During his bicycle rides to and fro from college, the setting up of a school was all that occupied Anand Kumar’s mind. He realised he’d need a premises because there was no way he could teach anyone inside their own cramped house. But where would he get money for rent? Most kids would have no money to shell out, especially at the beginning.

In any case, the first task was to find willing students. He didn’t have to look far because two of his younger brother’s friends, Manish Pratap Singh and Rajnish Kumar, were eager to learn and move ahead in life. Both sons of clerks, they were no strangers to the ills of poverty and were willing to work hard. With a couple of interested students, Anand then set out to find a place to teach. After some searching, he managed to convince a man he knew in the neighbourhood, Ram Narain Singh, to let him use some space in a house Singh owned. When Anand inquired about the rent, the landlord said he could pay him any sum when he started earning something from his fledgling enterprise. Anand was overwhelmed, and took it as a sign that he was on the right track.

On August 10, 1992, Anand began this little maths club with two students and a classroom. The class was dedicated to the discussion of mathematics, and Anand devoted two to three hours a day, three to five days a week for many months tutoring them. Even some of the teachers who mentored the budding mathematician himself at Patna University began to spend time in his classroom.

What surprised Anand most was how enthusiastic the two young men were to learn. He would often have to remind himself they were basically the same age as him, because the way they would hang on his every word indicated the opposite. Manish and Rajnish were always extremely grateful for the knowledge they were receiving, and soaked up everything that Anand and the other instructors would teach. As a result, they did very well in their Class XII maths exam next spring. Soon after, Anand was tutoring them for their IIT-JEE exam. He immediately knew he was on to something.

Word soon got around about his little tutoring club, and the next thing Anand knew there were maths teachers and other students stopping by just to discuss maths problems and issues with him. His little classroom was soon a meeting place for lots of people to discuss the subject.

Manish Pratap Singh went on to complete a bachelor’s degree in mathematics, and later took a shot at an engineering college entrance exam, which he did not pass. However, he was successful in securing a job with the Union Bank of India, and today is a manager at the Union Bank in Ranchi, Jharkhand. He is, without a doubt, very happy with the way his life changed after Anand decided to tutor him.

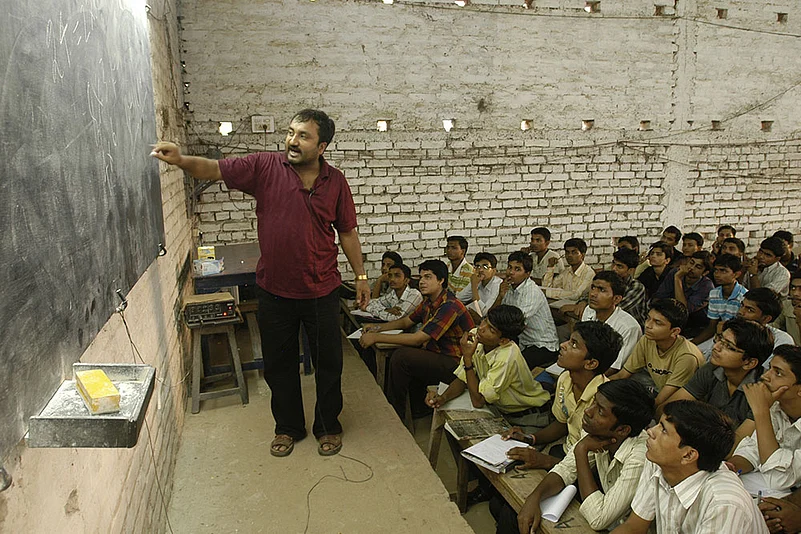

Anand puts students, all attention, through a math lesson

Now, Manish fondly recalls the small, rented room in which the lessons would take place. It was a very humble beginning, but even in those difficult days, he remembers how Anand would talk about taking his two-student school to an international level. At that time, Manish didn’t think the dream would go on to become such a successful, wonderful reality. Thankful for knowing Anand’s brother Pranav, he is proud of being one of the first of Anand’s students and glad that he was there at the inception of the school.

The other student, Rajnish Kumar, was 19 years old then. He knew Anand lived in a small, two-room house in Chandpur Bela with his family and didn’t have any money of his own. Despite this, Anand never demanded any fees from them. They would pay very little, and only when they had the money, always thankful for their teacher’s kindness and passion. Rajnish was glad not only to be part of the beginning of that extraordinary club, but also knew at that early age that Anand was different from any teacher he’d had up till that point. To make the subject interesting to them, Anand would draw connections between mathematics and real life. That was what made the difference in really getting the concepts through to his two young students.

By the time he’d completed his Class XI exam, Rajnish’s grasp of the principles of mathematics had vastly improved. Although he made an attempt at the coveted IIT JEE, he was not fortunate enough to be accepted. Later, he went on to do a bachelor’s degree in economics, and then studied law. After practising law for a short period in the Patna High Court, he moved to Mumbai to pursue a better future. Now he is a legal manager with Aegon Religare Life Insurance Company.

One mathematician influenced Anand greatly and would continue to do so as Anand’s fame as a teacher grew. This man was Srinivasa Ramanujan. Anand would leap at any chance to find out more about his hero. He was very inspired by his work and realised how important Ramanujan’s partnership with G.H. Hardy had been. Anand decided to name his school the Ramanujan School of Mathematics, in honour of this great Indian mathematician, who had offered such brilliant insights into the world of pure mathematics, but sadly passed away at the young age of 32.

