The 1940s was the decade of struggle for Indian cricket. Unable to play international cricket in the first half of the decade due to the Second World War, India returned to playing Test cricket in 1946, with their third tour of England. However, with the country in the throes of independence and Partition, the domestic cricketing structure too was in turmoil and this was reflected in the team’s performances both at home and overseas. Despite all this, Indian cricket did make some significant advances. In the individual realm, the two men who made Indian cricket their own in the 1940s were the two Vijays: Merchant andHazare.

In the absence of international cricket, the nation’s attention was focused on the domestic scene, primarily on the Bombay Pentangular, the foremost tournament in colonial India, and the Ranji Trophy. Cricketers who made these tournaments their own, breaking records with élan, were Vijay Merchant and Vijay Hazare. In 1941-42, Merchant had recorded the highest score in the Pentangular, scoring 243 for the Hindus against the Muslims. In the very next season, Hazare wrested the record, scoring 248 against the Muslims. However, he hardly had time to savour the feat, as Merchant scored an unbeaten 250 against the Rest. Not to be outdone, Hazare, batting for the Rest, replied with a mammoth 309. All of these records were broken in the spate of a week, between 29 November and 6 December 1943.

The competition continued into the Ranji Trophy. Batting for Bombay against Baroda, Merchant made 141. Hazare replied with 101. In the next match against Maharashtra, Merchant scored 359. (This was eventually surpassed by B.B. Nimbalkar’s 443 for Maharashtra versus Saurashtra in 1948-49.) This is how the two men batted in 1943:

Vijay Merchant: 865 runs in 5 innings at an average of 288 with three 100s and two 50s.

Vijay Hazare: 1423 runs in 11 innings at an average of 177 with five 100s and three 50s.

With the Vijays in such imperious form, India defeated the Australian Services XI under Lindsay Hassett. This was another unofficial tour, a feature of colonial Indian cricket. With victories under their belt, the Indians were confident of performing creditably in England. However, from the very start of the tour, rumours were rife of a bitter feud between the captain, the Nawab of Pataudi Sr., and Vijay Merchant. After Merchant got a spectacular 242 against Lancashire at Old Trafford, he was the cynosure of all eyes. His rival, Hazare, eclipsed Merchant’s feat a week later against Yorkshire at Sheffield, scoring 244.As soon as Hazare crossed Merchant’s score, Pataudi declared the innings.

To observers, it seemed as if all Pataudi had wanted was that Merchant’s effort should be eclipsed. That the rumours were not without foundation is proved by the unearthing of a confidential letter written by Mushtaq Ali to C.K. Nayudu on 1 August 1946 from the Carlton Hotel in Taunton. The letter goes thus:

"…Now Sir I must tell you something from this end, how Indian cricket is and how we are doing in this country. In my humble opinion this tour is worse than (the one in) 1936, the same old trouble: no team work at all. Every member of the team is for himself. No one cares for the country at all. Amarnath is the cause of all these things. Pataudi is a changed man… and is very much against the Indian players. C.S. Nayudu plays in the team not as a bowler but as a fielder only… Whenever a county player is set for a big score you will find the Indian captain back in the pavilion. As a captain he is worse than a school boy…I am very much fed up with him as are the other members of the team.

Believe me Sir, the second Test match was ours after such a nice start. We collapsed because he sent in Abdul Hafeez at No 3 instead of going in himself… I think Merchant is a much better captain than this fellow."

In such a situation, losing the Test series only 0-1 was not a bad performance. In fact, the Indians played brilliantly in most tour games, the performances ofShute Banerjee and Chandu Sarwate against Surrey being the stand-out efforts. At the Oval against Surrey, going into bat at numbers 10 and 11, Sarwate and Banerjee got together when the total was 205-9. They eventually parted at an unbelievable 454 all out, adding 249 runs for the tenth wicket. Banerjee was bowled by Jack Parker for 121 while Sarwate remained undefeated with 124. This was the first time in a match of some consequence in international cricket that numbers 10 and 11 had both scored centuries. Banerjee, however, wasn’t rewarded with a Test berth. The argument advanced was that he was in the side as a bowler and not as a batsman. He finally got to play Test cricket extremely late in his life, in 1948-49, against the West Indies, picking up five wickets in the match. And that was his first and last match.

The batsmen too had their moments. In the match against Sussex at Hove, a contemporary newspaper noted,

"In exactly 365 minutes, the touring team scored 533 for three before the Nawab of Pataudi declared the innings closed. Chief run-getters were Mankad (105), Pataudi (110 not out), Merchant (205) and Amarnath (106 not out). Though George Cox replied with 234 not out, with little support from his country colleagues, Sussex were beaten by 9 wickets."

At the end of the tour, The Times headline said it all: "Indian Cricket Tour of England Unqualified Success."

Pataudi Sr. introduces the Indian team to King George.

In the piece that followed, A.E.R Gilligan went on to suggest that the success of the team owed largely to the unity among the players, a reminder of how well the Indians were able to conceal their internal differences. On or off the field, he wrote, they behaved and played like true sportsmen, taking their reverses in gallant spirit…

"No matter where the team was playing, the same story can be told of record gates, because the British public realized that the Indian team would always play cricket in its greatest sense. Whenever they appeared there was always something to look forward to, either excellent batting and bowling or glorious fielding…the visit of the 1946 India team has been a real success from every standpoint."

