“…from December 16th, the dadiyan, maa and sisters of Shaheen Bagh had landed on the streets. Against atrocities, against this law, and forced to protest on the road to save their country from breaking up. I was also a part of Shaheen Bagh’s protest. Like me, Shaheen Bagh and the mothers of India were in the same mind that how to save their children’s from a law like NPR and NRC.”

This is an excerpt from a letter Nasreen wrote to her three kids, explaining the events that led to the historic Shaheen Bagh protests. It alludes to the night of December 15, 2019, when Delhi Police barged into Jamia Millia Islamia and used tear gas and batons, and allegedly even bullets, on students during an ongoing protest against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and National Register of Citizens (NRC). Muslim residents of the neighbourhood—already worried over the possibility of themselves or their loved ones landing in detention camps—were aghast that the protectors of law had wielded their batons on students, who felt like their own. By December 16, the collective pain and anger spurred a momentous sit-in protests 3.5 km away from the university campus, led by ordinary women sloganeering in extreme winter, who managed to block an arterial road for 101 days, till—not the law, police or politicians—the nationwide Covid lockdown compelled them to abruptly end their fight to revoke the contentious laws.

Nasreen’s poignant handwritten letter in Urdu can be found at the heart of Har Shaam Shaheen Bagh (Every Evening Belongs to Shaheen Bagh), a book by Prarthna Singh, a photographer and visual artist from Mumbai. Singh started documenting the revolution from its nascent stage, using her nani’s house in Sarita Vihar, a stone’s throw away from Shaheen Bagh, as her base camp. “On my first visit, I did not take any photographs, but immediately felt energised, and that among the continuous dreary news was hope there could be a different future.” When all the media houses that she’d usually approach rejected her story pitch, Singh decided to look at self-publishing. By then, she and Nasreen, a local resident, had forged a friendship, and the latter insisted on contributing to the book, which resulted in the letter.

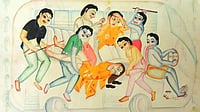

As one flips through the pages, and portraits of women protesters follow in quick succession, they seem to coalesce into a kineograph of sisterhood, ready to fight and face consequences in unison. None of the women bear the visage of protesters that mainstream media trained our eyes to identify, the kind we were bombarded with 24x7. In Singh’s portraits, no one wears an angry scowl, shouts slogans, raises their fists, carries posters, appears tired, famished, fed up or sleep-deprived. Even though Shaheen Bagh was abuzz with songs, slogans and speeches, and hundreds of people milling about, Singh’s women appear in ‘quiet spaces’, far removed from the heat and dust of the agitation. They are dressed in their Sunday best for the photo-shoots, looking anything but the stereotypical protesters.

If viewed outside the context of the sit-in, the portraits will also delight textile experts for the multiple ways the protagonists have styled their headscarf or hijab, shawl and kameez and mixed voguish prints, embroidery and sequins. A glimmer here and a sparkle there lead the eyes to accessories—a glossy clutch, a chain sling bag, nose rings, ear piercings. “One woman distinctly said she had worn her best shawl and favourite pair of sunglasses. Women who saw the polaroids I had taken of them, would turn up the next day with their mothers-in-law or children, who all wanted one of themselves,” Singh tells Outlook.

The written word forms but a fraction of this 137-pager —incorporates English, Hindi and Urdu languages—was presented at the Offset bookshop reading room at the 2022 India Art Fair. Nestled inside the plain kora cotton book jacket, are mostly colourful, full-page portraits of Shaheen Bagh’s women taken by Singh. The book takes the viewer on a visual arc of the life and death of the original protest site that quickly spawned similar models across India; starting with a hand-drawn map and photos of the site, then pulling you into a protest tent from which she brings back individual portraits, and drawings by the children looking at the site from the makeshift art class/crèches here, before ending up at a footbridge once the beating heart of the protests but found desolate on her return to Shaheen Bagh in October 2020. These are interspersed with handwritten poems that were performed on site—including Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega (We’ll Remember Everything) by Aamir Aziz, “which has a line based on my picture of the sky above the protest site —‘Tum zameen pe zulm likho, aasman pe inquilab likha jayega (You keep inscribing your oppression on the ground, we’ll paint the skies with our revolution)’—and is juxtaposed on it”.

That Singh put her heart in every element of the book’s offset print, is visible in her saved Instagram story titled, kitaab. For the woven cover, she reached out to WomenWeave, an NGO at Maheshwar she had visited in February 2020 to photograph the women weavers. “While making the book, I thought it would be a beautiful gesture to incorporate their labour to surround and protect the women of Shaheen Bagh.” Included is a perforated scroll of polaroid prints “meant to be pulled out, framed and displayed on walls, or kept with you in some other form”. Singh would gift one polaroid copy—playfully named as jaadu ka kaagaz (magic paper) by the children—to every woman photographed, and was met with “squeals of delight upon seeing their photograph come to life”. A pleasant surprise was the retinue of young girls who took it upon them to be her ‘assistants’, keeping an eye on her bag and camera. Depending on the day’s pulse, she would carry a medium-format film camera, a polaroid camera, a disposable 35-mm plastic camera, a handheld digital camera or just her iPhone. “On days it got volatile; I didn’t even take out the camera, and just ended up taking audio recordings, which together form an eight minute-long soundscape.”

Quite like the movement’s abrupt end, the book bears a sense of hurry. The pages are not cut in alignment and the cover shows signs of fraying within a day. “I wanted to convey that sense of being unfinished, just like the protest suddenly uprooted without any closure.” But a browse-through Shaheen Bagh’s official Instagram page reveals that the fire of dissent is very much alive, whether in expressing solidarity for the 2020-21 farmers’ protests or protesting against Karnataka’s hijab ban. While the SDMC anti-encroachment drive poses a new threat and continues to keep the neighbourhood in constant flux, for the Shaheen Bagh residents, it is just another day and challenge that needs to be tackled head-on.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Kineograph Sisterhood")