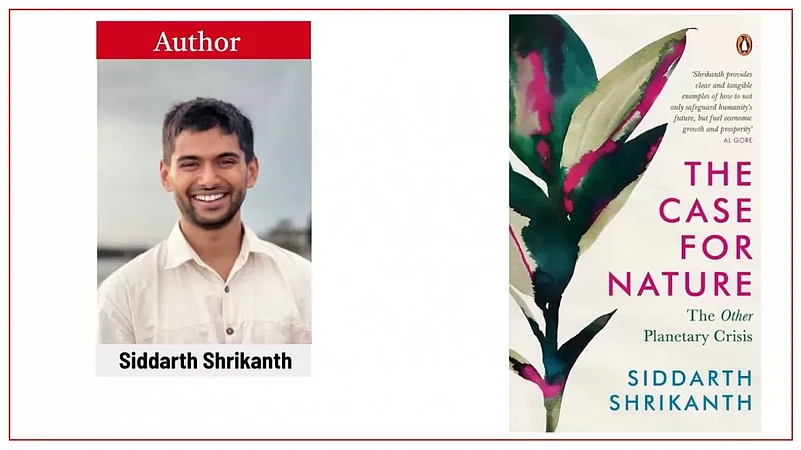

Never before has Earth’s biosphere been so disproportionately impacted by a single species, writes Siddarth Shrikanth, referring to human beings, in his book The Case for Nature: The Other Planetary Crisis. He begins making his case by talking about the impact of human presence on nature and the biodiversity on the planet. Making the case for nature requires one to balance the head and the heart, he writes.

Climate and biodiversity crises are deeply intertwined, but they are ultimately distinct, Shrikanth explains. “I chose to focus this book on nature in part because I noticed that those around me—the current or the soon-to-be leaders in their respective fields of business, technology or policy—were responding to the energy-climate challenge while often remaining in the dark about the extent and importance of the biodiversity crisis,” he says.

Shrikanth feels that from every conversation that he had on the subject, he learnt something about the collective failure to communicate the urgency of the “other” crisis, which was to “to pluck nature from the realm of the nice-to-haves and place it firmly within the universe of existential questions”. According to him, natural capital must be elevated to have the prominence equal to that of financial capital.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

Central to the case I want to make are a set of ideas and recent developments that are grounded in the notion of ‘natural capital’. The baseline of this approach is that, in and of itself, the natural world is priceless – but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t also have value. We are all familiar with the concepts of financial capital, human capital and social capital. Natural capital is simply a framework that can allow us to recognise a sliver of the value that we derive from the natural world: the ways in which our natural assets, like forests and oceans, can provide a range of ecosystem services that represent economic and social goods. These services range from tangible ones like clean air and water, carbon storage, fertile soils and pollination, to the intangible cultural and spiritual value that complements them. If we are to meet the imperative to protect and restore our planet, we can no longer treat nature as a distant wonder to be enjoyed on occasion before we retreat once again to modernity: natural capital fundamentally underpins our wellbeing and deserves a central place in our economic framework.

In an economy roiled by crisis after crisis, it can feel at times like the only option we have is to rip up our current system and start over again, embracing degrowth or dramatically curtailing the market economy. But the ‘market’ is a social construct, and one that has largely been governed with a narrow set of financial aims in mind. With time running out, I argue that we need to make a serious effort to fold nature’s value into the system we already have: one that has, to its credit, brought remarkable progress and improved living standards for many, but has clearly gone too far in the direction of environmental destruction.

The Nature Lover

Shrikanth’s interest in nature is not newfound. “I have always had a sense of wonder in the natural world. When I was younger, my curiosity took me to nearby forests and beaches, or to the hundreds of natural history books in family’s library. I have had the privilege of spending time in some of the most incredible ecosystems in the world,” he says.

According to him, the book renewed his respect for indigenous cultures, practices and worldviews “that have too often been lost in the debate on saving our planet”. Seeing ourselves as custodians of our living planet through deep time can lead us to make decisions differently, he argues, adding that sustainability takes on a deeper meaning when it operates on millennial, rather than quarterly, timescales.

Perhaps the most important, and most personal, step is to cultivate a sense of wonder in nature that lives deep within all of us, he avers.

What Next

According to Shrikanth, the inspiration for The Case for Nature came from the success of the climate movement. He is also optimistic about the future of such efforts. “Cutting greenhouse gases has gone from a fringe environmental argument to an urgent economic imperative that we can build careers and companies on,” he says.

He is clear that he will continue working on the biodiversity crisis. For his next venture, he is planning to write on nature and history.