Gilligan concluded saying,

"In all future matches, particularly when visiting Australia in 1947-48, India will, I am convinced, give Australia a real run for their money."

Alas, that was not to be.

The Indian team arrives in Adelaide, Australia, 1947-48.

In Australia, the Indians lost the series 0-4, a result that appears all the more mystifying given the Indian performance in the first class matches of the tour. Before the first Test at Brisbane, Amarnath, the captain, had established himself as a true leader with a grand 228 against Victoria, an innings Victor Richardson, a distinguished member of Bill Woodfull’s 1932 Bodyline side, ranked as "one of the greatest ever played" in Australia. Mankad was regarded as the world’s premier slow bowler, even better than Hedley Verity. He had almost singlehandedly won India the match against the Australian XI with figures of 8-84. With quality batsmen like Hazare and Phadkar, the latter making his debut on this tour, the Indians certainly promised to put up a tough fight. And with Kishenchand, Sarwate, C.S. Nayudu and Sohoni showing signs of reaching their best before the first Test, not even the most ardent of Australian supporters anticipated the one-sided contest that followed.

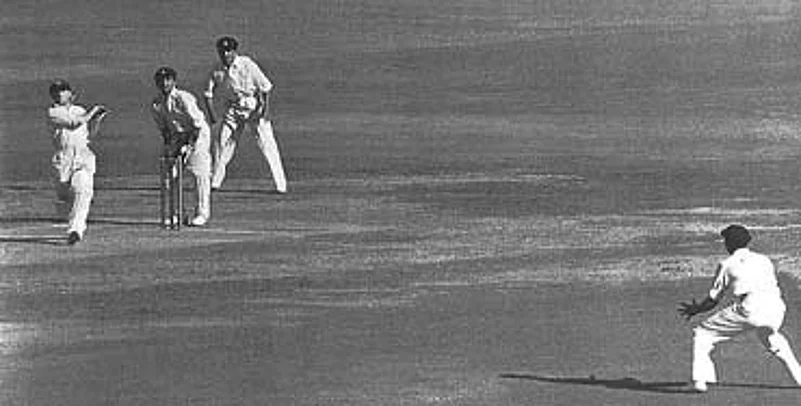

Bradman hitting Hazare: At 39, Bradman was still at his best and hit three centuries and one double century against India in 1947-48.

And this rout, it can be asserted, was almost solely orchestrated by Donald Bradman. Though thirty-nine, Bradman was still at his best and his scores – 156 for South Australia, 172 for an Australian XI (his hundredth first class hundred), 185 in the first Test, 132 and 127 not out in the Third Test, 201 in the fourth Test and 57 retired hurt in the fifth – bear testimony to his contemptuous dominance of the Indian attack. It must be said though that India might have done better but for the fact of India’s Partition, which had robbed the team of the services of Fazal Mahmood and Mushtaq Ali. Amidst the ruin, the lone star was the nation’s premier batsman – Vijay SamuelHazare.

At Adelaide, in the fourth Test of the tour, the Indians began their first innings facing a daunting Australian total of 674. Though Amarnath and Mankad started well, with the former scoring a strokeful 46, half the side was soon bundled out for 133. It was then that Hazare found form. With an able ally in Phadkar, the Australian crowd witnessed a spectacular recovery and the Indians ended the day at a respectable 299 for 5. Eventually, with Hazare out for 116 and Phadkar making 123, the Indians were all out for 381 and followed on.

In the second innings the Indians were again under pressure and once again it was Hazare to the rescue. As the newspapers of the time noted,

"It didn’t matter what the ball was, on or outside the off stump, what its height or pace, it was played with amazing certainty…It was a display of batsmanship, which has very seldom been equalled, certainly not surpassed and never dwarfed. It was not so much the pace at which the ball travelled. It was the supreme artistry of it all."

It was batsmanship at its flawless best. This innings of 145 against a brilliant Australian bowling attack consisting of Miller, Lindwall and Toshack overshadowed the end result and even though India were all out for 277, they were hardly disgraced.

Looking back on that Adelaide Test, Hazare had mentioned to me at a conversation in October 2004, only a few days before his death: "Bradman seemed impressed with my batting and we became close friends. Some years on, he even found time to write a foreword for my book."

Indian players wait for the rain to stop. In the front row are Amarnath (extreme right)and Hazare (next to him).

Although Hazare will always be remembered as one of India’s all-time great batsmen, he was also a reasonably good bowler. In fact, for him getting Bradman out in 1947-48 was no less a feat than scoring consecutive hundreds at Adelaide. As he recalled:

"Though I got a couple of hundreds on the tour, another eternal memory is that of getting Bradman out on three occasions... While my first two successes against him had little practical value – he had scored well over 150 by then – on the third occasion I bowled him for 15.

