At the start of June, the hottest ticket at the Chinese box office was a cartoon movie about a robotic cat. Nothing surprising about that—an air-conditioned cinema hall is pleasant when the children need some entertainment away from the summer heat of Beijing or Shanghai. But the movie in question was Doraemon: Stand by Me, whose cartoon hero is plucky, funny...and indisputably Japanese.

This doesn’t seem to make sense in the context of the narrative we hear about East Asia. In this version of events, China is rising, and Japan is its number one target. Disputes between the two threaten to break out over the disputed islands in the East China Sea. India and Japan may form a new alliance against China.

In all of these more geostrategic calculations, the human element is often lost. China is often portrayed as a nation simply of nationalist xenophobes with little knowledge or understanding of any other country. And Japan’s public is often portrayed as simplistically right-wing, refusing to acknowledge the reality of Japanese war crimes in China and the rest of Asia during the 1930s and ’40s. That is why it seems surprising when the simplistic narratives are broken and, for instance, a Japanese anime cartoon is a hit in China. The relationship between the two is complex. Japan and China are wary of each other, but also admire many aspects of each others’ societies.

The complexity of the Japanese side is reflected in Sheila Smith’s impressive study, Intimate Rivals. Based on extensive reading of Japanese sources, Smith argues for a more nuanced understanding of Japan’s relationship with China. Her book covers important parts of Japanese government and public spheres, including the diplomatic service, veterans’ associations, health and safety inspectors and nationalist politicians. She succeeds effectively in showing that there is no one ‘Japanese’ attitude toward China, and that sometimes different parts of Japanese society can be counterproductive in their efforts to engage with the rising power of their neighbour.

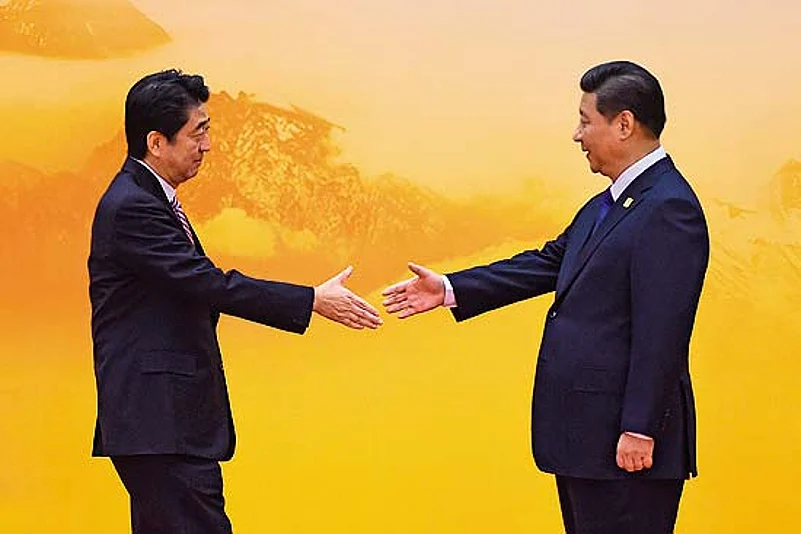

One example surrounds the most contentious of their many disputes: sovereignty over the disputed islands in the East China Sea that the Chinese call the Diaoyu and the Japanese call the Senkaku. In 2012, the nationalistic governor of Tokyo, Ishihara Shintaro, declared that he would purchase the islands from the family who owned them. To avoid the spectacle of the islands falling into the hands of a controversial right-wing figure, the Japanse government proposed to buy them instead. Unfortunately, Beijing chose to interpret this an an attempt to ‘nationalise’ the islands and escalate the dispute. The next few years were marked by alarming encounters between Chinese and Japanese warships and military aircraft around the islands, although the temperature was finally lowered when president Xi Jinping and premier Shinzo Abe shook hands at the apec summit in Beijing in November 2014.

Because the situation remains unstable, one of the biggest questions facing Asia today is: what happens next? Smooth ties between Japan and China are vital to peace in the Asia-Pacific region, yet it is not clear that the two sides have sufficient mechanisms to engage. Smith shows that competing interests within Japan make it hard to formulate policies that allow engagement with Beijing while allowing all domestic constituencies to be satisfied. For instance, there is dispute even within the governing Liberal Democratic Party over whether Abe was right to visit the Yasukuni shrine, which commemorates the spirit of several Japanese leaders condemned as war criminals after World War II. Yet she also, rightly, makes it clear that Beijing needs to allow Tokyo sufficient space to shift policy without constant accusations and confrontation: “Without an opportunity to negotiate its interests with China, the Japanese government will be under great pressure to change some of its most basic postwar policy commitments (p. 260),” such as the constitutional ban on aggressive rearmament. There are many areas where the two sides can come closer.

The fact that a Japanese film be popular in China and that China is a major source of food imports into Japan show that the two countries are linked by ties of economics and culture that belie the lukewarm political associations between them. The world now needs statesmanship from both nations; the costs of a dispute would be paid by many countries well beyond East Asia. Smith’s fine book is an excellent guide to the decisions that their leaders need to make.

(Rana Mitter is author of China’s War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival)