Writing about this attack while living in Bangladesh puts one in a rather difficult position. My country’s abysmal track record of protecting writers and publishers from similar attacks in the past has pushed us down a slippery slope, where writers and journalists live in an atmosphere of fear and choose to self-censor rather than speak their minds. That’s precisely why there is an ambience of total silence over the despicable attack on Salman Rushdie in the Bangladeshi media. Only news items were published on the front or back pages immediately after the attack. Rushdie then vanished from print editions altogether, and was sent to the section marked “international” or “world” in online editions. Only one English daily carried an op-ed on the subject and that piece, a reprint of a Conversation UK article, is written by a UK-based, non-Bangladeshi literary researcher.

Taslima Nasrin was forced out of the country in 1994 upon publication of her third novel, Lajja (Shame). She has since lived in exile. Prolific writer Humayun Azad was brutally attacked in 2003 by members of Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh after he published his novel, Pak Saar Jamin Saad Bad, which was an allegorical depiction of how Jamaat-e-Islami, one of the main parties in the BNP-led coalition then in power, had collaborated with Pakistan’s occupation army in killing Hindus and freedom fighters in 1971. He died the next year. The verdict on the Azad murder case was delivered by a Dhaka court in April this year, 18 long years after the attack.

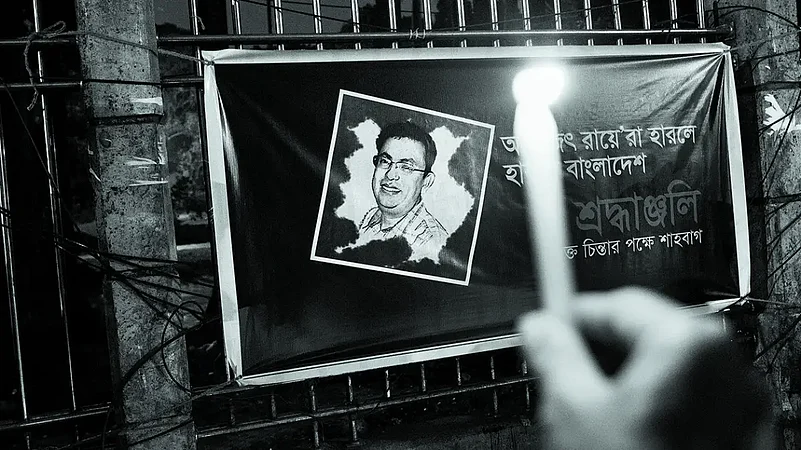

Then again, from 2013 on, several secular writers, bloggers and publishers (including Ahmed Rajib Haider, Avijit Roy, Ananta Bijoy Das, Washiqur Rahman, Niloy Chatterjee, Faisal Arefin Dipan and Ahmedur Rashid Chowdhury) were attacked, execution-style, with machetes. Only one of them, Chowdhury, survived. Most of the cases filed over these attacks are still pending.

Therefore, on the one hand, threats of militant attacks are very much alive and kicking, and on the other, there is fear of legal repercussions. Because, due to the enactment of the Digital Security Act, if anybody feels that their religious feeling is hurt over any article or item published online, no matter how absurd that feeling might be, they can file a case against the writer or the newspaper editor.

Faced with such a fear-mongering climate, when you sit down to write an article unequivocally condemning the attack on Rushdie and the ideology that birthed the attacker, you ask yourself: in this situation, what’s the limit of the thinkable for someone living in Bangladesh, especially when talking about Rushdie vis-à-vis The Satanic Verses, which appears even more incendiary today than it was 30 years ago?

No matter how much the space for debate has shrunk, we owe it to every writer who has ever been attacked for their words—whether in the US or Russia or China or India or Bangladesh—that we continue their fight by giving robust expressions to our own thoughts. More so for Rushdie, who is the meteor in our imagination, having touched so many lives and jolted so many readers into questioning their perceptions.

In the early 1990s, when I was stepping into my early teens, my hometown Bagerhat scarcely had any reader of a classic English novel in its original format, let alone a contemporary novel as complex as Verses. A large body of Russian, North American, French and English novels had a considerable readership, but all those books were read in Bengali translations. Yet, the mainstream Bangla dailies conveyed to us news of violent protests over the book and of course, the fatwa, thus taking the waves of the Rushdie debate to the country’s south-western corner. As the book was banned immediately in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, our interest in it naturally grew.

