Memoirs can often be an attempt to aggrandise incidents or to gloss over one's own failures and frailties of character. It is refreshing to come across a memoir that does away with all unnecessary embellishments and still manages to capture the essence of one individual's life and place it in perspective against the socio-political climate. A Memoir of Pre-Partition Punjab, Ruchi Ram Sahni (1863-1948) does just that. Neera Burra, Sahni's great grand-daughter who has edited the memoir, has succeeded in gathering the strewn threads of Sahni's eventful life from various sources and knitted them into a fascinating book that takes the reader into the political, social and religious churning of early 19th century colonial Punjab.

Ruchi Ram Sahni's autobiography, Self-Revelations of an Octogenarian, a title he acknowledges borrowing from R.L.P. Jack's The Confessions of an Octogenarian, unravels the twists and turns of his life as also in the history of a nation in a lucid narrative. It brings alive the life of an extraordinary man who was, in Burra’s words, “a scientist, educator, businessman, social reformer, politician and public intellectual”.

The book depicts the major milestones in Sahni's personal and public life—his schooling in the English education system, graduation from the Government College, Lahore, where he later became a professor of chemistry, his passion for scientific research and his religious inclinations. Though he finalised the manuscript in 1940, the memoir ends at 1919, shortly after the Jallianwala massacre. Nevertheless, it provides a rich source on a crucial phase in Punjab’s history.

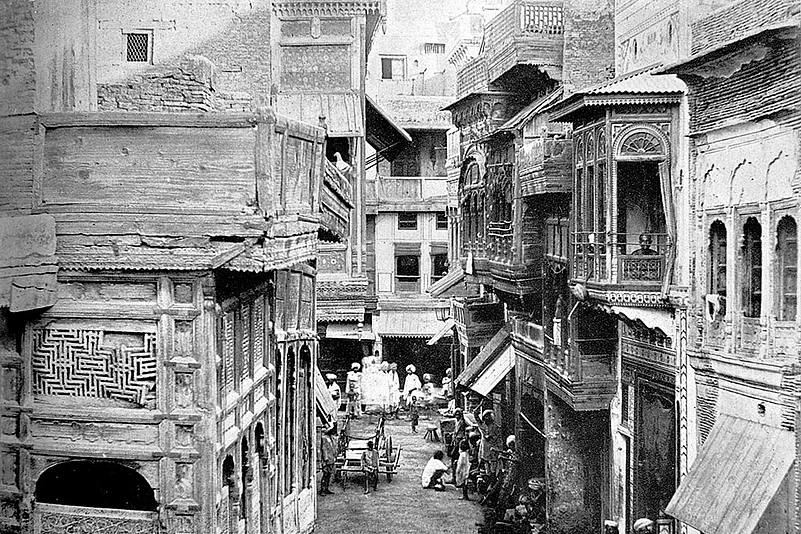

Burra’s compelling introduction reveals her dedicated perseverance in researching facets of Sahni’s life through family, libraries, newspapers and archival sources. Sahni comes alive in her introduction. His birth into a wealthy trader family in Dera Ismail Khan (now in Waziristan, Pakistan), the capsizing of their cargo ships, the consequent fall from affluence to want, are highlighted, as also its impact on the young Sahni. Those days gave him the first lesson in facing life’s travails. Forced to wear coarse cloth instead of silk, the boy went crying to his father, wanting to know if they were doomed to live in poverty. The father said, “Rochi Rama, badli aaye hai badli. Busle, busle, busle. Saade leere hi gille karenge, hor ki karenge?” (Rochi Rama, the clouds have come. Let them rain as much as they like. What else can they do except wet our clothes?). This became the tenet by which Sahni lived his life.

The memoir reveals Sahni as a torch-bearer on many burning issues—a man far ahead of his time in his thinking, who often challenged conformist ways and views of life. He was highly influenced by the Brahmo Samaj ideology, which posed a challenge to the orthodox Hindu belief system. This incurred the wrath of the Hindu religious establishment and he was ostracised by many of his students and colleagues. Even his mother refused to live with him or eat in his house in Lahore. He was also greatly influenced by Sikhism and the teachings of Guru Nanak.

A staunch adherent of issues like human rights, equality, widow remarriage, inter-caste marriage and franchise for women, Sahni vociferously aired his views against caste system, child marriage and dowry through his lectures and writings. He also took up cudgels against the oppressive colonial arrogance and discrimination of the British Raj and even renounced his title of Rai Sahib at the request of the Khilafat leaders. His strong views are evident here in the chapters The Ethics and Technique of Maintaining Self-Respect and The Indian Official's Trials and Tribulations.

Sahni became a member of the Punjab Legislative Council, but his memoir does not dwell much on his considerable contribution to public life. Neera Burra has commendably filled this gap by bringing to light many of his articles on various issues published in The Tribune.

Neera Burra’s laudable effort has given us a relevant source for understanding the forces that impacted the history of pre-Partition Punjab because it provides a view of that time from within the ring as well as a commentary from the sides. Sahni’s position as one of the first generation of Punjabis educated in English is equally important, as it is through the language of the coloniser that he chooses to express his reminiscences/experiences which abound with not just a critique of the racial discrimination meted out to Indians at the time but also the social movements dominant in pre-Partition Punjab.