President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam was immersed in work till his last day. He was in Shillong on July 27, giving a speech to IIM students, when he suddenly collapsed. Here are exclusive excerpts from President Kalam’s last project, the forthcoming book Advantage India, co-authored with activist and writer Srijan Pal Singh, in which he draws upon his own life to illustrate how India can win.

***

In July 2014, both of us (I and Srijan Pal Singh, my co-author) visited the Jaunpur district of Uttar Pradesh to attend the National Children’s Science Congress, a platform that provides children from all over the country an opportunity to make their dreams come true using their scientific temperament. July is a hot month in this eastern Uttar Pradesh district. Coupled with dry weather and strong winds, the soil often comes loose and makes the air dusty. Such weather conditions may often last for several hours through the day and obscures one’s view.

We began our journey on the national highway. About two hours later, our convoy of five cars and a mid-sized van started moving into roads that became progressively narrower. Soon we reached an area where we were engulfed in a thick cloud of dust. Visibility was low, our only guide being the car ahead of us whose driver had thankfully switched on its tail lights to help us follow better.

I asked Srijan, “Are we on a road or have we lost our way on some kuchcha (mud) track?” He pulled out his mobile phone and switched on the GPS. To our surprise, in the midst of all the dust, the internet on the cellphone was able to function on the high-speed 3G network. On Google Maps, a moving blue dot indicated our position. All along, we were moving on a state highway—a supposed rapid movement road.

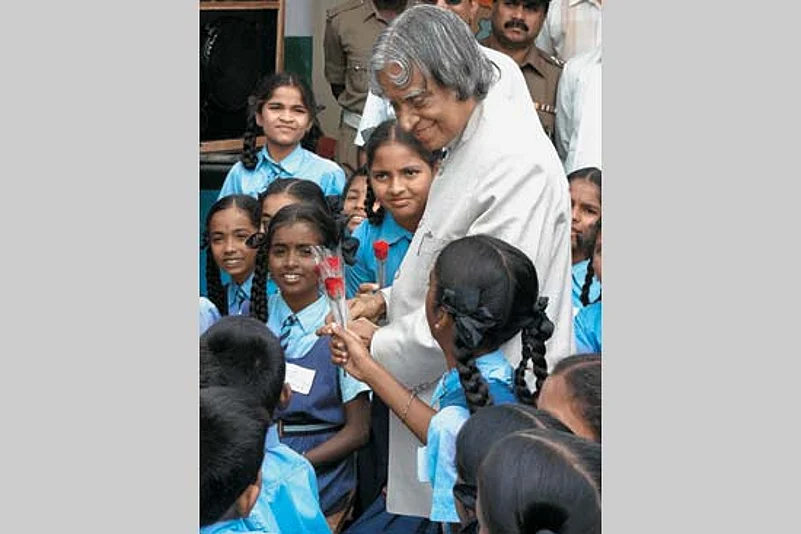

Darling buds Schoolchildren offer roses to Dr Kalam during a visit to a Bangalore school. (Photograph by Reuters, From Outlook 10 August 2015)

Another hour passed like this. Significantly slowed down by poor visibility, we fought a losing battle against time. Then we hit a stop. Our driver told us there was a railway crossing which was shut and we would have to wait five minutes. As the tyres stopped rolling, the dust around us settled—and for once we got a clear view of our surroundings. The board of a nearby shop told us the name of the area: Badshahnagar, or township of the king. Going by our description of the road, you may think that the name was ironic. But that was not the case, at least not entirely. The settling dust showed us things; it was almost like a revelation of the potential of Badshahnagar.

First, we saw hoardings wooing customers to use mobile money transfer. M-Pesa, a product started in Kenya by a non-governmental organisation and then taken over by the multinational Vodafone, and Airtel Money, a service offered by an Indian-grown multinational, fought for advertising space in the market near the railway crossing. We later learnt that most of the workers who had migrated from eastern Uttar Pradesh to Delhi or Mumbai frequently used mobile transfer to send money back home. Half of those receiving the money could barely read the dial pad on their phones, but nearly all were able to manage the transactions effortlessly. The pressing need for rapid money transfer had led them to skip the stage of basic literacy and land straight to digital literacy (or ‘m-literacy’, which stood for mobile literacy, an even fancier term).