On that day, I was bowling outswing, and he seemed content in leaving most deliveries outside the off stump. It was then that I bowled an offcutter, which made its way through his bat and pad and crashed into the stumps. The bail was retrieved from well over a distance of 50 yards and the maestro seemed shocked. I could not believe what had happened, more so because he had been in prime form."

THE MIGHTY WEST INDIANS' FIRST TOUR OF INDIA. 1948-49

The 1948-49 West Indies team to India with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. This was the first time the mighty West Indians were in India.

The West Indies were first due to come to the subcontinent in 1946. However, that tour had to be cancelled on account of the high cost of air travel. The Times of India reported on 14 September 1946,

"The West Indies cricket team will not tour India this winter. The BCCI, after ascertaining all the facts regarding travel facilities of the tourists, have found that a sum of 10,000 pounds would be required. No sea passage is available and the West Indies team would have to travel by air via England to India and back... The total expenditure on the West Indies team, on account of lack of sea passage, would be, it is felt, beyond the capacity of India, and consequently the BCCI has, very reluctantly, cancelled the West Indies tour this year and hopes for their visit some years later."

More than the cricket, it was the bitter conflict between the captain, Amarnath, and the Board president, A.S. De Mello, that hogged the limelight during the 1948-49 tour. De Mello prepared a list of twenty-three charges of indiscipline and misdemeanour against Amarnath. The most startling of these was that Amarnath, stand-in captain and selector along with P. E. Palia and M. Dutta Roy, had accepted a bribe of five thousand rupees from officials and cricket enthusiasts in Calcutta to include Probir Sen of Bengal for the fourth and fifth Tests.

In retaliation, Amarnath went on the offensive, saying that "the country will soon know the other side of the picture and will then be in a position to judge and decide as to whether the charges framed against me are correct." He also said that he had "sacrificed and suffered much – not only financially but in friendship as well – out of devotion and loyalty to the Board and its president" and demanded that in the interests of Indian cricket the Board should make public the charges made against him. "While I do not expect any favour from the Board, I certainly hope they will play cricket."

Finally, on 5 June 1949, Amarnath addressed a press conference in Calcutta where he distributed to those present a thirty-nine page statement in an attempt to prove that De Mello was out to settle a personal score with him. In this booklet, he replied to each of the charges, emphasizing that the Board, in effect De Mello, would never make amends for the grave injustice done to him or to the sport in general.

From the cricketing standpoint, the tour belonged to the great West Indian batting legend Everton Weekes, whose total tally against India stands at 1495 runs at an everage of 106.78. An illegitimate child who joined the army to ensure that he was not discriminated against, Weekes looked back on the Indian tour when we met at his Barbados home in May 2005:

"I always loved playing against India. It had nothing to do with their bowlers. Let me make something clear, Mankad and company were some of the best I had faced in my career.

It was just that I was always in form when I played India and managed to score some valuable runs for my side."I had managed to get a hundred against England before we came to India. Never did I imagine that the 1948 India tour would make me a world record-holder, a record that would stand the test of time for over fifty years. I had always played my cricket for satisfaction and never cared much about records. Cricket, you must remember, wasn’t simply a game for us, it was life.

"The first Test match of the tour was in Delhi and there was major enthusiasm all round. It was some time in November and I was fortunate to start the tour with a century (128), an innings that set the tone for the rest of the tour. This innings gave me a lot of confidence and when I played at the Brabourne Stadium in Bombay, one of the best cricket grounds I have played in, I was stroking the ball freely and the 194 that I got was a just reward for my efforts. I followed this up by scoring a century in each innings –162 and 101 – at Eden Gardens, Calcutta, and still remember the praise the crowd heaped on us. After getting these centuries on the trot, I was suddenly aware that history had been made and was determined to continue in the same vein at Madras. However, when it seemed to me that the century was just a few shots away, I was run out for 90. It would have been my sixth successive Test century. I don’t regret this incident, however. In fact, I think that getting out on 90 made my world record all the more poignant. But let me end by saying that had there been technology then, I would not have been given run out. The umpire had made a mistake!"

What fun: Indian players run back to the pavilion ( below)

From the Indian standpoint, they did well to save the first two Tests, though they lost the third. In the fourth and final Test, they started well, bowling the West Indies out for 286. However, the match soon turned the West Indies way with the Indians all out for 193. Finally, the Indians were set a target of 361 in 395 minutes. S. K. Gurunathan, one of India’s best cricket journalists ever, describes the excitement and eventual trauma of this fascinating run chase:

"Modi (86) and Hazare, the overnight not out batsmen, remained unbeaten till lunch on the last day and there was every chance of India winning the match with a score of 175 for three. But the bid for victory was somewhat delayed. After lunch the batsmen started attacking. Modi and Mankad were out. Hazare (122) was masterful, but was bowled by Jones when victory was in sight.

"Excitement began to mount after tea. Banerjee and Adhikari did not stay long. But Phadkar and Ghulam Ahmed carried on. Six runs more and a minute and a half to go! But the stumps were pulled and the match was left drawn.

The fight had been glorious. Phadkar played valiantly. It was a memorable match. For the excitement it caused towards the close, it still remains the most exciting match India have played so far."