Mahasweta Devi, who passed away this autumn, was a figure whose work can be seen as existing in and through multiple layers of translation. The first layer: she goes to the great terra incognita—adivasi India—and emerges with narratives of extraordinary power. These Bengali works get translated into English, books that influence literature and politics far away from Bengal. Genres shift: short stories get translated into plays. A Kanhailal Heisram picks up Draupadi for Manipuri theatre. Then a translation at a meta level: the ‘Mothers’ of Manipur re-enact its shattering climax—the naked confrontation of authority—as one of the most iconic images of protest in India, live political theatre. Scholars Gayatri Chakraborty Spivak and Samik Bandyopadhyay have both rendered her works in English. In a conversation moderated by Sunil Menon, they range across a wide turf—personal memory, history and translation—offering complementary readings, sliced through with a keen edge of contestation. Excerpts:

Gayatri Chakraborty Spivak: Samik, it was 1956 when we first met, remember? That’s 60 years!

Sunil Menon: That’s a good place to start this. Great pleasure to have you both here, talking about Mahasweta, and all trails leading from there. Politics, literature, language, translation. Encountering Mahasweta, reading her works, translating her works, reading her as a person, reading her politics, those would have been significant moments in your life in the world of letters. Could you take us through that journey?

GCS: I should turn to Samik. He introduced me to Mahasweta in 1979. He knew her long before I did. Perhaps he should begin.

Samik Bandyopadhyay: It’s a very interesting story, my coming to know Mahasweta. To be frank, even before I came to know her properly, I had developed a certain resistance to her. For very personal reasons. I knew Bijon Bhattacharya, her husband, a major figure in the Indian Peoples’ Theatre Association and New Indian Theatre...a great man and a great actor.

SM: Give us a sense of the time-frame....

SB: Nabanno, his masterwork, was in 1944. It was a landmark in the history of Indian theatre, a whole new handling of the real. I wouldn’t use the word realism: it was not realistic in the conventional sense, but responding to the reality of the famine of 1943-44, making a play out of that, with a conscious sense that it should take that reality to people in the city who were playing indifferent to it. Lots of people were coming and dying on the streets of Calcutta. Yet, things went on, as usual, the deaths didn’t seem to matter. The city was in denial mode. Not prepared to face its own guilt.

SM: Already, what we find in Mahasweta, a gulf between city and hinterland as different experience categories....

SB: Exactly. And Bijonda insisted there should be nobody acting in his play who comes from theatre as theatre. The practice of theatre was part of a large entertainment industry, already turning away from reality. He insisted on people who came with real-life experience. He would bring his long experience of travelling the villages of Bengal, living with them. And he was a fantastic singer and a lyricist in his own right. So bring all that experience into it, into the training of the actors. It wasn’t a conventional actor’s training. This was not Tripti Mitra or Shobha Sen, who he turned into actors. These were people dealing with the real in the raw.

SM: A certain analogy, then, to what Mahasweta does in fiction? Where exactly do you locate your problem....

SB: Well, Mahasweta marries Bijonda in 1946. He’s quite a colourful figure, I would say, at that point of time. And Nabanno had just exploded into something tremendous. She was just charmed by his personality, fell for him, fell in love with him and married him.

GCS: You know, Samik is talking about Bijon Bhattacharya’s extraordinary stature as a public figure. As a woman, I think one should also consider, if one is going to judge Mahasweta in terms of her relationship with Bijonda, that the word ‘colourful’ covers a multitudes of senses. I’m not going to say anything about it but, as a woman, I’d like to put this in here. Also, to your other question: no, Mahashweta was not doing that in her writing.... To an extent, a representation of the adivasis came from a different kind of novelistic influence on her. She herself has told me that she had been influenced by a lot of people, among them, for example, Howard Fast. So I’m saying one plus and one minus. One, you have to consider that explosive encounter not just from the point of view of Bijon Bhattacharya as an extraordinary public figure. And, I would insist, I don’t believe their artistic styles—or Bijon’s attempt to bring in the real and Mahasweta’s very sincere attempt to represent the tribals—are comparable.

SM: I meant at a very schematic level, taking something of the people ‘out there’ and turning it to raw material for art....

