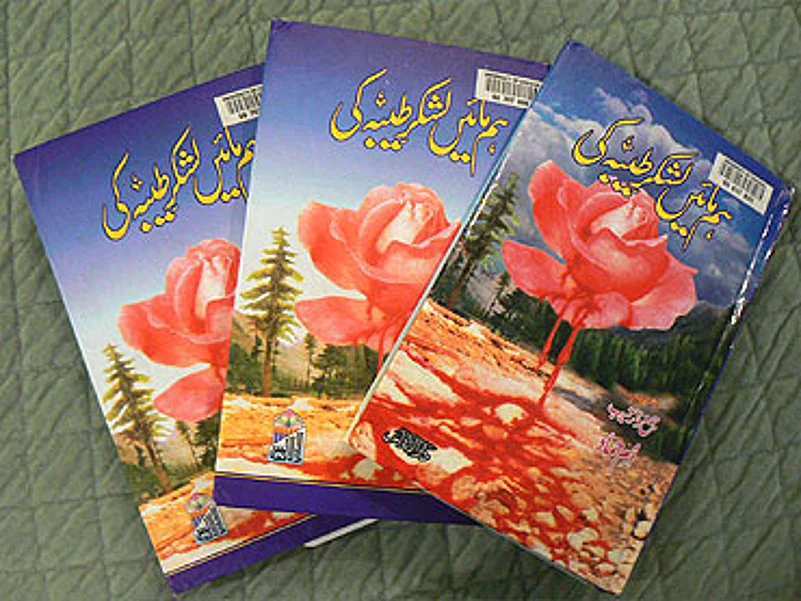

The book is titled Ham Ma’en Lashkar-e-Taiba Ki (‘We, the Mothersof Lashkar-e-Taiba’); its compiler styles herself Umm-e-Hammad; and it ispublished by Dar-al-Andulus, Lahore. Its three volumes have the same garishcover, showing a large pink rose, blood dripping from it, superimposed on alandscape of mountains and pine trees The first volume, running to 381 pages,originally came out in November 1998, and was reprinted in April 2001. Thesecond and third volumes, with 377 and 262 pages, respectively, came out inOctober 2003. Each printing consisted of 1100 copies. Portions of thebook—perhaps much of it—also appeared in the Lashkar’s journal, MujallaAl-Da’wa.

Here is how the publisher, Muhammad Ramzan Asari, describes the book’scontents and purpose.

The book at hand, Ham Ma’en Lashkar-e Taiba Ki, is a distillation ofthe tireless labor and far-flung travels of our respected Apa (‘Elder Sister’), Umm-e-Hammad, who is in-charge of the Lashkar’s Womensection, and also happens to be an Umm-e-Shahidain (‘Mother of Two martyrs’)…. [I could be misreading the text, for I foundno reference to any of her sons except one, whom she described as a very muchalive mujahid.] Her poems are on the lips of the mujahdin. Numerous young menread or heard her poems and, consequently, set out to perform jihad, many ofthem gaining Paradise…. Our workers should make this book a part of thereadings for the ladies at homes to awaken the fervour for jihad in the breastsof our mothers and sisters. (I.13.)

In her preface, Umm-e Hammad describes her own conversion to the cause atsome length.

Once I was among those who considered jihad the root of big trouble [fasad],and vociferously called it that. I hated the Markaz. I considered it to be theden of a gang that lured innocent boys away from their homes and schools only tothrow them into the inferno of battle in Kashmir, making them a sacrifice to itsown end of collecting Riyals and Dollars from foreign sources. Then I noticedthat my husband, Asif Ali, whose organizational name is Abu Hammad, had growncloser to Hafiz Muhammad Sa’eed Sahib. He had known the latter fairly well formany years, but now he would often remark at home: ‘I’m raising my childrenwith prohibited money because I work in a bank.’ I immediately knew thatsomething was not right. Realizing that the man had fallen into the clutches ofthe so-called ‘saviours’ of Kashmir, I quickly took some counter-steps toprotect my family. I took every loan offered by the bank to make the man’sburden of debt heavier. In brief, there was Abu Hammad, suffering because hefelt he was earning an illegitimate living, and there was I, ensuring my owncomfortable future by adding to the load he carried. I would constantly tellhim, ‘We eat of only what we actually earn. We work hard. We meet ourduties.’ But, while Satan helped me find arguments and excuses, Allah, theAlmighty, was determined to open the doors of His help and guidance to one ofhis guileless, well-intending servants. And so, one morning that simple man lefthome for the bank as usual, and handed in his resignation. On the way out of thebank, he paused at the threshold and vowed never to cross it again. He then wentto the Markaz, and from there proceeded directly to Afghanistan, to the veryfirst training centre of the Lashkar at Jaji.