The leftist circles that I had started hanging out with comprised of youths who spoke for Rushdie’s right to exercise critical thinking. Unlike today’s Bangladesh, the leftist student parties had considerable sway over students back then. One reason was that the 1990 mass movement, which had brought down General H.M. Ershad’s nine-year-long autocratic rule, was jointly engineered by student fronts of all major political parties, barring the religiously oriented ones. The spirit of the movement created an atmosphere for critical thinking and ideas to grow and flow among the youth. After Ershad’s fall, the BNP, the party sympathetic to majoritarian religious narratives, came to power. It banned Taslima’s Lajja in 1993 and Azad’s feminist essay collection Nari in 1995. Yet, members of its student front in Bagerhat, who had rented a two-room office in my neighbourhood, would hang out with activists from their own party as well as those from the leftist parties and the Chhatra League, the student front of the BNP’s arch-rival, the Bangladesh Awami League.

Having weaned off fairy tales and children’s thrillers, I was reading, on the one hand, detective thrillers and abridged Bengali translations of European classics (published by Sheba Prakashani) and on the other, all those Bengali translations under the rubric of “Marxism” published by Russia-affiliated Pragati Prakashani. I was always around the BNP office or tea stalls adjacent to it, so that I could share my ideas or perhaps get new perspectives from seniors, many of whom were avid readers and not politically active any more. Verses, Lajja and Nari were at the centre of many long discussions. There also were talks on Syed Shamsul Haq’s Khelaram Khele Ja and Azad’s Sob Kichu Bhenge Pore, both of which rather openly deal with issues of sexuality, including graphic description of sexual encounters between men and women. When the Awami League, the party that promoted the spirit of the 1971 Liberation War and non-communalism, came to power in 1996, this atmosphere of openness was given a further boost and our debates would also include books by Ahmed Sharif and Aroj Ali Matubbor, both of whom question Islam, Christianity and Hinduism from scientific and humanist viewpoints.

The most interesting bit about those days was that back then, I could talk about a lot of subjects from science to religion and sex with friends and seniors, irrespective of their ideological leanings. True, I faced vehement opposition in many cases, but that only led to more impassioned arguments. The leftist circles are there, though to a much lesser extent. The friends and seniors with whom I had those debates are also there, but the cultural licence to initiate such debates seems to have expired long ago.

By the time I laid my hands on The Satanic Verses, towards the late 2010s, I had already read Rushdie’s essay collection Imaginary Homelands and his second novel, Midnight’s Children. I had not expected the world’s most famous English-language author to write such fine literary criticism. His critical perspective in every piece is authentic and his language extremely lucid. His resistance to Western literary and artistic discourses impressed me the most. As for his magnum opus, Midnight’s Children, it seemed like an explosion of creativity holding answers to all my questions about language, politics, history and storytelling in fiction. It defies modern European traditions, but combines history and myth, post-modernism and magic realism, to create an epic that has significantly broadened the horizons of fiction in general and South Asian fiction in particular. The “chutnification” of English also happens here, most remarkably. I especially noticed Adam Aziz’s shift from a believer to a non-believer, and the way his son Salim Sinai, the protagonist, hears a voice calling to him, which Salim compares for a few fleeting moments to Prophet Muhammad hearing the voice of Allah.

The taste of Children’s “chutnified” language made it easy to dive into Verses, in which the innovative use of language has been taken several notches higher. In the realm of ideas, what struck me first are questions surrounding atheism and parallels between our time and that of the 7th century, which had featured as seeds in Children and had grown up as enormous trees with airy roots in Verses. Maybe it was due to my upbringing and the cultural climate I was exposed to, but I could never, and still don’t, see any problem with a writer raising questions about any aspect of a religion, as long as those questions are well-founded and nuanced, and not tainted by prejudices of any kind.

Fitted in a post-modern narrative, it’s a formidable magic realist tale about two Indian men, Gibreel Farista, an unsuccessful Indian film actor, and Saladin Chamcha. They jump from a hijacked plane and like meteors, land on the shores of England, where they embark upon many adventures (or misadventures). Farista, who hears voices in his head, is prone to dreaming elaborate dreams in which he imagines himself as the archangel Jibreel, and sees visions of 7th century Arab societies that relate directly or indirectly to Islam’s Prophet Muhammad.