GCS: No, that relationship between adivasis and cities and so on, that was more—I don’t want to use an unnecessarily negative word—more of an accepted generalisation. See, my experience of that era did not touch my encounter with Mahasweta. I was born in Calcutta but my family is from Mymensingh. My mother in fact would go to Sealdah station every morning at 5 o’clock and sit there...as the refugees came. So when we also felt what Bijon Bhattacharya was doing had a real significance for people, even those from...you see, most Hindu Bengalis who came across from what is now Bangladesh, they all claimed to be zamindars. Mine was not a zamindar family. My father’s father was a landowner’s agent, he could not sit in the zamindar’s presence! That’s a kind of test Calcutta intellectuals are perhaps not capable of meeting. So I’m not speaking at all in a critical way about Bijonda as an extraordinary figure, but whatever resistance one might have to Mahasweta because of their relationship, I think there’s a huge area which must be acknowledged, but perhaps not spoken of, which relates to what we know: that for women even the personal is political.

SB: What I am saying really is, the marriage, right from the beginning, was a disappointment for Mahasweta. Bijonda gave up his newspaper job and became a whole-timer with the Communist Party. So there was poverty, there were problems, and Mahasweta was never used to that. She had had a very comfortable upbringing—a rich family, a very successful lawyer for a father. So she could not take this, accept this.

GCS: (Interjecting) But the more we go into this, that Mahasweta could not take poverty etc...I’m not going to speak about her private life, okay? I think if we’re talking about a person whose life we are here to celebrate, why one of us as a young person developed a resistance to Mahasweta is....

SB: No, no, no, I’d like to keep it minimal. Because there’s a point that grows out of that. So there’s an element of shock, of disappointment and the marriage breaks up. And that gives to Mahasweta, for the first time, a strong sense of independence when she comes away. At that point, there was nothing leftist, nothing in that direction...that develops later. There’s a gap, a long gap. Now, she has to make a very hard living after she leaves Bijonbabu. It is not comfortable. She enters into a relationship, which also doesn’t work, but these are immaterial. The thing of real significance happens around 1954-55....

SM: Is there a literary takeaway here?

SB: Yes, she had started writing already but in a very conventional Bengali women’s writing mode—that of Ashapurna Devi and others. She had had her reading of Tagore, but not much Tagore at that stage in her writing. More a very conscious women’s writing: there was a space in publishing for that, and a readership. She was entering that space as a writer.

GCS: What kinds of things are you talking about, what would be ‘women’s writing’?

SB: Two kinds of things, family life, the Ashapurna novel....

GCS: No, what titles? I’ve read most of them.

SB: Bioscoper Bakso, things like that, a lot of this highly romanticised stories of Vaishnava love....

GCS: Now, she herself considers that her life changed when she started writing Jhansi-r Rani. I think it would be a better idea to begin there.

SB: Exactly, that’s what I’m coming to. That’s why I was saying 1956 means a lot, historically very important. The country, newly independent, was preparing for the 1857 centenary. The state policy, that is, Nehru’s policy, was to claim or reclaim the 1857 experience from being described as the Sepoy Mutiny into the first Indian war of independence. That’s a very crucial political choice and decision. There was a large programme to bring in more research. S.N. Sen was commissioned to write a different kind of history...he framed it in terms of people’s uprising, local uprisings. That was immediately challenged by R.C. Majumdar. who read 1857 as a heroic revolt but one of the feudal class. Great work was happening...S.B. Chaudhuri wrote about the Santhal uprising, the tribal uprisings in eastern and central India extensively—pre-1857. Pratul Chandra Gupta specialised in the Marathi part of it—peasant revolts, tribal revolts in Maharashtra, Karnataka (which overlap quite a bit). Now, Mahasweta knew Pratul Gupta from a family connection...she decides to write about 1857 and also to bring in women into the 1857 frame. That was her choice, absolutely her choice. She goes to Pratul Gupta, who has access to all this material. And the story of the Jhansi experience, she was literally taught by him. That’s how she chooses the Rani of Jhansi as her subject. She studies laboriously all the archival material. She had the recorded history, archival history all in place. Then she decided, again on her own, that there must be a history behind these official, written accounts.

SM: That’s when she goes to the ground....

SB: Yes, she travels extensively all by herself through the territory the Rani was running through, chased by the British. From the Communist Party, there was also great work by P.C. Joshi, who was collecting the folk songs, tribal songs...these were already appearing in party newspapers, that kind of thing. So an interest in a parallel history, the history that grows in the people’s imagination, particularly if it’s a popular uprising.

GCS: A movement of subaltern cultural memory. That’s now very widespread—not just oral history, which is much more academic; not just testimony, which is much more academic...but this kind of competitive role of on-the-ground cultural memory confronting historiography, of which I think she was an early practitioner. And as Samik insists, she followed her nose. Today she would have a huge group theorising this way, that wasn’t the case then.

SB: That’s why I’m insisting all this was her choice: 1857, women in 1857, the cultural memory. This becomes her real entry into literature, the Rani of Jhansi. But then, I became very close to Bijonda and his son and, as an outsider, I started having a kind of resentment. How can somebody suddenly abandon this man, abandon her son....

