He looked distinctly out of place in that Emergency Ward, smartly dressed as always in shades of beige and brown, in only the finest – from his suit and tie to his polished-to-a-shine shoes. Only that thing around his neck did not belong to my brother; a ghastly green plastic rope, sawed off shabbily at the ends when they brought him down. That and his face, eyes bulging, tongue out and mottled. I did not know how to respond. How does one respond to something like that?

Instead, I went about dusting his suit and rearranging his arm, which was dangling at an odd angle from the stretcher. The doctors declared him ‘dead on arrival’.

I could deal with an arm dropped off a stretcher. But when they returned him from the mortuary, they had wrapped him up in sheets and tied him up with ropes.

Did Arijit Lahiri, beloved brother, think of what was to come when he made his decision? Did he know his clothes would be torn off him and his insides poked at by strangers? Did he think about it as he went about organizing the day? When the body is finally consumed by fire, all that you have left are questions.

We rehearsed his last day incessantly, picking over it for clues. We heard he walked the dogs, whom he adored, then gulped down his breakfast and drove off, cheerfully fixing to meet his wife and her parents for lunch. From colleagues’ accounts, we heard it had been another hard day at the office. He had his usual simple lunch of daal and sabzi and then drove out. After office, he had made a detour to the market. He stopped to buy the plastic rope he needed and then went on to hang himself from the ceiling fan, in the old house he had lived in, before moving to a more fashionable gated community. His laptop and briefcase were placed neatly on a chair. His wife found him that evening in their erstwhile home.

In retrospect, I was relieved when we took him home that last time, I in the front of the van, him, draped in sheets, at the back. The driver played the radio and I began to accept that it was all over. We were alone then, he and I, not laughing about some silly joke or quarrelling even, just silent. My questions to him began in that moment and I have never stopped asking. Okay, we’d had it tough, he and I. But Arijit, you’re supposed to fight, right? You’re not supposed to cop out? He didn’t answer. Maybe dead people laugh and the living can’t hear them. I would like to believe that he was laughing, showing his tormentors the finger as we trundled over the potholes and made our way home. His home. The keening of the dogs brought the first rush of tears to my eyes. Kit Kat and Nutty knew what took me 24 hours to realize. That he was gone.

He was a few years shy of his fiftieth birthday. That year he hadn’t come home that year for rakhee (Should I have guessed?) and the last time we spoke he had said we would meet and talk about things that were not going so well in his life. (Should I have insisted he come over immediately?) Over the years, we had grown apart, busy with our own lives and work (Should I not have found time for him?), but he called, usually on his way to office. I invariably told him to drive carefully; he would laugh and continue chatting: about Ma or Arjun, my son and his favourite nephew or his dogs and mine. I’ll always think of him like that: a whiff of expensive aftershave, Rayban glares and blaring music as he drove off, hand raised in a quasi-salute. There was no note. No accusations. No remonstrations. The ringtone on his phone played his favourite Hindi film song from Dil Apna aur Preet Parai (1960) ‘Ajeeb daastaan hai yeh, kahaan shuroo, kahaan khatam…’

I re-examined the lyrics of the song, wondering if there was a hint there that I had missed. In the clarity of my head I know I am not to blame. In the dark recesses of my heart, guilt seems to have found a home.

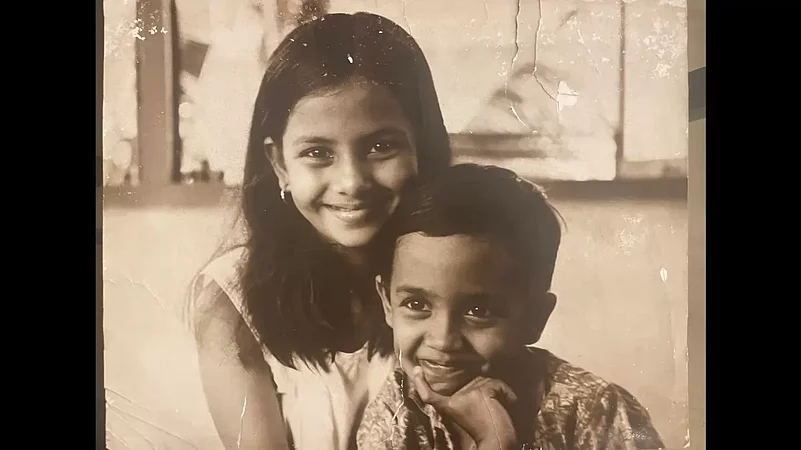

As a young boy he loved the cinema and when Baba took him to see Battle of the Bulge, he was sleepless with excitement. We lived in a modest flat in Union Park, Bandra, Bombay and the imagined roar of battle filled the rooms for days. Our games were mostly play-acting and improvising, because we did not have too many toys. So a ruler would double up as a gun and a dining chair as a war tank when we played war. Then, he saw Bramhachari with a visiting uncle and lost his heart to the Good Samaritan Shammi Kapoor for a long while. He tried to hide his tears when he narrated the story to our help, Gyanada, whom he adored. I teased him and that made him very angry. Ma and Baba took his side invariably, and that made me angry.