Second, at a slight distance, our eyes caught a glimpse of a couple of training centres located across the crossing on the first floor of a building. One was called ‘Maruti Computer Training Centre’ while the other was called ‘Sai Mobile Repairing Centre’—the former named after Lord Hanuman, the other after Sai Baba, a spiritual leader only about one hundred years old. These two skill development centres thus represented how India’s remote areas stay abreast of the most advanced technological consumer tools of the modern era.

But there was more to the story of these two centres. Below their names were listed a set of diploma courses they offered. Then the winner line: ‘Courses in Hindi, English and Bhojpuri’, followed by ‘Special 20% discount for girls’. We could not help but smile at Badshahnagar’s inclusiveness of people of all languages and genders. Was it not a true mark of a king’s land?

Students interview Dr Kalam for Outlook, Dec ’03

As we proceeded, all along the highway we noticed a number of small shops huddled together—many selling tea, snacks and clothing items; an occasional air-conditioned restaurant; an electronics store and some pharmaceutical shops. In their diversity and balance of commodities, they represented ‘horizontal supermarkets’. There was hardly anything one would not find in these stretches of shops. There was no plan, no dedicated corridors or floors. The entire structure was organic.

We wanted to get a feel of these rural commercial spaces. So, in the middle of our journey, we decided to stop and enter a small tea stall. Some of the choicest Indian dishes were displayed under a glass top: samosas, pakoras, jalebis and barfis. At the counter was a refrigerator stacked with colas of international brands that jostled for space with the local tangy drink known as ‘banta’—carbonated lime juice with rock salt and sugar. Seeing a large convoy with many policemen, the shop owner quickly came out from behind the counter and placed a few plastic chairs along a small table. He told us his name was Kuber, named after the divine custodian of wealth.

Kuber had an air of confidence about him as he replied, “Everything here is fresh. The stacks are replenished twice a day.” Then he added, “I am a specialist in tea flavours.”

Encouraged, we asked him what he meant. In response, he gave us a sheet of paper, wrapped neatly in clear polythene. ‘Tea Menu’, it read. On that menu, he had listed at least a dozen different tea flavours—ginger, lemon, chocolate, pudina (mint), Darjeeling and many other variants. It was surprising to see such imagination and innovation in a little shop on an obscure highway. We quickly ordered about a dozen cups of tea for all of us, along with some samosas.

Immediately Kuber and his helper washed the utensils, mindful of good hygiene practices. In five minutes, all the items we had ordered were laid out on the table. It was one of the most refreshing cups of tea I have had. While we had the tea, Kuber told us he lived not far from the stall, that the helper was his nephew, that he had two daughters, both of whom went to school and that business was generally good.

We had a few takeaways from the examples of Badshahnagar and Kuber’s tea shop. First, they showed us how local markets create entrepreneurs. Second, how these entrepreneurs innovate. Third, what form enterprise can take in a local context. We had some questions, which became the basis of our discussion: how do high-speed mobile internet connections work seamlessly where roads barely exist? What can be done to promote in-house brands that serve as the backbone of our local economies? Is India a land of dismal challenges or magnificent opportunities?

India has been witnessing a new thrust in policy and planning since 2014. In the run-up to the landmark year of 2020, Parliament and people have endorsed many new missions like Make in India, skill development of the youth, hygiene and health for the nation, smart cities, Digital India, new energy policies and new rural development models. What are the opportunities for the nation for the next four to five years? What are the key challenges to address? And how can we learn from our own experiences and from the lessons of other nations to leapfrog them?

(Advantage India, published by HarperCollins, will be out by October.)