Bruce Riedel has spent a lifetime in CIA, advising four US presidents. He was chosen by Barack Obama in 2009 to oversee an inter-agency review of the Afghanistan war. His book, which assesses the impact of Pakistan-US relations on global jehad, was released before Osama bin Laden’s dramatic killing on May 2. Far from making it redundant, events have only heightened the book’s relevance.

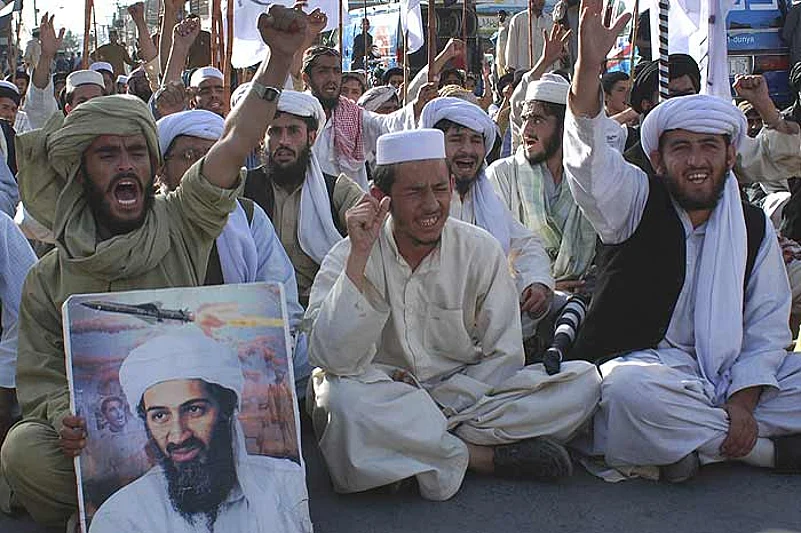

In this highly readable and timely book, Riedel not only recounts the coalescing of US arms, Saudi money and Wahabi Islam and Pakistani President Zia-ul-Haq’s bigotry, but rearranges known material, contextualising and juxtaposing it with his recall of those events. Suddenly, suspected linkages crystallise, clues become evidence and the sinister plot unravels. He describes global jehad with Zia-ul-Haq as the midwife, Mullah Omar as the protector and bin Laden as the charismatic leader.

A fascinating picture emerges of cooperation from the earliest stages between India-specific groups like the Lashkar-e-Toiba or Jaish-e-Mohammed and the core jehadi movement that spawned in Afghanistan and captured it between 1983 and 2001, under the tutelage of the Pakistani army/ISI. Riedel says the IC-814 hijacking was not a standalone, but one of four millennium plots against the US, Jordan, Yemen and India. Two were disrupted, one miscarried, the Indian hijacking succeeded. Apparently, the Jordanians tipped off the others. The issue here is: was India in the loop?

At Kandahar the ISI, Taliban and Al Qaeda worked in tandem, with bin Laden supervising. The 26/11 attack saw the LeT agenda again overlapping with Al Qaeda’s, when US citizens and Jews were targeted. Ilyas Kashmiri’s journey from an Indian jail to his position as a possible successor to Osama reinforces the fact that Pakistan-based militancy is a single, monolithic monster.

The last chapters moot what Riedel terms the “unthinkable”—a jehadi general seizing leadership of Pakistan’s army in the future. Officers recruited during Zia’s presidency are now major-generals. A progeny of the Zia-Osama-Omar union controlling an army with nukes, particularly a bearded Mahdi-in-uniform spewing radical Islam, would be a nightmare for not just India but even China, Iran, the gcc states and the US. India has always asserted that closet Islamists already infest Rawalpindi—now borne out by Osama’s killing. The “unthinkable” may already be here.

Riedel advises the US not to alternate between engaging elected Pakistani governments and backslapping generals. He recommends transparency in US-Pakistan strategic discussions, probably impossible after the Osama episode. He then goes on to suggest that the resolution of the Kashmir issue is the sine qua non for Pakistan’s de-radicalisation. This is not much different from the Indian government’s reiteration that there is no option but to engage Pakistan.

Pakistani opinion polls, quoted by Riedel, indicate heightened religious piety but also greater opposition to terrorist targeting of civilians. The US must, he feels, engage Pakistan but with clear red lines, independently verifiable, on their counter-terrorism commitment. This was before Osama’s elimination.

The new red lines are bound to be more onerous. Surprisingly, Manmohan Singh, when quizzed in Kabul on Osama, fell short not only of the US reaction but even Nawaz Sharif’s demand for a judicial inquiry. While restraint is welcome, diffidence can be pernicious, especially on the critical point of who was supporting Osama.

While Riedel recognises Pakistani duplicity, for India he suggests compromising with a foe whose politicians either negotiate under the army’s duress or are simply schizophrenic. Riedel himself points out the schizophrenia. During Benazir Bhutto’s visit to Washington in 1995, for example, Riedel notes how while she whined to President Clinton about dark forces in league with ISI who were inimical to her in Pakistan, she was paradoxically “overseeing the rise of the next generation of jehadis in Afghanistan”. It was this same Taliban offshoot, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, and its associate, Al Qaeda, that assassinated her twelve years later.

Riedel’s book raises several red flags. And some remedies: Pakistan must unlock its “deadly embrace” with jehadis; the US must ration the carrots and oil the stick; India must calibrate its dialogue with cogent red lines on terror, while enhancing its engagement with Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia and confronting the “unthinkable”. These are some answers to Riedel’s riddle.