In a bid to disentangle India from the diplomatic imbroglio involving Kashmir, India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, wrote to Sheikh Abdullah in 1952, insisting that Jammu and Kashmir’s newly formed constituent assembly affirm the state’s accession to India. In the same letter, Nehru implored Abdullah to eschew the question of sovereignty, as the people of Kashmir are not interested in such matters.

“An honest administration and cheap and adequate food is all that the simple-minded folk of Kashmir care for”, Nehru wrote. The issue of sovereignty continues to remain a central concern in the state, Nehru’s proclamation notwithstanding. In 1953, Abdullah was unceremoniously dismissed from his post, and his long-term acolyte, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, was entrusted by Nehru with the task of securing Kashmir for India.

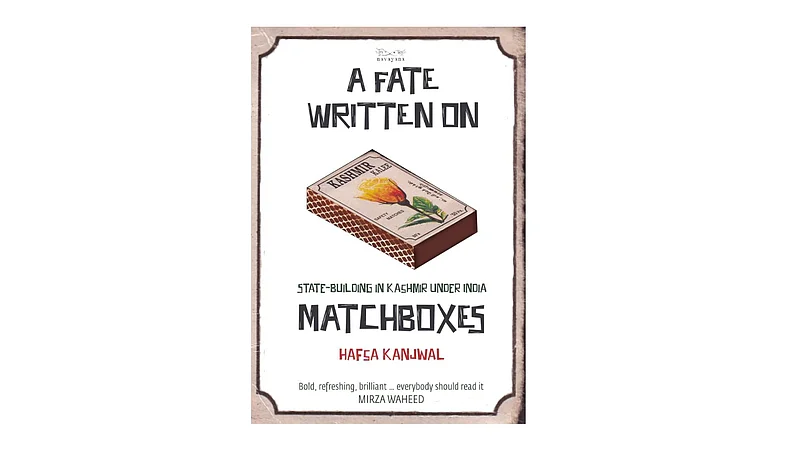

Bakshi’s governance regime was undergirded by the logic of territorial assimilation and emotional integration. In A Fate Written on Matchboxes: State-Building in Kashmir Under India, Kashmiri historian Hafsa Kanjwal historicises the state-building measures and procedures that served to entrench India’s sovereign assertion in Jammu and Kashmir following the accession.

Kanjwal argues that the compulsions of state-building stipulated that Bakshi implement several welfarist policies and make Kashmiris realise the tangible benefits accrued to them as a result of acceding to India, thus manufacturing consent for the accession. Drawing from extensive archival sources, bureaucratic documents, propaganda materials and oral interviews, Kanjwal persuasively demonstrates how Bakshi’s modalities of governance engendered new forms of domination and subjugation in Kashmir.

In his study of Occupied Palestinian Territories, Israeli political scientist Neve Gordon, through the use of the phrase “politics of life,” describes the manner in which Israel, following the June 1967 war, sought to consolidate its control. While brutally suppressing any form of resistance, Israel was equally preoccupied with improving certain aspects of Palestinian life in an attempt to normalise the occupation.

In 1968, Israel even assisted Palestinians in the Gaza Strip to plant six hundred thousand trees and helped improve agriculture by providing the farmers with improved varieties of seeds. This mode of control was rife with contradictions and eventually imploded with the breakout of the First Intifada in 1987. Borrowing from Gordon’s theoretical conceptualisation, Kanjwal brings to fore the myriad ways in which the Indian government and its “client regimes in Kashmir propagated development, empowerment, and progress to secure the well-being of Kashmir’s population” and make Indian rule palatable to the general population. In order to secure legitimacy for his rule, Bakshi deployed a strategy of “developmentalism.”

Both the Bakshi regime and the union government realised that “the only way the people of Kashmir could be kept under control was to provide the region with economic prosperity.” The union government generously opened its coffers to Bakshi on the condition that Kashmir’s ties with India be cemented permanently.

Bakshi's measures primarily benefited Kashmiri Muslims, who constituted an impoverished underclass. According to Kanjwal, the reasons behind it transcended parochial communal fealty. Kanjawal dispels the myth that the Muslim bureaucracy of the state was afflicted by communal bias and thus preferred to patronise their coreligionists only. The imperatives of state-building necessitated that sentiments of the demographic majority be swayed decisively in favour of India. The state administration could not afford a disgruntled Muslim population, particularly during the political turmoil that followed Sheikh Abdfullah’s arrest.