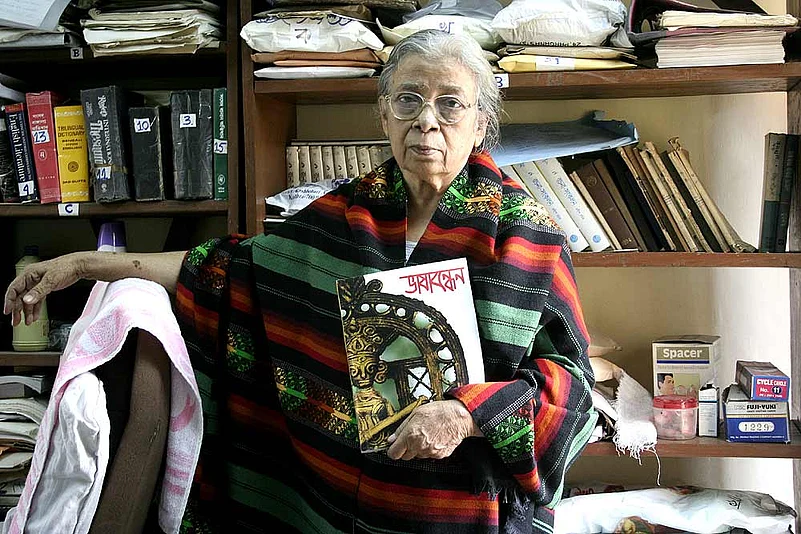

Scholars Samik Bandyopadhyay and Gayatri Chakraborty Spivak in conversation

GCS: (Protesting) Now, I just want to stop it here, because I cannot say in public why she left him. Not just because he was poor. As people who I hope believe in gender justice, we should turn the page and rather focus on Samik’s very well-informed insistence that this cultural memory initiative was her own. I think that’s where we should begin.

SB: One point here. Very few know about this, and I saw it happening before my eyes. When I really came to know her personally is 1973, when I start working with her on this textbook project. She spent four long years on it, working extremely hard. Oxford University Press was trying to create a body of textbooks for Bengali in English medium schools...they chose an English language teaching expert who had worked in Africa, assuming he had a readymade method. He had the honesty to tell OUP that his Bengali was not good enough, that he had the method but not the language. His wife happened to be a classmate of Mahasweta at Santiniketan. She suggested, why don’t you bring her in, she’s a writer in her own right. And Mahasweta took it as a cause...a mission. I, as editor at OUP, had to work very closely with her.

GCS: What textbooks were these?

SB: The Ananda Patha series. And I emphasise, these were for children alienated from Bengali culture....

GCS: Whose parents have chosen to alienate them....

SB: ...from the language. It had to be given to these children. But language is rooted in a culture, in practices, in different sorts of relationships, also across the rural-urban divide. Now, these city-bred brats had to be given awareness of the words, their meanings, ramifications. So that series brought her first real engagement with Bengali—a passionate, dedicated engagement.

GCS: I’ve been teaching at rural schools for 30 years and you have these textbooks. Clearly, someone went to Sussex to learn second language teaching. Excellent books, BUT, at the very bottom, they are not capable of using them. I told the ministry I could train the textbook writers, and I was told these texts were written to get English medium students—culturally estranged children—away from English medium. This is the real history of the education apartheid in India. When shall we stop focusing on the English language children? Believe me, this does not make me resent Mahasweta. It’s a problem within which we are all floundering, sinking and swimming.

SB: But this was a major thing for Mahasweta’s evolution as a writer. She was now reading contemporary literature seriously. Also the 14-17th century Mangal Kavyas, quite enamoured of that...works by Vaishnava proselytisers who were travelling and picking up words. If you read her pre-Ananda Patha works, the Bengali is extremely loose. But now emerges a different kind of Bengali, more layered, more shades coming in, a much richer Bengali that emerges only after the textbooks. That’s when she writes Hajar Churashir Ma.

SM: That’s also the time when Bengal is in ferment.

SB: At that point, she was not particularly engaged with the politics of the 1970s. No signs of that. These horrible things were happening. The Naxalite ‘actions’ were over...these actions against them, the massacres. We’re moving towards the Emergency. The general liberal political concerns we all shared. Nothing more than that. But that phrase, ‘the personal is political’, that was very true of her. Hajar Churashi is not so much about the Naxalites as about estrangement. Recently, someone said the Naxals came and asked her to write about them, they needed sympathy and therefore she wrote that story. Nonsense! Nothing of the sort happened. I certify, very strongly. Her own sense of estrangement from her son, the novelist Nabarun Bhattacharya, that was very strong then. She had also left her second husband. So, the loneliness. Hajar Churashi came out of that. When she was writing it, she had read out portions to me. When it comes out in 1974, it’s the Naxalites who complained! That it wrote about them, but didn’t really write about them.

