“There is no Hindu canon,” declares Wendy Doniger in The Hindus. “The Vedas did not constitute a closed canon, and there was no central temporal or religious authority to enforce a canon had there been one.”

This is a curious argument in defence of heterodoxy. Canons don’t spring fully formed like Athena from the head of Zeus, or drop from the lips of a passing Archangel. Someone has only to do the hard work, and it’s never too late to make a nice hard canon.

As Doniger says, Hinduism as we know it today “is composed of local as well as pan-Indian traditions, oral as well as written traditions, vernacular as well as Sanskrit traditions, and nontextual as well as textual sources.” That’s good news—plenty of material there to choose a canon from.

Back in the 16th century, the Church found itself up the creek without a canon. Plagued by fifteen hundred years of heresies and heterodoxies, disagreements over the sacraments and the scriptures, not to mention a perfect storm of lusty, busty images in Renaissance religious art, the Catholic Church sat in ecumenical council between 1545 and 1563 and decided, once and for all, what was IN and what was OUT.

Index of Prohibited Books

It took the Church just over 1500 years—from the crucifixion of its founder to the Council of Trent—to decide which of its written books and unwritten traditions were truly sacred and which were profane (and which were to be banned).

In its final session in 1563, the Council laid down the law on sacred images. These, the Council grudgingly conceded, were beneficial to the illiterate but it decreed that, in the “sacred use of images, all superstition shall be removed, all filthy quest for gain eliminated, and all lasciviousness avoided, so that images shall not be painted and adorned with a seductive charm…”

This brings me to the cover of Doniger’s The Hindus, on which “Lord Krishna is shown sitting on buttocks of a naked woman surrounded by other naked women.” The question which troubles all right-thinking Hindus, as it did the good men of the Church, is whether it is lawful or even in good taste to depict the Lord and his saints in a manner ill suited to polite society.

Krishna with gopis—composite image

Did the NOTICEE wantonly indulge “in unlawful act by showing photograph of Hindu God sitting on the lap of a naked woman & surrounded by naked women”? India has a long and dismal tradition of showing images of gods (and angels, and demons and kings) sitting on the buttocks of naked women. It is one of those kinky traditions that has persisted down the ages, at least from the 17th century CE. The Persians are to blame, of course, but once the Mughals brought these composite images into India, the Hindus embraced the style with a deplorable enthusiasm. They painted naked women by the score, in knots, in arches, in chariots and palanquins, often shaped into horses and elephants, more often than not with a gent sitting on the buttocks.

Composite Animal

Arguments from tradition are absurd. Are we supposed to tolerate licentiousness on this scale just because our ancestors were over-sexed louts who should have known better? This whole business of privileging pornographic images simply because they are very old or have religious origins is suspect. (The Information Technology (Amendment) Act 2008 penalizes the publishing or transmission of “any material which is lascivious or appeals to the prurient interest,” but, it adds reverently, not if they are “kept or used for bona fide heritage or religious purpose”).

It’s no use saying that such images “possibly represent the belief in the internal unity of all beings and illustrate the doctrine of the transmigration of souls through successive reincarnations”. The Shiksha Bachao Andolan may not be au courant with the doctrine of the transmigration of souls, but I’m pretty sure they know souls don’t transmigrate on the backsides of horse-women.

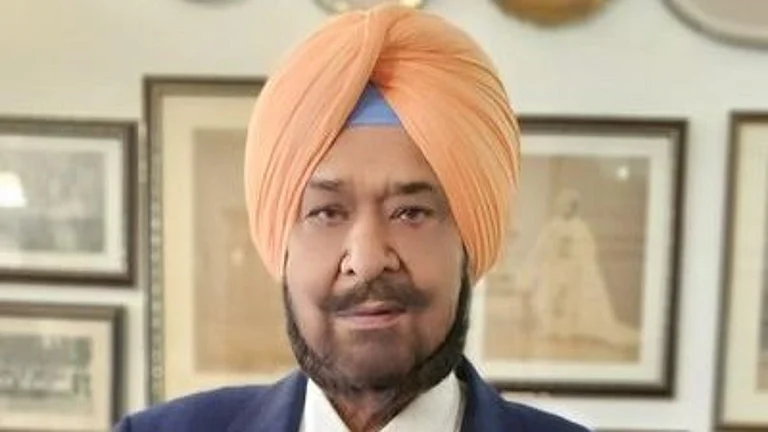

As Dina Nath Batra points out, showing a deity perched in such “a vulgar, base perverse manner” on a woman-horse (nari-ashva) is not only calculated to outrage the religious feelings of Hindus, it is “likely to cause the offence of rioting.” Mr. Batra is 84 years old and if this lewd image can provoke him to riot, there’s no telling what effect it could have on the general populace.