Going into 1993, word of mouth soon led to the enrolment of 40 students. The classroom, which was a 15-by-20-foot hall, had a few benches and desks, but there was a good blackboard and plenty of chalk. Only students who had the means paid the nominal fees, which was about one-tenth of what other schools were charging. Anand did the bulk of the teaching, and his brother, Pranav, began handling some of the administrative aspects of the school. Paying the rent for the classroom was stressful, needless to say, but the understanding attitude of the landlord was of enormous help in those early days. Thankfully, enough students paid up regularly such that the arrears never became too large. The level of respect between landlord and tenant grew exponentially over time because the landlord realised his tenant was doing everything possible, and the tenant realised his landlord was giving him a huge opportunity to get established.

***

Once Anand had some income trickling in, however unsteady, he began to think about his own further education. He would pick up mathematics books sold on footpaths, usually by Russian or American authors, and pore over them in the night. He also read several biographies of famous mathematicians, including Ramanujan’s, which he would read and reread for inspiration.

This was a time when the internet did not have the presence it has today. There wasn’t much on TV either, and newspapers also generally engaged themselves in local and national news. So most of the dreams young Anand weaved stemmed from these biographies and other books he could get his hands on. An idea was beginning to take shape in his head. In most books he read, the University of Cambridge was like the benevolent godfather that helped many geniuses discover their greatest talents. Secretly, Anand started to harbour a deep desire to attend this great institution and distinguish himself, not unlike the mathematician greats of old.

Meanwhile, Anand’s younger brother Pranav moved to the Banaras Hindu University, where N. Rajam taught, for a course in playing the violin. This gave Anand an opportunity to visit his brother and discover the Central Library at BHU. The Central Library was a treasure trove. Anand read many journals of mathematics that the library subscribed to. He would make notes and attempt to solve some of the problems posed in these journals and was often immersed in one problem or the other till the librarian had to switch off the lights to get rid of him. Once, after filling almost an entire notebook trying to solve a world-class problem—several pages of scratching everything out and moving on to the next page only to attempt it again—he finally arrived at a solution. It was like stumbling in the dark, and then suddenly, someone switches the light on.

Anand worked on this result and finessed it, and then proceeded to write it down. But his writing was lacking; it was almost infantile. He took his work to Prof D.P. Verma, who was the head of the mathematics department at Patna Science College. Prof Verma helped Anand present his result better by making it publishable. Kaushal Ajitabh, a senior of Anand’s by seven to eight years, was pursuing his PhD at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) at the time. Anand respected him greatly and sent him his paper for review. Kaushal looked the paper over and closely edited it. Both Prof Verma and Kaushal were highly impressed with the originality in thought and encouraged Anand to send it in for publication.

Anand’s wards at their modest ‘hostel’ accommodation

In 1993, after many long days and sleepless nights, a young Anand published an original paper in a prestigious British journal out of the University of Sheffield called the Mathematical Spectrum. The paper was titled ‘Happy Numbers’ and it outlined a new idea about number theory. It also heralded the arrival of a new thinker on the international mathematics scene.

Now that Anand was emerging as a mathematician of promise, Ramesh Sharma, at whose house Rajendra Prasad (Anand’s father) had stayed while studying in Patna, introduced him to Tilak Dasgupta, a freelance journalist from Patna who wrote on poverty, unemployment and the state of inequality. It was Dasgupta who turned out to be one of the greatest influences in Anand’s life. He urged Anand to find a higher purpose for his talents and abilities and not to look for personal profit.

Even now, when Anand has to take any big decisions in life, it is ‘Tilak sir’ that he turns to. Anand and his wife Ritu visit Tilak Dasgupta’s family in Kolkata often. So deeply entrenched is their relationship that the best moments of Anand’s life today are moments he’s able to spend talking to Tilak sir. Such was the impact of the man whom Anand first met in 1993.

Anand went on to publish a few more papers, including one in the Mathematical Gazette. It was around this time that he met the editor of the Patna edition of the Times of India, Uttam Sengupta, through Tilak Dasgupta. There really was something about Anand—as his professor, D.P. Verma used to say, he’d only ever run across two genuine geniuses, the first a brilliant mathematician named Vashishtha Narayan Singh (who suffered mental breakdowns around 1993 and was later institutionalised), and the other, a young man currently studying at his college, Anand Kumar.

Anand made a request to Sengupta. He wanted Sengupta to be the guest of honour at a special ceremony for the winners of a competition Anand had created to challenge his students. Sengupta was intrigued by the story of the Ramanujan School, and how this young student was teaching promising students himself, some at no charge. This was the beginning of a friendship that would continue for a lifetime.

The editor was initially reluctant to grant the request because, as he explained to Anand, he hadn’t exactly been a shining example of mathematical prowess at school, having only scored 40 per cent in his exams in that subject. But the more they talked about Anand’s future goals to write on theoretical mathematics, the more inclined Sengupta became to be the guest of honour at the ceremony. After seeing Anand’s published papers in journals, Sengupta urged Anand to apply to Cambridge. Till now, Cambridge had been only a guilty aspiration, a dream dreamed with eyes wide open, and here was a senior editor being serious about applying. Anand was reluctant, but something akin to hope tugged at him.

In April 1994, Anand filled up the application form for Cambridge, attached his published papers and sent it off without paying a single penny as application fee or anything of the sort. In the days that followed, he tried to forget about this application. Why did I send it? All those professors must be sitting and laughing at me, thought Anand, as he lay awake at night. Cambridge jayenge janaab, he derided himself.

(With permission from Penguin.)