As is characteristic of client-patron arrangements, Bakshi’s largesse disproportionately extended to a narrow coterie of loyalists, garnering his government the moniker; Bakshi Brothers Corporation – BBC. Bakshi’s economic planning hinged on the Government of India’s liberal financial aid to the state. As Kanjawal notes, the grants-in-aid accounted for 30.7 percent of Jammu and Kashmir’s revenues, compared to 10 percent for other states.

From 1953 to 1963, the Kashmir government received approximately 15 million rupees in rice subsidies per year. Bakshi departed from Abdullah’s credo of austerity and self-sufficiency, adopting the “politics of abundance”. The reliance on federal subsidies not only dissuaded the state government from undertaking long-term investments in agriculture but also fostered dependency and ensnared Kashmir in India's politico-economic fold.

A significant section of the book deals with how the Bakshi administration fended off calls for a UN-mandated plebiscite in the region by courting Muslim-majority nations and communist bloc countries in order to secure India’s claim over Kashmir.

As the world was simmering in the Cold War, a two-day visit to Srinagar by Soviet leaders Nikola Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev in 1955 proved pivotal in emboldening India’s position in the United Nations on the matter of Kashmir. Also, Bakshi enthused the state tourism department with new vigour. The development of the tourism industry was intended not just to boost the state's finances, but also to legitimise Bakshi's leadership in the eyes of Indian and foreign media, as well as to foster integration with India's mainland.

According to the noted cultural theorist Homi K. Bhabha, nations are in a perpetual mode of creating themselves through narratives. National identity and cultural representations are intricately linked. Kanjwal offers rich insights into how the Indian film industry crafted a maximalist nationalist imagination of Kashmir as a veritable crowning glory in the Indian minds. Harnessing the picturesque backdrop of lush green meadows and snow-capped mountains, coupled with orientalist motifs of exotic and beguiling natives, Bollywood constructed Kashmir as a “territory of desire.”

Egged by the Kashmir government, film crews across India flocked to the valley in the 1950s and 1960s. The film industry delivered one blockbuster after the other like Kashmir ki Kali, Arzoo, Junglee, Janwar and Jab Jab Phool Khiley. While dealing with themes such as romance, pleasure, and the visual grandeur of the valley, these films portrayed Kashmir sans Kashmiris. These movies projected a harmonious relationship between Kashmir and India, unencumbered by political contestation. Additionally, the tourist propaganda booklets featured racialised and feminised characterisations of Kashmir. However, Kanjwal observes that such representations sparked discontent both in the public and within the local bureaucracy as well.

The “Politics of Life” also played out in equal measure in the domain of cultural production. With the creation of numerous cultural institutions, the government brought a vast amount of cultural production within its fold. The state administration monopolised cultural production by adopting a carrot-and-stick approach.

Bakshi cultivated a pliant intelligentsia by patronising poets and artists who trumpeted the government's narrative of peace and progress while marginalising those who did not parrot the government propaganda. The likes of Rahman Rahi and Akhtar Mohiuddin waged a prolonged literary protest against the excesses of the Bakshi regime, thus frustrating its efforts at assimilating “the cultural intelligentsia into the state-building project.”

Reliance on “Politics of Life” as a governance strategy does not entail renouncing repressive measures of control. The final section of the book illuminates the harsh, repressive measures undertaken by the state government to quell political dissent. Apart from extensive surveillance of the media, the government deployed civilian militia, ironically named Peace Brigades, to clamp down on any whimper of protest. The local state was at the forefront of repression against those individuals and organisations that expressed misgivings about the government’s stance on the political status of Kashmir.

Bakshi’s rule was ridden with rampant corruption and authoritarian abuses. The government of India eventually ran out of patience with Bakshi and, in the summer of 1963, asked him to relinquish office. A few months later, the breakout of “Moi-e-Muqaddas” (holy relic) agitation throughout the state exposed the chinks in the armour of “politics of life”, laying bare its tenuous nature.

A key takeaway from the book is the striking repetition of the different modalities of control used by the Indian government in the region over seven decades. In the longue durée of Indian rule in Kashmir, the recent intensification of authoritarianism is hardly a novel phenomenon; it merely represents the latest iteration of previous policies.

The book challenges the conventional account of the triumphalism of Indian democracy and sheds light on the aspects often neglected in the scholarship. Kanjwal’s ability to weave diverse sources into a compelling narrative brings to life the complexities and contradictions of state-building in Kashmir. The author’s painstaking research and meticulous attention to detail make this book indispensable to the study of Kashmir’s modern history.

Raheel Bashir is a PhD Candidate at Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University