Is there any room for architecture in a country where daily migration destroys all semblance of urban coherence, where people’s desperate demands for subsistence and a bureaucratic stranglehold on large-scale projects allows no experiments on design, where every urban act fights for visibility and survival.

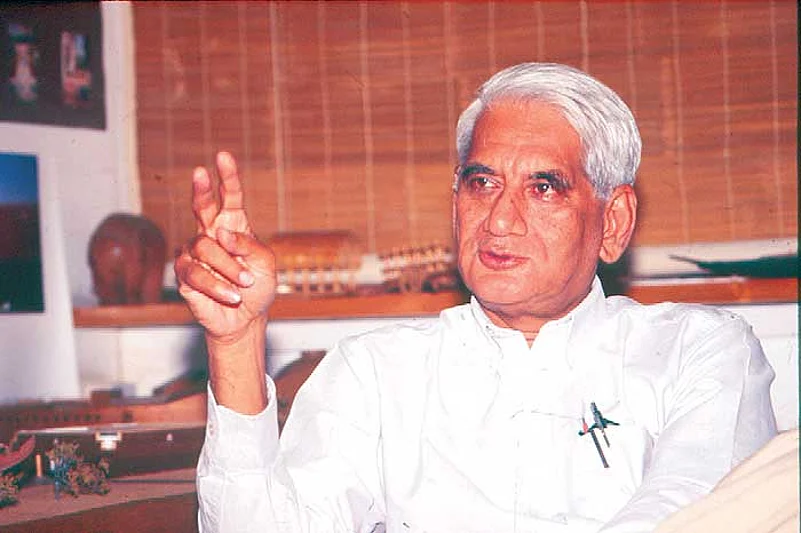

Which is why it’s a wonder that an architect of Charles Correa’s sensibil-ity has not only survived for more than half a century, but has in fact thrived in the mess. The secret of his success is the single-minded determination to make a difference. In a practice that ranges from designing art institutions like the Jawahar Kala Kendra and urban housing for the poor in Mumbai’s Belapur suburb, Correa is highly sensitised to the extreme variables of work in India. His projects are not merely problems to be solved but address situations in full awareness.

In a profession steeped in meaningless jargon, Correa’s writing is refreshingly shorn of verbiage, and this collection of essays is of ideas deeply felt and practised. It’s also a tribute to Correa’s versatility—he can amble as easily from architecture to planning, philosophy and astronomy, without losing track of his original thought. What separates him from other architects is his ease with a vast range of subjects that peripherally—sometimes rarely—affect architecture: Gandhi, religion, education, sculpture, and of course, planning.

At the core of Correa’s work is a deep concern for people, how they live, the cities they make. The grand projects for museums and institutes become only tangential events when pitted against the despair of Indian city life, and Correa the writer expresses his resolve not in statistics and numbers, but a response that comes from acute observation. The high densities of living in Indian cities are deceptive, he writes, because they don’t come from high-rise buildings but “through an extraordinarily high occupancy rate per room”. A cultural rather than a statistical aberration, its solution too needs cultural resolution.

Such innovative thinking so essential to the relentless urbanisation in the big towns is unfortunately stymied by a lack of political will and the bureaucratic fear of responsibility. What will be has always been. The sad ramshackle landscape of the Indian city reflects not just the collective hopelessness of flouted urban norms, construction incompetence, corruption and inadequate standards, but the neglect of a profession that has marginalised itself. So agonising is the daily reality of Indian towns that it is hard sometimes to share the optimistic tone of Correa’s book, the belief that the blurred mythic image of skyscrapers in a foreground of shanties is one of aspiration, and not despair.

In his own work, Correa’s inclusive perspective often exceeds the more modest expectations of clients used to cramped lifeless buildings, doomed to a life in glass or blemished plaster walls. Ideas about public to private, the mundane and the sacred, order and chaos, have all preoccupied Correa throughout his architectural commissions. Suggestions of these first appeared in the Sabarmati Museum in Ahmedabad, an additive of square modules that moves you, square by square, into a carefully structured sequence of the life of Mahatma Gandhi. In later projects, Correa used history in personal and symbolic ways: at the Jawahar Kala Kendra the plan was a simulation of the Navgraha, a geometric version of the cosmos; at the Pune Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, the Big Bang was signified by the empty centre. Obviously in these literal interpretations, the translation of cosmic themes to day-to-day buildings, the architect may be extracting more than his fair share of artistic licence, but the accusation is irrelevant. The mode of innovative communication is the very value Correa asserts in his architecture.

If Correa’s place in Indian architecture is assured, it comes at the cost of critics unable to put his career into a straitjacket. A modernist with a deep sense of history, a romanticist who uses imagination pictorially and sculpturally, and an optimist who still believes in the future of the Indian city, Correa thankfully remains outside the ordinary circle of architecture. For an architect who has spent so much time under the Goan sun and in the breathless tumult of Bombay, his book will raise enough questions to realign our thinking. Less architectural memoir than a collection of deep personal insights into living and building in India, Correa has at least found his place in the shade.