For far too long, Jawaharlal Nehru has been condemned as a woolly-eyed idealist, whose worldview is held responsible for the festering Indo-Pak dispute and the unresolved boundary issue with China. While traditionalist historians have found him guilty of sacrificing India’s core interests in the pursuit of his ideals, revisionist scholars have viewed him as arrogant and blamed him for his propensity to use force at the slightest provocation to get his way.

Challenging these two schools is Srinath Raghavan’s book, War and Peace in Modern India, which presents the thesis that Nehru was an out-and-out realist. For instance, about India’s defeat in the 1962 war with China, for which Nehru continues to draw flak, Raghavan writes, “Contrary to received wisdom, the problem with Nehru’s China policy was not his idealism but his realism”.

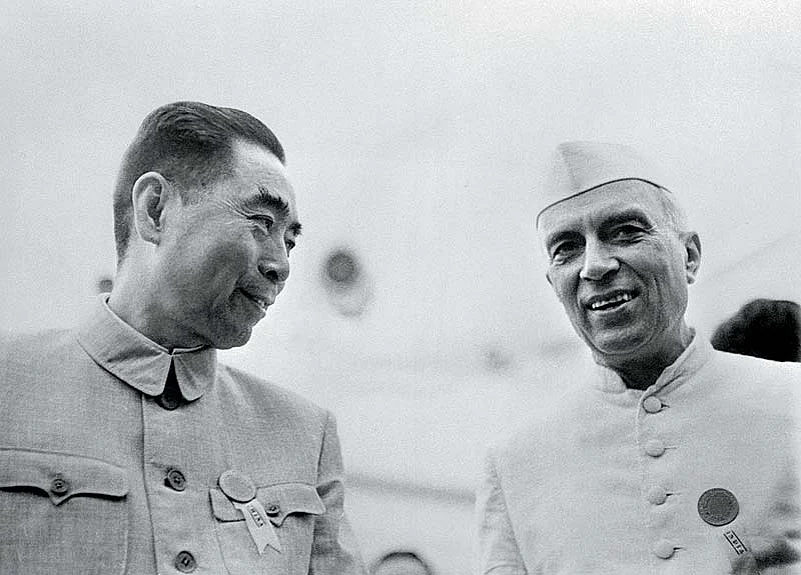

It was Nehru’s belief, Raghavan shows, that the ussr wouldn’t allow China to attack India as that could compel India to move closer to the Americans. Subsequent events showed Nehru had miscalculated. The realist in him had correctly read the situation, but he failed to grasp the role of nationalist ideology in Communist China’s foreign policy—that it would not refrain from military action to reinforce its territorial claims.

Raghavan says Nehru’s failure on China shouldn’t make one oblivious to the sophistication of his approach to strategy and crisis management. Though he “initiated military measures (forward deployment), without risking a full-scale war”, he continued to “pursue diplomatic settlements to the extent possible” to contain domestic opposition.

Contrary to the view held by many scholars, Nehru showed willingness to communicate with adversaries in search of “acceptable compromises”. For instance, when faced with difficulties in going ahead with a plebiscite in three regions of Kashmir, Nehru toyed with a variety of other ideas—partition with or without plebiscite, a limited plebiscite and election to a constituent assembly. A few months before his death in May 1964, he even discussed the idea of a possible confederation involving India, Pakistan and Kashmir with Sheikh Abdullah to find a solution to this vexed problem.

Raghavan’s book isn’t a biography. It is a historical study of his foreign policy, “concentrating on matters most related to the fundamental questions of war and peace”. His attempt is to explain the context of each crisis India faced in the early years of independence, and the options both Nehru as well as his adversaries had before them. Through skilful use of archival material located both within and outside India, Raghavan manages to recreate the context of crises involving the princely states of Junagadh, Hyderabad and Kashmir, demonstrating their inter-linkages rather than treating each as separate events.

Raghavan shows us the array of tools available to Nehru, and the reasons for his choice to resolve each crisis, though at times he opted for a combination of these. This analytical method also provides us a glimpse into Nehru’s understanding of power and its limits. Though a disciple of Gandhi and a key member of the non-violent movement that gained India its independence, Nehru knew that “life is full of conflict and violence”.

The book’s most original chapter is on the 1950 refugee crisis that pushed India and Pakistan to the brink of a war. When Hindu refugees started pouring into West Bengal from East Pakistan, Hindu hardliners began to take retributory action against Muslims in India. Raghavan shows how Nehru opted for “coercive diplomacy”—a method Atal Behari Vajpayee employed against Islamabad after the Parliament attack—compelling Pakistan to stem the flow of refugees.

Raghavan, though, fails to explain why, in the mid-1950s, when a settlement could be found with China on the boundary issue, neither Nehru nor any of the other Indian leaders pressed for it. Had that happened, India’s relations with China could have been remarkably different from what they are today.

This apart, Raghavan should be congratulated for a brilliant historical account of India’s strategy and foreign policy in the initial years after independence. This book is a must-read, and needs to be used as reference by those studying, teaching and writing on history.