My parents absolutely adored their son and I often felt ignored in those early years. Left out of their games and treats. I have often thought that it was the divorce our parents went through that left him off-centre. He couldn’t cope with the absence of our father and showed his resentment in many innovative ways. It was even more awkward when my mother remarried and found happiness with our stepfather. We reacted in our own ways, I was delighted to meet Bapi and happily learned to consult him on every little matter. My brother was wary, diffident. Things got better when our little brother Shamya was born because we both loved him unequivocally. Arijit accused me of loving the new entrant a little more and that was partly true.As the older sister my attention and love transferred to this curly-haired baby who became the centre of my universe. If Arijit felt betrayed, I was guilty.

My brother ended up playing serious cricket for the State’s Under-19 Team and was a good student at St Xavier’s College. Shamya hero-worshipped him and for a long period of time went to school with the Under-19 Cricket Team’s cap hidden in his school bag,to show off to his classmates. I got married and moved away from home, to live in another city.

What causes depression? Many tiny moments of sadness or one traumatic legacy that sweeps you in a storm you never recover from? And what is the tipping point? When does the burden become so great that it makes someone who is depressed take their own life?

For months afterwards, friends and family who had seen him grow up were shocked that Arijit could take his own life. In the family, he was known, after all, for his dry, deadpan sense of humour that spared no one. When he held forth, we cracked up.

Was he trying to lighten Ma’s mood that last time he called hours before he died? All she could say, disbelievingly, when she heard the news was that he seemed to be in such a jovial mood that morning, teasing her and joking about relocating to Kolkata to take on a job that meant less pressure, even if it meant opening a kirana dukan (a grocery store) in Jodhpur Park where she lived.

We looked for answers elsewhere since there was no letter to explain the cause. The doctors said he was ‘clinically depressed’ and that this was probably caused by the brain haemorrhage he had suffered some years earlier. Others said it was office politics that left him feeling defeated. Yet others spoke of the difficult situation at home. But there didn’t seem to be much more than any man in his late forties faces. And even as I think this, a fresh feeling of guilt. Who am I to judge what a man can bear or what he cannot?

Just a few months earlier, when my son was visiting from London, Arijit had taken him out for a spin and made plans to see him soon. ‘Just us,’ he had said, winking conspiratorially. ‘We’ll have a blast!’

Seven years have passed by but closure still evades us. We repeat those questions in our heads and still search for some sliver of an answer. In vain.

On the March 7, now we remember him in our own ways and, fittingly, there is complete irreverence in the homage we pay him. I think of the man who often said, ‘I am too old for Rock ‘n’ Roll and too young to die.’

I recall that time, for instance, when our parents had gone to Europe and wehad the run of the flat for a fortnight. I was at home, reading, when a very harried and hassled Arijit came rushing in, completely out of breath. It seems he was learning how to ride a motorbike when it rammed straight into a police van! Flustered and nervous, he had invited the cops to our flat with the offer of tea and omelettes if they let him off.The police did let him off with a reprimand but he never practiced riding the motorbike in Jodhpur Park, again!

Two night-time stories that come back sometimes as shadowsgather and regrets return. The first is being woken up from a dead sleep, a sleep of emotional exhaustion brought on by the intense and solemn memorial service we had organized for my stepfather’s first anniversary. Shamya’s wife Ajitha is shaking my arm.

“What is it?” I ask.

“I don’t want to frighten you but Dada has set the bed on fire.”

Of course, he was penitent. He shouldn’t have been smoking in the first place. He shouldn’t have been smoking in bed.

“Do you want to kill yourself?” I asked.

He paused for a second, with a comic’s timing and then guessing perhaps that it was not the time for a smart answer, said, “No.”

(What would his real answer have been?)

The second: It’s night, a cold night. We are all snuggled down and enjoying the warmth of our blankets, enjoying that rare thing: a winter night in Bombay. I must have been ten and Arijit six. Outside we hear a beggar calling for alms, bemoaning his fate at the night and the cold. I am about to duck my head under the pillow and cut him out when Arijit gets up and rushes to the window, bearing his blanket aloft. He throws open the window and calls to the beggar. “Dada, yeh lena,” he shouts and the blanket flies out into the night, a harbinger of hope.

I wonder sometimes whether all Arijit needed was someone to open a window somewhere and throw him a blanket.

(Was that someone supposed to be me?)

Sleep well, little brother.

Excerpted from 'A Book of Light', edited by Jerry Pinto