For 27 long years, Manohar Malgonkar’s manuscript on the 18th century Maratha chieftain Murarirao Hindurao Ghorpade, or Morari Row, or simply Murarrao, lay locked up in a drawer. But curiously, just one month before his death on June 14, the writer took this thick sheaf of pages, typed on an Olympus typewriter, and handed it over to Prof S. Shettar, a historian, hoping posterity might have some use for it.

It may well do. This is a marvellously narrated, quasi-historical account of a fascinating character and is likely to be published soon. The lingering mystery is: Why did Malgonkar keep it unpublished for so long? It seems to relate to the fact that this biography had been commissioned, probably by the Ghorpades, erstwhile rulers of Sandur, in Karnataka’s Bellary region. They derive their surname from the legend of the “ghorpad”, or monitor lizard, reputedly used by Maratha chieftains to scale forts under siege, and claim Murarrao as their ancestor. For some reason, Malgonkar’s manuscript appears not to have passed muster with them.

“I am not aware of the entire story, but it is very likely there was a difference of opinion between them and Malgonkar on the family tree or genealogy,” says Shettar. He also recalls that when he met Malgonkar in the late 1980s, the writer sounded dejected and spoke out against accepting commissioned work. He had then turned down the Maharashtra government’s request to pen a hagiography of Chhatrapati Shivaji.

Interestingly, in 1992, nine years after Malgonkar completed his manuscript on Murarrao, a descendant, M.Y. Ghorpade, produced a brilliantly illustrated book on him, called The Grand Resistance—Murarirao Ghorpade and the 18th Century Deccan (Ravi Dayal Publisher). Ghorpade, now in his eighties, told Outlook he had no idea Malgonkar’s manuscript even existed. “I am intrigued it’s being published now,” he says. As it happens, he is working on an abridgement of his earlier work.

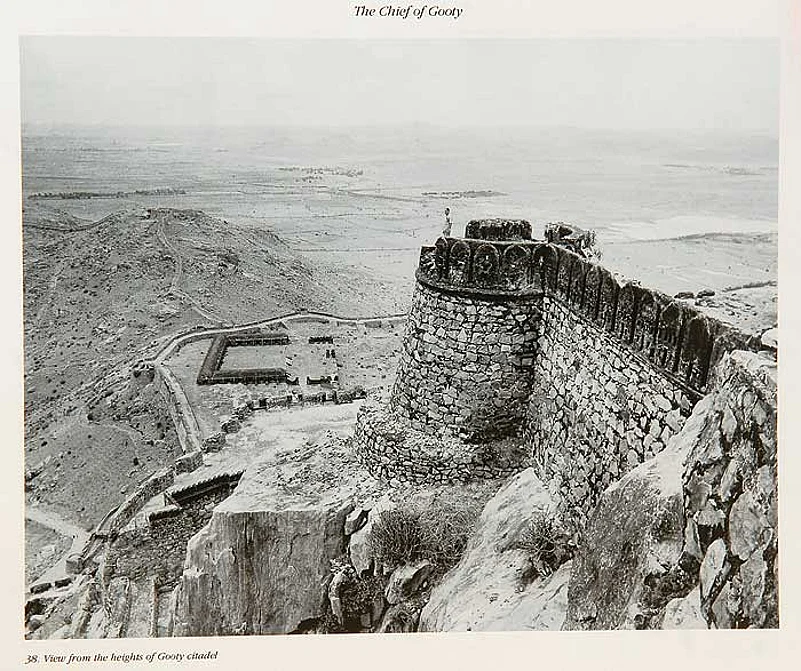

Mysteries aside, what is it about this minor Deccan chieftain that is getting him so much 21st century attention? It has largely to do with Murarrao’s times, his military accomplishments, his fiercely independent personality. Murarrao presided over Gooty (or Gutti), in modern-day Andhra Pradesh, roughly between 1731 and 1776, a time of great transitions. The Maratha army was sweeping over the entire country, the British East India Company and the French were trying to gain footholds in the subcontinent, and the Mughal empire was in steep decline after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707.

And Murarrao was right in the middle, as the Peshwas’ most reliable ally in the Deccan. A descendant of the heroes of the Maratha resistance against Aurangzeb (who failed to dominate the Deccan) and of chieftains who had fought alongside Shivaji, Murarrao received the title of ‘senapati’ from Peshwa Madhavrao in 1764.

But as Shettar points out, Murarrao was a shrewd collaborator who maintained a tactical alliance with the Marathas without sacrificing his autonomy. In a vivid 1940 assessment, historian Govind Sakharam Sardesai said: “Few people in Maratha history had such a romantic career as Murarrao.... [His] was a life of monumental struggle, full of incidents and thrills, of victories and reverses, of stagecraft and foresight.”

Murarrao’s legendary status in this region also comes from his encounters with Tipu Sultan’s father, Haidar Ali, to whom he finally succumbed, but only after holding out for a long time, and even subjugating him on occasion. In August 1768, there was a hand-to-hand fight between the two. But nearly nine years later, in March 1776, Murarrao surrendered when Haidar besieged the fort of Gooty. Captured and thrown into the Kabbaldurga fort near Srirangapatna, Mysore, he is said to have died a year later, aged about 70. But only after having done enough to make his story worth Malgonkar’s close attention and skill some two centuries later.