“The rider on the horse is an enduring Hindu metaphor for the mind controlling the senses,” the remorseless Doninger goes on, “in this case harnessing the sexual addiction excited by naked women.”

Enduring metaphor, my ass. Even the horse has a boner.

Doniger, as Shri. Batra has perceptively observed, is hungry of sex. The Hindus: An Alternative History mentions sex 310 times (I counted, twice), far more often than the soul (56) or atman (18). For similarly perverse reasons, Doniger writes about beef twenty-five times—in a book ostensibly about Hindus!—but wholesome vegetables hardly find a mention in her work.

It is evident from the book’s cover picture, and her repeated drooling references to it in the text, that Doniger has a thing about animals. “Three animals—horses, dogs, and cows—are particularly charismatic players in the drama of Hinduism,” she claims with breezy insouciance, and then prattles on about horses (802 references; including gratuitous drivel about mares being the symbol of the evil female, “oversexed, violent, and Fatally Attractive”), and dogs (481) while the cow, that most Hindu of animals, barely clocks in with 258 appearances.

The dog, we know, is as central to the Hindu faith as the platypus is to Semitic religions.

But I digress.

The lewdness of pagan and Renaissance religious art has vexed the faithful down the ages, as students of the genre have noted. Michelangelo’s frescoes are packed wall-to-wall—and right across the ceiling—with nudity and licentiousness.

The Last Judgment

Most churchmen were appalled by The Last Judgment. “It was a very disgraceful thing to have made in so honourable a place [i.e, the Sistine Chapel] all those nude figures showing their nakedness so shamelessly, and that it was a work not for the chapel of a Pope, but for a brothel or tavern,” the papal Master of Ceremonies is reported to have said, with admirable restraint.

The paint was hardly dry on The Last Judgment when Council of Trent, shaken to the core by the “spectacle of martyrs and virgins in improper attitudes” inside the Pope’s chapel, issued their decree against lasciviousness in religious art.

On the literary front, the Council struck equally powerful blows in the name of chastity and decorum. By removing the raunchier and more suspect texts from the hitherto loose canon of Christianity and sequestering them, sometimes in the Apocrypha, sometimes in the Index Prhibitorum and occasionally in a bonfire along with the author, the Council cleaned up the canon. This process continued with the Protestant and Reformed Churches. There is no such thing as a single Christian canon.

Today, if the Christian artist wants to sneak a nude or two into his Art, he has to make do with Bathsheba or, if pressed, the nameless Shulamite from the Song of Songs (and I am at a loss to explain how that scandalous poem—“Your lips are like a scarlet thread, and your mouth is lovely / Your two breasts are like two fawns, twins of a gazelle that graze among the lilies”—got into the Bible. No doubt Doniger and her crew will call it an allegory—or an enduring metaphor—symbolic of the union between Christ and the Church or, alternatively, Christ and the individual soul. A likely story. There are artistic interpretations of the Dream of the Shulamite that would cause comment in the Playboy Mansion).

Bathsheba at her bath—Rembrandt

But in the centuries before the Council’s decree, the Christian artist had a smorgasbord of licentiousness to choose from. Michelangelo, in those spacious pre-Tridentine days, had a free hand. He peopled his vast frescoes with martyrs and virgins in improper attitudes and hardly a stitch between them. Take the saints Blaise and Catharine in The Last Judgment. Today, the saintly Catharine, draped in green robes, bends before St. Blaise while the man modestly averts his eyes. It was not always thus. Michelangelo’s muscular Catharine was clothed in nothing but virtue while Blaise gazed at her derriere with pop-eyed fascination. The two, moreover, were presented in an improper attitude that in a later age would be called twerking.

It so disturbed the elders of the Church that they hired an artist to scrape away that part of the fresco and repaint the two saints as we see them today. (This virtuous artist, da Volterra, went on conceal so many of the genitals and bottoms in The Last Judgment with loin cloths and fig leaves that he was dubbed “Il Braghettone” or Daniele, the Breeches-Maker).