These dream sequences, of which there are several—the two most notable appearing in chapters titled “Mahound” and “Return to Jahilia”—are the reason why he is accused of insulting Islam, not only by Muslims but also by some acclaimed writers, including John Le Carre, Roald Dahl, Zoe Heller and Pankaj Mishra. But is there an authorial intention through which we can work out an illuminating interpretation of these dreams? Although Rushdie’s unreliable narrator—who is poking fun at everything, including his own comments, and is critical of every religion—makes it difficult to work out any consistent authorial intent, plenty of clues are given in different chapters, especially in the one titled “A City Visible But Unseen”, where Farista repeatedly expresses his wish to turn London, a city in transition, into something different. The wish derives from his disillusionment with London, of course, but also underlines the painful process of a migrant’s transformation, which, among other things, reflects the migrant’s experience of being Othered. That’s why, in his sane or insane state of mind, subconsciously or unconsciously, he is looking for models of a transitional city in ancient Arabian societies to which his religious roots are attached. But that’s just one interpretation.

Supported by Rushdie’s own comments in his autobiography Joseph Anton—I’m of the opinion that in addition to exploring themes of identity and transformation, he consciously presents readers with a materialist interpretation of the advent of Islam in Arabian societies. I’m also of the opinion that these dreams defy their assigned roles in the narrative and assume a character of their own, and this is also part of Rushdie’s authorial intent.

As I read and reread the dreams, I felt Rushdie’s portrayal of Islam lacks originality and blandly echoes prejudiced Westernised notions of Islam. His materialism, which I found to be selective, does not give us the whole picture. He explores the perspectives of many characters, from renegade Salman to blasphemous poet Baal, but the only perspective that remains unexplored is that of the Prophet’s. Nevertheless, Rushdie’s portrayal is way more nuanced and clever than Azad’s Shubhobroto O Tar Somporkito Shusamachar, in which Azad, much like the director of Innocence of Muslims (Nakoula Basseley Nakoula, Egypt), has depicted the Prophet as one whose passion lies in destroying temples.

So I loved Farista and Chamcha’s misadventures in London, but found the dream sequences to be blinkered. I found Azad’s Shubhobroto and the short film Innocence to be driven by propaganda fed by Western discourses on Prophet Muhammad, which also find parallels in the Hindutva version of Islam and the Prophet.

Now, the question is: so what? Even if I dismissed Rushdie’s interpretation of Islam, like I did of Azad, so what? No criticism or dismissal can strip Rushdie or Azad of their right to express what they think about life, politics and religion. No criticism justifies the violent reactions to Verses or its author. In their violent outbursts, a vast majority of Muslims conflate Rushdie, as well as the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten and the French magazine Charlie Hebdo—both of which printed cartoons of Prophet Muhammad—with the West. What Rushdie did in Verses is a worthy attempt at a creative exercise, whereas what those newspapers did, as observed by Megan Gibson in Time, was a calculated move to boost circulation. One may disagree with both Rushdie and those newspapers. But why react to the book or the cartoons in this childish way? Why show paranoia over the representation of the Prophet? Why always choose violence? And how does it prove Islam to be a religion of peace? If one really thinks this is worth fighting, why is it not possible to fight it artistically or journalistically? Why this blind determination to confirm the Western projection that Muslims are a homogenous entity devoid of the power to think?

Looking at violent outbursts over Rushdie’s book, five Muslim scholars and writers (Edward Said, Aga Shahid Ali, Eqbal Ahmad, Ibrahim Abu-Lughod and Akeel Bilgrami) sent the following letter to a 1989 issue of The New York Review of Books:

“As writers and scholars from the Islamic world, we are appalled by the vilification, book banning and threats of physical violence against Salman Rushdie, the gifted author of Midnight’s Children, Shame and The Satanic Verses. This campaign is done in the name of Islam, although none of it does Islam any credit. Certainly, Muslims and others are entitled to protest against The Satanic Verses if they feel the novel offends their religion, and cultural sensibilities. But to carry protest and debate into the realm of bigoted violence is in fact antithetical to Islamic traditions of learning and tolerance.”

When bigotry is on the rise all over the world and across religions, we must respond by writing more boldly for artistic and journalistic freedom. As for Rushdie and those attacked in Bangladesh, we must do more through writing and activism to keep our secular traditions alive.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Meteor In Our Imagination")

(Views expressed are personal)

Rifat Munim is a Dhaka-based editor, writer and translator