The slice of sky I could see through the branches of the robust silk-cotton tree outside my cabin was being crisscrossed by relentless fighter jets that foggy February morning. The day before, Indian bombers pounded the Balakot terror-training camps to retaliate the Pulwama killings. Looking at the quaint shopping courtyard below, I wondered which payloads the fierce aircraft were carrying—Indian or Pakistani? From my office in the rundown urban village of Shahpur Jat—though technically very posh-sounding Panchsheel Park—I looked at the working-class people on their daily drudge. Do they care less about bombs from the sky?

The next TEL number was a collection of short stories by women writers from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The Pakistani narratives were truly an eye-opener. They were about body shaming, obnoxious patriarchal assertion, infidelity, workplace sexual exploitation, and sinister disappearance of men from a particular Islamic sect. Eminent Urdu writer Sheba Taraz’s story is a pointer to a significant dimension of Pakistani society. Flavouring her tale with Latin magic realism, she tells you about an outspoken woman who loathes sparing anyone. Being the source of discord in a milieu where menfolk are normatively listened to, her sharp tongue, when she chops it off, grows into a sprightly speaking tree!

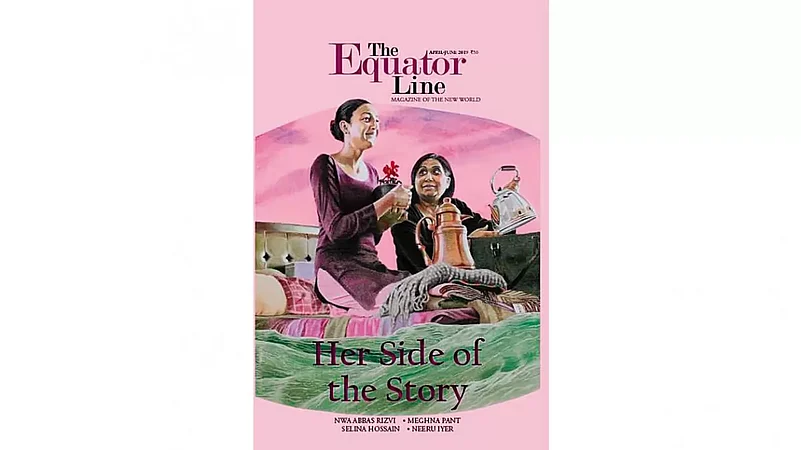

TEL, as The Equator Line was commonly known, was a themed, quarterly magazine of non-conformist writing. ‘‘This is like Cicero,’’ pointed out two German academics, dinner guests at home; I was thrilled, but it was early days. Though senior editors and designers worked for us, a handful of university students and young lecturers lent a hand too. The campus vibe around the office gave the magazine what kept it going—a ring of defiance. TEL never put business tycoons, cricketers or Bollywood stars on the cover. And definitely no politicians—Gandhi, Nehru and Mandela being the only exceptions. Every issue had a central theme and everything between the covers revolved around it. In one of the early numbers, ‘The Subcontinent: Reinterpreting the Radcliffe Line’, we revisited the clumsy, cynical Partition and its terrible consequences from either side of the fault line. Writers from India and Pakistan looked at different facets of life to report that despite four wars, terror and tension we have largely remained one whole culture.

An elderly man from Jaipur would visit our stall at New Delhi Book Fair every winter to renew his subscription. ‘‘The Granta of India,’’ he laughed, placing a hundred-rupee note on the counter. Unknowingly, the term caught on. With irregular ads but steady sales, and the generosity of some subscribers—a five-hundred-rupee cheque for an annual subscription—TEL survived. Until the Covid-19 pandemic ended our story. ‘‘Their struggle, visible all around the magazine, made it even more lively,’’ versatile writer Namita Gokhale remarked when a journalist asked her about TEL’s demise.

Reinforcing the liberal theme, we carried a series of sensitive, sibilant paintings by the talented young artist Dua Abbas Rizvi, Sheba’s daughter. I still remember two of them: a working-class woman in cheap chappals, coarse salwar-kameez, wrapped in a chador, walks down the road, looking at a seductive Eve beauty on the billboard above. The other one is of a liberated westernised young woman—in a BORN WILD tee and denim leggings, trendy sunglasses, her short hair coloured brown—turns her back on the framed picture of a bearded, turbaned mullah to catwalk on alluring pink carpet. Dua unerringly captures societal tension critiquing fundamentalism.

Unintendedly, we seemed to have discovered another Pakistan that has a disconnect with the world of hateful clerics treading on terror. In contrast, the writers and artists exalt a culture that is essentially middle-class, impacted by technology and globalised after the communications revolution.

But a society in transition challenges the entrenched retrograde forces by giving its women a new voice. Amina Yaqin, an academic in the UK, recorded the upheaval in her spunky essay, ‘Claiming Ownership of Her Body’. Assessing the impact of the annual Aurat March on International Women’s Day in her homeland, she recounts: ‘‘The event routinely evokes powerful emotions with the liberals endorsing it as a move against social stereotypes and the gatekeepers of women’s chastity disapproving of it.’’ Yaqin recalls a controversy about a March poster, a brilliant creation by illustrator Shehzil Malik that defies and challenges the straitjacketed patriarchy: Meri jism, meri marzi (My body, my choice). In 2019, some of the posters for the March 8 event indeed had the resonance of the age-old chains finally breaking:

Khana khud garm kar lo (Heat up your own food), and even more outrageous: Dick pics apne pas rakho (Don’t share your dick pics).

News of such quakes somehow does not cross the border to raise debates in the Indian media. Interestingly, Taha Kehar, a young writer in Karachi, was one of the finds of TEL. Among others, were Neeru Iyer, Ankita Anand and Manjari Singh.

One evening in his Pune home, former Times of India editor Dileep Padgaonkar read the entire TEL issue about the rich Indic heritage and wealth of classical texts, essential liberalism of ancient India. ‘‘The opening verses of the Rigveda do not preach any religion, nor do they threaten the infidel’’—the opening sentence of my editorial in that issue. Padgaonkar immediately wrote back:

Dear Bhaskar,

The most recent issue of your journal is a sheer delight. I read it from cover to cover in a single evening. Every page I turned heightened my interest. Just about every piece embarked me on a journey that opened vistas of knowledge, insight and wisdom. I cannot think of a sharper riposte to those who see to harness their shallow, voodoo version of Hinduism to promote their ideological and political agendas.

A while later, appreciation for this issue came from Nobel laureate Amartya Sen: ‘‘I celebrate your writing.’’

Bhaskar Roy is the founding Editor of the Equator Line

(The writer’s political memoir, Fifty Year Road, is slated to be published soon.)