The criticism prompts her to go back to the root of it, via Kumar Suresh Singh’s extensive anthropological studies, to the history, the tribal insurrections, to Birsa Munda. She travels extensively in Chhotanagpur with Singh. Then she writes Aranyer Adhikar, which was in style and method a mature return to her Jhansi mode. The remains of the history in the popular imagination. Also, studying the terrain itself, physicalising it. And her Bangla was now responding to the Mundari words...she made notes of them, I saw these...coining Bangla words to approximate that sound. When we worked on her translations, via her own draft translations, I often came upon words which were not Bangla. I asked her if these were Mundari words, and she said ‘I made it up’!

SM: (To GCS) In your foreword to the translations, you seem to cast a self-conscious eye on a kind of gap between academic feminism and the lived experience of women in the Third World. In her literary approximation to that subjectivity, how and where does Mahasweta close the gap?

GCS: Well, if you thought I speak of such a gap, I’d say that was not my intention. If you read that, then I no doubt made that mistake...but I don’t believe in anything called Third World women’s experience. The Third World as a phrase is used loosely to describe something that failed very quickly on the grounds of politics and nationalism. This is known, not just my opinion. So, no, I’m very critical of that phrase. And Third World women’s experience...there’s no such thing, it’s a really useless generalisation. As for academic feminism, some of it is very serious and careful. If I’d thought the academy was a place to denigrate, it would have been an act of bad faith on my part to have remained in it for so long. Then we should have burnt the universities!

SM: I mean, are those ‘authentic’ portrayals, or a fictional ledge from where she retrospectively analyses the mainstream?

GCS: I don’t believe the test of Mahasweta’s representation of certain kinds of characters is whether they are authentic or not. Authenticity is really not a criterion by which one judges literary production. I didn’t know anything about her at all when in 1979—because I’d heard she was an interesting writer—I turned to Samik and said, can you introduce me. I was like my first husband reading Othello for the first time when he was a graduate student! There’s a kind of advantage in that sort of ignorance; you encounter the fully-formed person.

Now, what I found—I said this to her right in the beginning, and she did not like me for it—I found Hajar Churashi too sentimental. I understand Samik is talking about her early work. I hadn’t read those (though I don’t think Ashapurna Devi is an author to be sniffed at) so I didn’t know that history. Nonetheless, I saw something in Hajar Churashi.

And I noticed, here were some literary representations of women in extreme situations. Whether third world or fifth world or ninth world I don’t care. I did not give to them a generalised expression and I certainly did not contrast them to academic feminism. Dominant feminism is something else...anti-intellectual and not at all afraid to insult someone whom they don’t know. Like the woman who came up to me in Bookworm, that old bookstore in Delhi, saying I am buying your translations but we don’t read your introduction! This kind of resentment, envy, in Bengali there’s a wonderful word, parasrikator, being struck by others’ grace. So I am not contrasting academic feminism.

What I was doing was looking at how much people of good faith within the academe, very serious feminists, could learn from this woman’s writing as she represented certain characters and contexts. Draupadi, Jashoda...I have not translated many things...Mary Oraon. Only those pieces where I felt this particular characteristic is demonstrated. I am not like an across-the-board translator of Mahasweta Devi.

SM: You treat these characters purely as...

GCS: I don’t treat them anyway! I am a translator. (Holding up her English translation of Jacques Derrida’s ‘Of Grammatology’) This is the fortieth anniversary edition. Translation is a curious thing. When you translate, you efface yourself, you surrender to the text. You do not represent it as anything, you let the text tell you how you should, with humility, describe what it’s up to. I try as hard as I can to write as if the text was directing me rather than me thinking something about the text.

SM: Fidelity....

Spivak: I did not speak about fidelity.

SM: ...and interpretive freedom, if you frame it in terms of those polarities that are nominally claimed to exist. How do you reconcile, like in the khayal tradition....

Spivak: Nayaki and gayaki.

SM: Yes...yet the word ‘khayal’ gestures at an interpretive terrain, as opposed to working with a bound text, as in Western music or Carnatic.