St. Blaise and St. Catharine—from The Last Judgment

Artists, like professors in the University of Chicago, claim to believe that a beautiful body is the physical representation of a beautiful soul. When noted Sanskritist, theologian and painter, Dr. Jose Pereira a.k.a Goa’s Michelangelo, exhibited “nude and derogatory paintings of Hindu Gods” in an exhibition in Goa circa 2010, the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti questioned his motives in language reminiscent of the Shiksha Bachao Andolan’s notice to Doniger. “Instead of painting Hindu Deities in this way, why didn’t Dr Pereira paint Jesus Christ or Mother Mary in the nude?” they asked plaintively. “There are many examples of cruelty towards women in the Bible. Dr Pereira could have painted these pictures to make people aware about his own religion.”

Seriously, what is with these Jewish, Muslim and Christian artists? Can’t they make people aware of their own religions?

Dr. Pereira, quoting chapter and verse from Gita Govindam—in the original Sanskrit—tried to explain that Krishna is the Embodier of Eros (krsna murtiman iva srngara) and that his painting was based on a mural in Padmanabhapuram Palace. Dr. Pereira’s Krsna, clad immodestly in a sketchy yellow garment, “lies in a bower […] attended by five cowgirls, golden brown in color, engaged in intimate love-play with the god.”

Krsna, Embodier of Eros—Jose Pereira

In the heat of the moment, it did not occur to the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti to inform Dr. Pereira that, in his own Catholic tradition, Embodiers of the Eros, far from dallying with naked cowgirls, are found screaming in the Second Circle of Hell.

Janaki Nair, in these pages, has referred to the “brilliant murals at the Cochin Palace at Mattancherry, where Krishna does not waste a single digital extremity of his eight hands and two feet in pleasing his gopis.”

Krishna with gopis—Mattancherry Palace

The temples and palaces of Kerala are regrettably full of gods and cowgirls in improper attitudes. One is happy to learn from Dr. Nair that the sexually explicit murals in Guruvayur Temple are now being tastefully covered with gold plate.

There is nothing like a little gold plate, or whitewash—or dynamite—to set right the wrongs of the past.

What, then, is an acceptable image of God?

Satvik image of Sri Krishna (Hindu Janajagruti Samiti)

The Sanatan Sanstha has thoughtfully provided a ‘satvik image of Sri Krushna’, based on Spiritual Science, which should please everyone. It depicts the theophany of Krishna as a gigantic figure flanked by dhoti clad devotees. The demonstrably impious, as can be inferred from their green pathani suit, jeans & T-shirt, and kurta and Gandhi-cap, flee in terror. Two enemies of dharma are struck dead—one of them presumably for wearing a purple shirt—and lie bleeding at the Lord’s glowing feet.

Significantly, while there is a female bhakt in the picture, she is modestly clad in a saree and is not being groped (ref. Janaki Nair) nor having her posterior sat upon (vide Wendy Doniger).

All that remains is for us to reform the Hindu canon. From the hundreds, if not thousands of ancient texts that jostle for space in the Hindu library, let’s pick a few good ones. The Vedas and Upanishads would find a place in the Canon, as would some of the Puranas and less controversial bits of the two epics, especially the Bhagavad Gita (though the frumious Doniger mocks it as a book privileged by Euro-Americans and “not always so highly regarded by “all Hindus””, but what does she know?)

Doniger notes with ill-concealed satisfaction that there was no temporal or religious authority to enforce a Hindu canon, but that does not mean there cannot be one now. If the Heads of the Mutts and other Hindu saints were to sit in Council, I am sure they could anthologize, bowdlerize and sacralize a few suitable texts to generate a Hindu canon that would find favour with all right-thinking Hindus.

Surely that would, in the wise words of the Council of Trent, “repress that temerity, by which the words and sentences of sacred Scripture are turned and twisted to all sorts of profane uses, to wit, to things scurrilous, fabulous, vain, to flatteries, detractions, superstitions, impious and diabolical incantations, sorceries, and defamatory libels.” There would be plenty of material left for culture vultures to pick over. Painters like Husain and Pereira and others ‘hungry of sex’ like Doniger can go through the non-scriptural and profane texts and do with it what they will.

If they wish to paint cowgirls entwined in the shape of a camel with a minor forest god sitting on their buttocks, let them do it, I say.

This piece was first published in Kafila