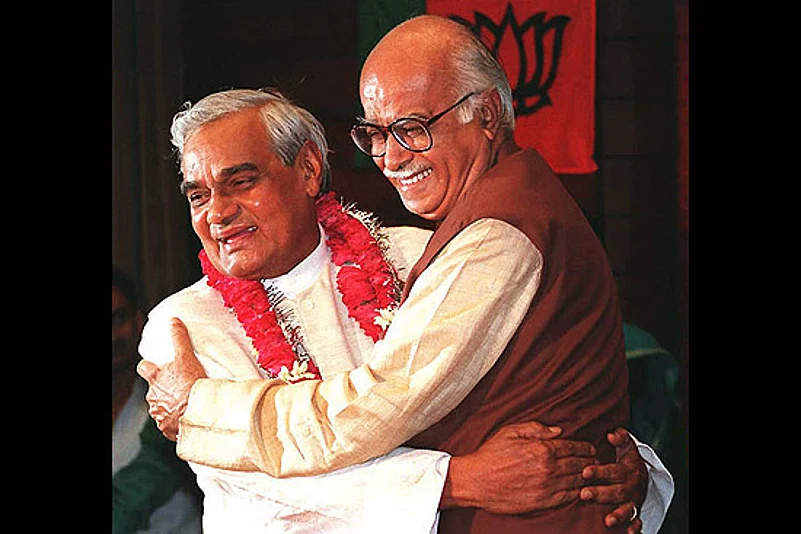

No one, not even longtime Congress supporters, would disagree with the last sentence in the epilogue of The Saffron Tide: The Rise of the BJP by Kingshuk Nag. “The BJP has arrived and will remain the primary pole of Indian politics in the foreseeable future,” writes Nag, a journalist with The Times of India. If the credit for transforming India’s polity from unipolar, with the Congress remaining the only pole for decades, into bipolar, with the Bharatiya Janata Party emerging as the competing pole after the 1990s, goes to the duo of Atal Behari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani, there is only one claimant—Narendra Modi—to the spectacular success of making it unipolar again, at least for the time being.

But I completely disagree with Nag—confident that all except the most fanatical BJP supporters would share my view—when he presents the following assessment: “One last word.... The first republic that was crafted by Jawaharlal Nehru in the 1950s is making way for the second Republic that will be based on a completely different paradigm.” Without in the least underplaying the scale and significance of Modi’s electoral achievement, I affirm that the change of government in 2014 is not going to result in any change in the foundations of the Indian republic.

No doubt, futile efforts are currently being made towards that end. Mohan Bhagwat, the chief of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, which has enormously tightened its control over today’s BJP, has aggressively resurrected the ideological dogma of the RSS that India is a ‘Hindu rashtra’ and that all those living in India are Hindus. No BJP leader has so far shown the courage to contradict Bhagwat on this dangerous and delusional claim. But if at all NDA-II, which is essentially a BJP-I government, dares to change the fundamental paradigm of the republic—memorably described by the Supreme Court as the ‘Basic Structure of the Constitution’, of which secularism is an inseparable part—that will surely be the beginning of the end of Modi’s prime ministership.

Nag, whose other works include the bestselling The NAMO Story: A Political Life, deserves praise for having written an informative chronicle of the birth, evolution, rise and fall, and the recent rise again of the BJP. Since there are so few good books on the history of the BJP, with Advani’s autobiography My Country My Life (2008) being a notable exception, The Saffron Tide partially addresses a need of the growing number of Indians and foreigners interested in this subject. However, it reads more like a newspaper reporter’s narrative. Nag would have served his readers better if he had taken the trouble of donning a scholar’s cap and rigorously explored the ideas, innovations and internal tensions, especially the BJP-RSS ties that have both shaped the BJP’s rise and also clearly marked the limits of its rise.

Modi’s success in crossing the impossible-looking target of 272+ may have created an impression among both BJP supporters and many of its demoralised opponents that the ‘saffron tide’ is now unstoppable. And this may even embolden some in the RSS-BJP combine to attempt to saffronise the republic’s polity and society. Modi should avoid this misadventure for his own, and India’s, sake. And the reasons for this can be found in the BJP’s own history.