Spivak: No, no, that comparison between the so-called western interpretive act and freedom within the...you have to know a lot more about western music before you can say it is bound to something Bach wrote etc. It’s like saying anyone who plays Shakespeare is bound to Shakespeare’s texts. But within the structure of classical north Indian or Carnatic music—I told Edward Said this when he wanted to discuss music.... From the top at least—classical music is a from-above model—it’s a good model of democracy. That is to say, independent behaviour within a deliberately chosen set of structural rules. I think you should look at it like that than make generalisations.

Menon: But is there an analogy with translation?

Spivak: I think the verbal text is so different from an aural text, or a visual text, that it would be comparable only incredibly metaphorically and then you would create really such a loose metaphor that anybody who has actually translated word for word would find that analogy....

SM: Worthless, and why?

Spivak: Because the verbal word has a systematicity. Textuality, words...they start from nothing. Like when the child is learning in the mother’s arms or nanny’s arms. The weight we carry as human beings is words. And the articulations of differences between words that make meaning. There’s an extremely tight systematicity within which the unexpected emerges. Contingency emerges. Even such a line as ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’. Just that little difference between ‘gentle’ and ‘gently’, and an enormous explosion of contingency. Just as what the translator had ignored, between ‘stanadayini’ and ‘stannadayini’...an explosive difference in meaning. I’m not saying they are better or worse, just very different.

SM: This going out to the ‘adivasi’, from which the mainstream keeps a conscious distance. This idea of crossing, with ethnography, with language.... Varna society also had a benign fascination for the class they were subjugating, which fed into colonial ethnography. We always imply a gap, not zones of overlap.

GCS: I’m sure that’s a cultural idea, this gap. But I don’t think Mahasweta was trying to close it, except when she was talking to people in the city to do something to help these people. This I have seen, I was deeply involved there. She was focused—she and her ally, Gopiballabh Singh Deo—on seeing they were not oppressed and the law worked for them rather than against them.

SB: From the ’70s to the late ’80s, this was really her great phase as a writer. Then it tapers off, moves towards activism. The problem there was, she took great pride in not trying to understand the politics, the economics...sticking to a pure humanitarian frame. Advocacy. And it becomes simpler for the government to put her on committees, all that.

GCS: I’d say her literary representation of the tribals in general was less satisfactory. It was more what you call Orientalist...Noble Savage, with exceptions. Pterodactyl is about Chhattisgarh, most people would not recognise that unless they know Abujmarh. The rest of it is imaginary names, but Abujmarh....

SM: Famously, the place where the Indian state ceases to exist.

GCS: And she’s there. Trying to contest this entire superficial myth about what’s happening in those places. And she does it not by writing a confrontational political story. She writes for those who can read. The character of Shankar is not necessarily authentic. It doesn’t matter. A character like Othello is also not particularly authentic. I don’t think you’d find a Black guy like Othello walking the streets of Venice or wherever...where was it again?

SB: Venice.

GCS: Thank you. He was always the better scholar! So it’s not authenticity. She creates this character who says things, not things you hear authentically a tribal leader say. She makes everyone fail, and not do things. It’s a text written for those who know how to read. Marx had written that the revolution of the 19th century would take from the poetry of the future.... Pterodactyl is, to my mind, something political readers will see as poetry of the future in the future. For me, that one text is enough. When I teach, I keep modifying my translation. I tell students, I couldn’t quite get that and I’ll tell you the nature of the problem. Perhaps some of you will be moved to learn the language. That’s how I teach texts in translation—as inconvenient solutions. They translate Gramsci or Baudelaire through the English, even justify that, as my friend Ackbar Abbas does. There’s no respect for other languages, as if they are not mother tongues. As if one’s own mother tongue beats them all. So when you read it in my English, you’ll think of it as a convenience, whereas I think of it as the mark of a failure, always. Translation is necessary...and impossible. No language is translatable, yet we must always translate.

SB: I have a question...the way she treats history, she always says she has a great love of history, a dedication...but the mythification, I can’t conceptualise or theorise it.

GCS: It depends on whether she is doing it in fiction or in journalism. She certainly cared for dates and facts, never misrepresented them, but that’s an existentially impoverished account—history as a history of events. In terms of the historical, I don’t think she had a great deal sympathy for the kind of absolute impartiality that demands. I take that as part of what she was. Another great woman writer, the Algerian Assia Djebar (a great friend of mine, she dedicated her last novel to me and called me her twin sister)...she was so much the other way. She said to me when she was working on Carthage, ‘nobody is going to like this book because I like Polybius’. I like Polybius! One of her novels begins with the French guy in 1820 standing on top of the ship looking at Algiers and she’s trying to get into him and understand. Very militant woman she was. As for Mahasweta mythifying history...that’s what sent her to cultural memory in the beginning, because historiography was not sufficient.