Those of us who travelled on the railways in the 1950s and ’60s carry fond memories of those wonderful journeys. The romance of rail travel involves recalling puffing steam engines, soot in one’s hair, large tubs of ice in first-class compartments to cool temperatures in summer, the bustle of the platform, the call of the ‘chai walla’, luggage in steel trunks and the ubiquitous ‘hold-all’. Travelling on the narrow-gauge lines to the hills was another delight, vividly captured by Gurcharan Das in his introduction to this book, while describing the journey to Shimla and the hot breakfast at Barog.

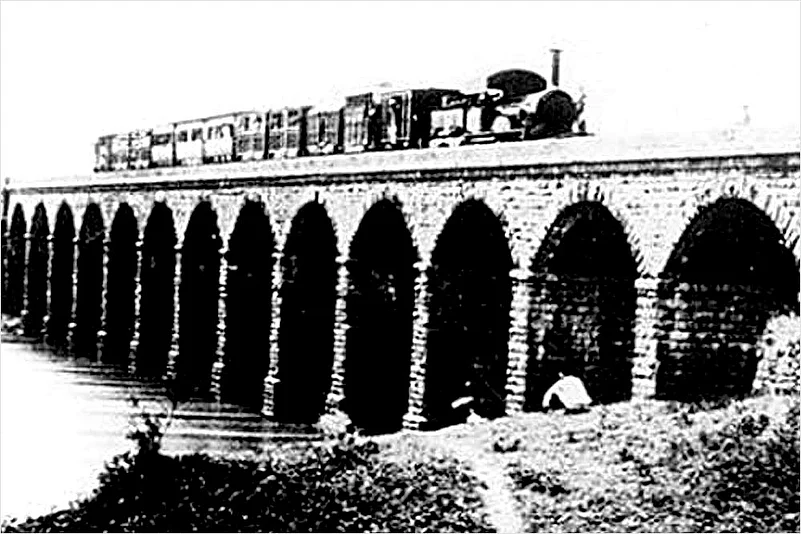

Bibek Debroy and his co-authors were part of a committee constituted to examine the restructuring of the railways. As preparatory work, the committee made an exhaustive study of the history of India’s railways, their growth and development. The enthralling subject is perhaps the motivation for this captivating book—an anecdotal account, with fascinating nuggets of information. For instance, official record says that our first railway was the train from Boribunder to Thane that ran on April 16, 1853. However, the authors narrate the story of an earlier construction, in 1837, when the Red Hill Railroad was built in the vicinity of Chintradripet in Madras, where a line was constructed for transporting granite for road construction. Initially designed for haulage by animals, locomotives appear to have been used later. Another early line was the one built for carrying material for the Solani viaduct as a part of the Ganges Canal construction near Roorkee.

Most early railways were built through private capital, with a return guaranteed by the government. This system was tweaked from time to time. In the 1870s, the government decided to enter the business of constructing and managing lines. In the 1880s, it began taking over the ownership of lines and left operations and management to private companies; in 1924, they took over that as well. These arrangements between the government and the firms were complex and ten different late 19th century formulations are mentioned. In the shaping of such a large network, individuals played an important role, like Lord Dalhousie, who decided on the gauge to adopt and lines to build; Rowland Macdonald Stephenson, who established the East Indian Railway and conceptualised a trans-continental railway; Col John Pitt Kennedy, who decided that the initial Calcutta to Delhi alignment should be via Rajmahal, recommended 12 principles for building railways in India and established the BB&CI (Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railway); Dwarkanath Tagore supported the rail link to the collieries of Raniganj and Treverdyn Rashleigh Wynne, a towering personality, built and managed the Bengal-Nagpur Railway.

No such book can be complete without a mention of steam engines. Around 14,400 of these black beauties were imported from Britain alone; a few of them, like Lord Falkland and the Fairy Queen are described. There are interesting tales about famous express trains of yesteryear—the GIPR Punjab Mail, BB&CI Frontier Mail, the Grand Trunk Express (between Peshawar and Mangalore), the Deccan Queen, the Flying Rani and the ‘Boat Mail’, from Madras Egmore to Dhanushkodi, which, alas, runs no more after an earthquake destroyed Dhanushkodi. Then there are Rudyard Kipling’s stories about the railways, crime and policing on rail, with a gripping story of the murder of a pay clerk on a train between Bombay and Manmad, and the building of the hill railways. The tapestry covers the period from the 1830s to Independence. Twentieth century developments include the creation of the Railway Board, the separation of the finances of the railways from general finances of the country in 1924 and snippets of the freedom struggle.

The raison d’etre for this series is the role of big business in the building of India. Are the railways big enough to merit a separate national annual budget? However, their contribution to industrialisation, though substantial, was not to the extent envisaged by Karl Marx. This was because of colonial policies that focussed on exports, securing the frontiers and rapid movement of troops where the need arose. Modern pundits say it didn’t reach its potential due to the small size of freight revenues, high elasticity of demand of freight services and low wages. However, the Railways did, and does still, play a crucial role in knitting together this diverse nation. This charming book is an essential read for all rail buffs.

(Vinoo N. Mathur is former member, Traffic, Railway Board, and president, Rail Enthusiasts Society)