For example, is it not intriguing that the words ‘Hindutva’ and ‘Hindu Rashtra’, which the RSS believes are the non-negotiable markers of India’s national identity, do not even appear in the constitution of the BJP? When Atal Behari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani resurrected their party from the debris of the self-destructive Janata Party and founded the BJP in 1980, they scrupulously anchored it in the principles of liberal democracy, secularism (they preferred the term ‘positive secularism’, but secularism nonetheless) and even socialism of the Gandhian kind. They did so because long years of struggle in the midst of India’s social and political diversity had convinced them that the BJP could not succeed by becoming the political wing of the RSS.

Indeed, it is absolutely certain that the BJP would not have so closely embraced the Sangh parivar in espousing the issue of the Ram temple in Ayodhya had Indira Gandhi’s assassination not taken place, had the newly founded BJP not been reduced to a pathetic tally of two in the 1984 ‘Shok Sabha’ elections, and had then PM Rajiv Gandhi not made the mistake of capitulating to the pressure of Muslim fundamentalists in the Shah Bano matter. However, the BJP painfully realised that even the temporary Hindu upsurge created by the Ayodhya movement was not enough to catapult it to power. The party required the innovative genius of the Atal-Advani team, which crafted the NDA strategy, and the charismatic and sagacious leadership of Vajpayee, who believed in the idea of an inclusive India, to succeed in 1996, 1998 and 1999. Only at its own peril can Modi’s BJP afford to reject these vital learnings from the party’s past.

Nag’s narrative is useful in helping readers understand the BJP’s unease in reaching out to Indian Muslims and Christians. But it is weak in examining the ideological innovations made by the BJP and by its previous avatar, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (which was founded in 1951 by Syama Prasad Mookerjee, a non-RSS leader). For example, Nag devotes just one paragraph to Integral Humanism, a highly original and non-divisive treatise by Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya (1916-1968), which the BJP regards as its ‘basic philosophy’. Upadhyaya, the principal architect of the Jana Sangh after Mookerjee’s death in 1953, is one of the most idealistic and creative socio-political thinkers in modern Indian history. Sadly, he’s also one of the least recognised outside BJP circles. Had this widely respected leader not been murdered in mysterious circumstances at the peak of his political life, much of India’s subsequent political history would have been different.

Nag rightly mentions that the BJP pays only lip service to ‘integral humanism’. Upadhyaya’s other bold and innovative idea—that of an India-Pakistan confederation, a precursor to the SAARC idea, which he propounded jointly with the great socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia in 1964—has become an anathema for today’s BJP, and even to the RSS, though the latter has not given up on the idea of ‘akhand (Hindu) Bharat’.

Nag also devotes only two cursory paras to Advani’s Pakistan yatra in 2005, which (unsuccessfully) sought to script another ideological innovation. The RSS-VHP leaders’ vicious attack on him for his courageous and unorthodox (yet, factually incontrovertible) remarks on Mohammed Ali Jinnah badly wounded his political career. Yet, history will absolve Advani. The sincere initiatives of Vajpayee and Advani to normalise relations with Pakistan, without compromising on the serious issue of Pak-sponsored terrorism, along with similar efforts by other leaders in the past and the future, will surely bear fruit one day.

Nag’s book, which needed better editing, begins with a totally erroneous premise in its introductory chapter. Wrongly describing the Congress as the “original Hindu party of India”, he writes, “The story of Indian politics is the saga of who captures the Hindu vote and how. The Congress controlled this vote for a long time but now has given way to the BJP.” In doing so, he contradicts himself, because he concludes his book by stating that the basic paradigm of (Modi’s so-called) ‘second republic’ will be “completely different” from that of Nehru’s “first republic”. The truth is that the heart and soul, as well as the institutional sinews of the Indian republic, are intact and robust. If today’s BJP thinks that it can rule secular India by capturing and retaining only the Hindu vote, the republic will swiftly find ways to pull it down from its newly gained pole position.

(Kulkarni, who was associated with the BJP for 16 years, quit the party in early 2003 due to ideological differences. He was a close aide of Atal Behari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani.)