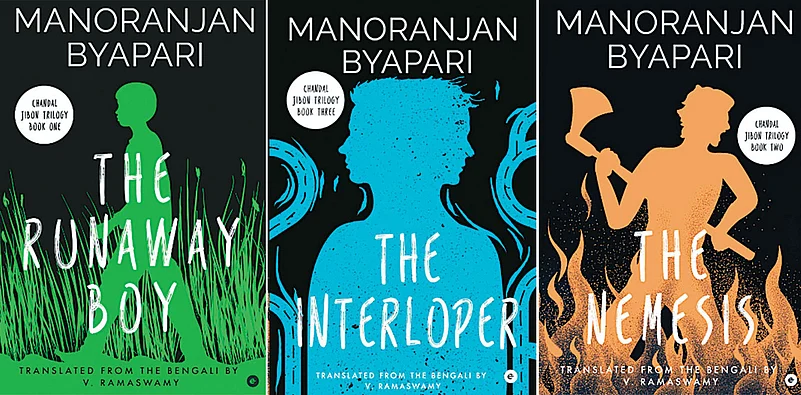

Manoranjan Byapari’s The Interloper is woven around a Jibon-like person, who ostensibly impersonates being Jibon. The stranger soon realises that being Jibon (life, a life-giving force) is not just about being a person, but a thought and a force that bring hope to the most hopeless born and living in squalor.

The socio-political wisdom that Manoranjan Byapari shares in the novel through the characters is a testament to his ability to see through layers of social formations as they existed in post-partition Bengal. V. Ramaswamy has done full justice to his role as translator, lending a voice to the felt story Byapari narrates.

The Interloper takes the reader through many lives, each harsher than the other, living in decrepit conditions in Calcutta and yet, desires, attractions and follies are the same for all, irrespective of class or status. When Surabala reaches out to the stranger, professing her love for him, there is desire as well as a social need. While the justice meted out to Golam for kidnapping the kid Yadav is a result of rage, it is also a depiction of what people in the most impoverished conditions are not ready to overlook. To the reader this moment of anguish underlines a hope—certain crimes are just not to be condoned.

Jibon is the protector of the young girl who could have been molested had he not woken up the “Jibon” in him. The story keeps moving from near death to death-defying moments. One almost begins to hope that this basal existence is not real and it is just a story you are reading. But since it is a semi-autobiographical work, each chapter leaves you pained about how there can be so much disparity in human lives. That is a question which is sure to daunt anyone who reads this book because presumably, if you are reading this book, you have never had to exist in the space these characters occupy. They are lively and hopeful at times and ready to kill at any moment.

Many of the people staying on or near the Jadavpur station are not just living impoverished lives. Each chapter brings out their hapless misery, waxing and waning; just as Jibon is beginning to build a bit of hope the situation takes an impossible turn. You want to pray that he finds his release but that does not happen. The book leaves you with much to think about in terms of how in a limited microcosm, different layers of caste, religion, greed and machinations of the human mind create webs of destruction, and countless people are pushed to live their lives on the brink. There is a world of happiness, hope, respect, love and care inside the people who touch Jibon’s life, but there is also the cruel, deprived existence they are all condemned to. Crime is not a choice. It is the only way to exist. And so you are left to think about what crime really is and whose perspective the law is made from. When the “home” is a tin roof and the wall is a piece of cloth, what defines the human development index?

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This is a troubling account of abject poverty. Every moment is lived at an elemental level. “Ganesh was seven or eight years old then. He ate whatever people provided him, and when they didn’t, he scoured the dustbins.” Set in the late 1960s and early 70s, the story unfolds in a Calcutta that was plagued by Naxal violence, jobs were few and workers underpaid, tilling land brought no income, social disparities were at abysmally high levels and violence and crime were palpable everywhere in the politically fragmented region. This is a powerful read, which transports you from the comfort of your chair straight to Platform 1 of Jadavpur and lets you meander through shanties and rail tracks as you figure out the meaning of life. Or death.