The Spy is based on Mata Hari’s tragic story, beautifully woven in her own words, of a woman who dared to defy the hidebound conventions of a century back and paid for it with facing a firing squad in a French prison. Coelho has painted a sympathetic picture of a vulnerable tragic figure, which still mystifies the world.

Paulo Coelho, the Brazilian author, is an international phenomenon whose books have been most widely translated and sold worldwide. His readers include the former US President Bill Clinton. Belonging to the generation of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, Coelho has been a non-conformist, living life on the edge. His books have been inspired mainly by his own life.

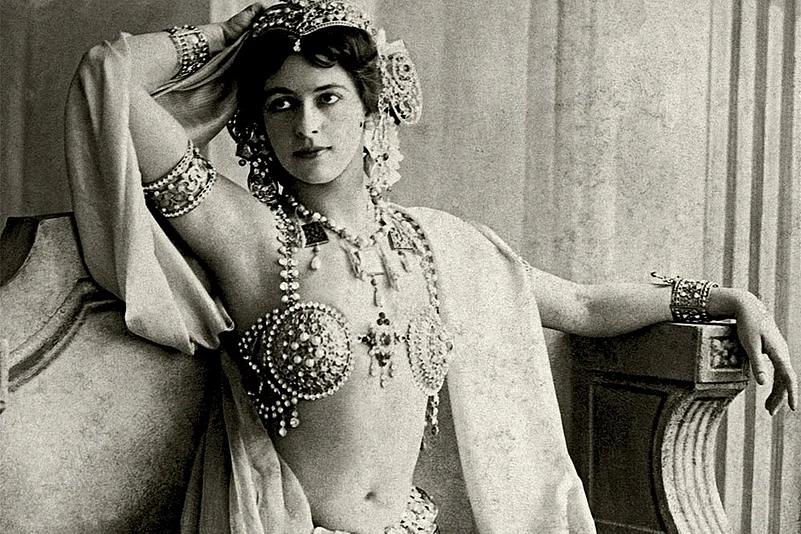

The story begins with an innocent Dutch girl, Margaratha Zelle, named after a famous dancer, who marries an officer of the Dutch Army but comes into her own as Mata Hari, who dances her way into the hearts of Paris despite being desperately poor when she arrives in the city. As Coelho says in one of his earlier works, “you don’t choose your life, it chooses you”. Mata Hari dreams and lives life abundantly. But life was not always a bed of roses for her. She was raped by her school principal when she was sixteen, and raped and abused by her husband who took pleasure in re-enacting the scene.

In Oscar Wilde’s words, Mata Hari was “the nightingale who gave everything for love and died while doing so”. But not before she had charmed and seduced the major concert halls and salons of Paris. In course of time, she made friends in the highest places, including ministers and the president of France. Pablo Picasso yearned to sleep with her.

Mata Hari’s greatest sin was that she had a mind of her own; like the Greek princess Psyche, she was too independent. Even as her beauty faded with age and her fame declined, the Great War intervened, making her a plaything for the great powers—Germany and France. As Coelho says, “The first casualty in war is dignity”. Recruited by the Germans with the code name “H21”, sounding like “a seat number on a train”, Mata Hari found the whole business of intelligence a ridiculous game. Yet she offered herself to the counter-intelligence service of her beloved France, only to be accused of espionage in the paranoid wartime atmosphere.

The French, who pride themselves on its legal system, found Mata Hari’s trial an aberration of justice during the war. The French counter-intelligence could find nothing incriminating against her, but all they needed was a convenient scapegoat. As the Ecclesiastes says, “Instead of justice there was wickedness; instead of righteousness there was still more wickedness”. As her lawyer contemplating her trial says, “The evidence against Mata Hari was so poor that it was not fit to punish a cat”. She may have been a liar and a prostitute, but Mata Hari was never a spy.

Life made Mata Hari go through so much in so little time. An optimistic woman whom time had left bitter, lonely and sad. The courageous and fearless woman paid the price that she was destined to. In the end, she did not need to fight anymore. Even as a prisoner, her spirit remained undiminished. Yet, when death came, she was ready for it, dignified till the bitter, unjust end. She faced the firing squad impassively. One of the soldiers who fired at her fainted even as Mata Hari collapsed.

Mata Hari’s story, intertwining the two oldest professions, still retains its mystique—it has spawned volumes of fiction, non-fiction and a celebrated Hollywood biopic. Women have been employed by intelligence agencies since time immemorial. During the Cold War, the CIA frequently resorted to ‘honey traps’ to neutralise the Soviet ‘swallows’ notorious for seducing foreign diplomats. Indians going on a posting to Moscow then were given special security briefing so that they did not fall prey to the artful fair sex. But none would have been like the inimitable Mata Hari.

(The writer is the former chief of R&AW)