vishakhadatta, sought to embellish the imperial ambitions of the Guptas by linking their reign back to the era of the Mauryas, some 700 years previously. It is an early example of the kind of appropriation of past lives that recurs across Indian history. In the 5th century AD play, Kautilya comes into possession of a signet ring belonging to the minister of a rival king, and uses it to impersonate and intrigue so that his own king ascends to the imperial throne.

In another popular story, Kautilya overhears a mother telling off her hungry, impatient child for burning his hand by sticking it in the middle of a bowl of hot gruel. Eat from the edges of the bowl, the mother says. It’s cooler there. From this, Kautilya develops an innovative theory of conquest: don’t attack an opponent’s capital—move in, stealthily, from the periphery. As a result of such stories, Kautilya is often presented as the Bismarckian mind behind Chandragupta Maurya’s conquests. Sadly, recent scholarship says the dates of the two men don’t align. But if Kautilya the man remains veiled, the Arthashastra itself stands out within the Indian tradition—and beyond. The conception of power it embodies includes military might, but goes well beyond it, encompassing the use of wit and intellect, as well as guile, cunning and deceit.