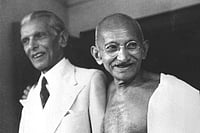

I don’t call myself a “fan” of Ramachandra Guha because reputable dictionaries trace the origin of the word to “fanatic.” Based both on reading his work and some personal interaction, I know that Ram despises fanaticism. The same dictionaries though, also describe a fan as an “admirer or enthusiast.” In such elaborations, I find my own estimation of Ram Guha. I have found no better book to introduce post-independence India to my undergraduate students than his India After Gandhi. A Corner of a Foreign Field rates among my favorite books on cricket. As I write about Kumaon’s history, I often refer back to Guha’s Unquiet Woods. I make sure I read as much of his writing on current affairs that I can. Even though, in recent times, I have disagreed with Guha, I remain an admirer, but not “fan” offering “uncritical devotion.”

“Inside every thinking Indian there is a Gandhian and a Marxist struggling for supremacy.” So began a collection of essays representing the unique range of interests and expertise, as well as the thoroughly engaging prose characteristic of the scholar and public intellectual that is Ramachandra Guha. Guha has negotiated a remarkable and distinctive path between these contending positions in academics and in public debates. That alone is no small achievement. It is a sign of the different polarizations of our own moment that Guha gets lumped together with leftists and labelled part of the “break India into pieces brigade” by right-wing internet trolls. It also displays the ignorance of such intolerant criticism because Guha is as far away as possible from taking such as position. Indeed, a criticism one could make is that his commitment to the national state and its institutions, and modernity more generally, sometimes undermine his commitment to imagining a more just, equitable India.

Guha’s commitment to Indian nationalism and the Indian nation-state is evident is in his disdain for the left and Marxist criticism undermining the legitimacy of the Indian state. His long and ultimately tiresome debate with Arundhati Roy in the 1990s on the Narmada dam (and later, her celebration of the Naxalite movement), was one example of this. His lack of any serious engagement with the Kashmir issue is another. These are different from his affectionate, and sometimes scathing, accounts of faux-anthropological “field work” among Calcutta’s Marxists in the early 1980s where he also distances himself from the intellectual Marxist tradition. Guha has never distanced himself from Gandhi in the same way. It only takes a cursory reading of his output, though, to recognize Guha’s discomfort with Gandhi’s critique of modernity, Gandhian celebrations of indigenous traditions, and romanticized representations of the Indian past.

Guha’s way of negotiating the struggle he mentions has been to embrace Nehruvian liberalism that paid homage to Gandhi even as it celebrated socialist modernity. In times like the present, there are good reasons to be nostalgic about Nehru whether it be his respect for building institutions, or his creating a political culture respectful of diversity in India. Neither seems too important to the present political consensus. I too hanker for times when we had a more liberal political discourse, with leaders who sought to teach the young about India’s place in global history, rather than only how to excel at examinations.

In recent times though, Guha’s celebration of liberal values has been insensitive to the political realities and the historical context of our times. The most controversial recently was his criticism of an article by Harsh Mander. Even as he reiterates his opposition to Hindutva, seeing it as far more dangerous than Muslim communalism, Guha makes it clear that both Hindutva and virtually any form of explicitly Muslim politics, are equally suspect in his estimation. Guha exemplifies this unsustainable equivalence between the majoritarian ideology currently controlling the Indian state and its main targets, Indian Muslims, through a ludicrous comparison between the sartorial choices of Muslims in wearing a burqa or skull-cap and the aggressive displays of trishuls by supporters of Hindtuva. For Guha, visibly Muslim sartorial choices are markers of “the most reactionary, antediluvian aspects of the faith,” as are trishuls (in ways that, inexplicably, turbans or sarees are somehow not). For this, he has been rightly criticized both by the purported victims of Muslim patriarchy and by fellow liberals. He also ignores the way in which Islamophobia in the West or in India has targeted the same markers of identity.

My point though is not to pick on a particularly poor example, but to highlight the larger ideological premise behind this argument. Guha argues that his objection to displays of Muslim sartoriality is “a mark not of intolerance, but of liberalism and emancipation.” He goes on to say that, regardless of their own personal faith, or lack thereof, liberals must consistently and continually uphold the values of freedom and equality. They must promote the interests of the individual against that of the community, and seek to base public policies on reason and rationality rather than on scripture. In this struggle, liberals must have the courage to take on both Hindu and Muslim communalists.

Guha sees the real battle in contemporary India as between “obscurantism, dogmatism, revivalism, and traditionalism on one side and modern liberalism on the other.” This “classical” liberalism also marked Nehruvian modernity and underpins so much of what Guha has written. Such liberalism has no place for “antediluvian” political identities, whether based on religion or caste and chooses to paint them all, even-handedly, as reactionary and obscurantist.

But when and where did this modern liberalism with its supposed commitment to universal freedom and equality actually exist in history? Certainly not in Europe with its imperial disdain for colored folk across the world. And, not in Nehru’s India either, actually. Despite Nehru’s personal liberalism, it was not that issues of religious or caste identity were irrelevant to his time. Nehru’s differences with not just Patel, but with Purshottamdas Tandon, K. M. Munshi, or Rajendra Prasad show considerable support for what we might term “soft-Hindutva” within the Congress party. Nehru had to maneuver, even threaten to resign, to keep these agenda in check. Caste was, if anything, an even more significant issue. As Rajni Kothari pointed out in the 1960s, this was managed through the “Congress system.” Local and provincial leaders deployed parochial networks of caste-based power, bringing in the votes, thus insulating Nehru from the ground realities of realpolitik and enabling him to speak the language of modern, western, liberalism transcending “parochialisms” of caste or religion. The system did not survive Nehru for too long. Indira Gandhi’s recourse to populism signed the final death warrant of the Congress system. The end of Congress hegemony after the Emergency unleashed forces that have transformed not just the political but also India’s social and cultural landscape beyond recognition. Mandir and Mandal are its current political expressions. Guha not only knows this, but has outlined some of it explicitly in his India After Gandhi. That is why it is surprising to see him turn back to the language of Nehruvian modernity in his dismissal of all forms of identity politics.

Far from being “antediluvian,” religion and caste have been an intrinsic part of the history and the social and cultural reality of India. Celebrating an era where these were managed for the benefit of an elite – however liberal or apparently benevolent – is hardly the best way to “continually uphold the values of freedom and equality” in the context of today’s India. In fact, what Guha terms antediluvian is, ironically enough, the product of a modern democracy that has transcended the bounds of Nehruvian management, though also the product of democracy in an illiberal, hierarchical, society. Democracy is what has compelled westernized intellectuals (whether liberal or Marxist) to engage with the realities of religion and caste that remain central to the preoccupations of “the people” – an entity we have debated amongst ourselves in a language and vocabulary far removed from their reality and experiences. To understand, whether to combat or celebrate such politics, it is imperative to locate identity politics within the matrix of power rather than dismiss it entirely via recourse to classical liberal theory. We have to ask whether wearing a skull-cap or carrying a trishul, whether highlighting ones Brahmanism or Dalitness, reinforces the status quo of existing power relations or seeks to challenge it? That, rather than resorting to classical liberal homilies to “promote the interests of the individual against that of the community,” or “base public policies on reason and rationality rather than on scripture” has to be the way to engage with the politics of our times. In other words, the politics of identity is necessarily tied to questions of power, and cannot be understood outside of its context. But such a focus on power might bring us too close to the sort of leftist politics that Guha has already discarded.

(The writer teaches Indian history at Northern Arizona University, US.)