It was as if some monstrous calamity had hit the family. There was no abusethat I didn’t throw at the Markaz and its director, and no crime I didn’tcharge them with. Still dissatisfied, I consulted with the family, obtained theaddress from Hafiz Muhammad Sa’eed Sahib, and showering curses on that ‘gangof frauds’ went to the Muzaffarabad office of the Markaz.

What I did theremust have pleased Satan a great deal. May Allah forgive my sin.But after I had seen how the mujahidin lived—their hard training, their fervour, their deep faith—I soon began to examine my own ugly past, when I hadlived as if I were blind, deaf, and mute. A deeply humiliating sense of remorsecame over me. I listened to the lectures given by the teachers at the Markaz,and realized that I had been totally ignorant of Jihad fi Sabil-allah (‘Jihad in God’s Path’), which endows any Muslim with all the dignity andpower in the world. I asked myself: how is it that Muslims everywhere arevictimized by infidels? Why are they brutalized and humiliated despite theprayers, fasts and pilgrimages they perform? I now turned to the Qur’an. Iread Surah Anfal (chapter 8), Surah Tauba (chapter 9), and otherverses on jihad; I listened to discourses on these verses; and I came face toface with that resplendent aspect of Islam which in our history recalls themothers of Salahuddin Ayubi, Tariq bin Ziyad, Muhammad bin Qasism, and Mahmud ofGhazna. All praise to Allah, for His great kindness. That was the first miracleof that journey in jihad. Our hearts were transformed…. May the Almightyforgive us the nineteen years of disobedience—our eating the bread of usuryfrom the bank….

In a second introductory note, Umm-e Hammad throws some light on the genesisof her book and of the Lashkar. The group, according to her, started itsmilitant activities at Jaji, in Afghanistan, where it joined hands with theSalafi Afghans of Nuristan in their battle against the Soviet forces. (In thebook itself, several ‘martyrs’ are described to have received militarytraining and seen action in Afghanistan. In one account the future ‘martyr’even describes how the Arab mujahidin made fun of the Pakistanis fighting besidethem.) Subsequently, the Lashkar entered the Kashmir valley, with ‘less than700 mujahidin ranged against 700,000 satanic forces.’

After a rhapsodic paean to the mujahidin’s alleged successes, Umm-e-Hammadcontinues:

Then the wielder of this broken pen noticed that the mothers and sisters,whose hopes and desires, dreams and wishes, provide the blood that colors theshattered bodies of the Lashkar mujahidin, live in purdah [and can’t be seen].And so this humble woman, considering it a duty to unveil [their feelings],presented the idea to Hafiz Muhammad Sa’eed Sahib, the Amir of theMarkaz, who strongly encouraged me. A few days later, Zakiur Rahman Lakhwi, the Amir of the Lashkar, and Abdur Rahman Al-Dakhil, the Amir of the OccupiedValley, set out to meet with the families of the martyrs who lived in Punjab.When my son Hammadur Rahman learned about it he decided to be my mahram—[legitimatemale companion]—and obtained the permission from [Hafiz Sa’eed]. [On 16December 1995] our group set out for its first meeting, with the mother of the Shahid Imran Majeed Butt of Faisalabad…. After collecting theblood-drenched words and the stars-like sentiments of the mothers and sisters ofmore than one hundred martyrs of the Lashkar, our caravan returned home onJanuary 11 1996. (I.19.)

Subsequently, Umm-e-Hammad travelled to Karachi and parts of Sindh in asimilar manner. Again, while the men talked with the male members of thefamilies, she met with the women to take down their recollections of their‘martyr’ sons or brothers. Chiefly the book is based on her notes, but onoccasion she fills in gaps from the files of the Lashkar’s journal, MujallaAl-Da’wa.

While the first volume of the book was clearly compiled by Umm-e Hammad, thetwo subsequent volumes, while carrying her name, seem to be the work of maleparty hacks. Particularly the third volume for it badly lacks all the littlepersonal touches that Umm-e Hammad adds to the stories in the first volume; muchof it simply brings together the overblown prose that first appeared in the Mujalla.

The first volume of the book describes 81 ‘martyrs’, the second 58, andthe third 45. Taking into account a few repetitions and unlisted additions, therough total of comes to 184. In this small sample—the Lashkar claims to havesacrificed many times as many—most of the families appear to be rural and notterribly well-off, and most of the ‘martyrs’ seem to have been in theirearly twenties or less. Most of them seem to have studied only up to thesecondary or matriculation level. Only a few went to a madrassa.

Each chapter of the book consists of two parts. The first, longer, sectiondelineates the life and character of the ‘martyr’, mostly through the wordsof his mother and sister, though comments from the male members of the familyare not necessarily left out. Here we learn about the youth’s background, hisfamily and his neighbourhood, his life before and after the ‘conversion,’ending frequently with some details of his death. The second, shorter, sectionpresents the ‘last testament’ sent home by the ‘martyr’. Stiffly formaland predictably formulaic, these statements nevertheless often reveal quite abit about the individual mortal behind the generic ‘martyr’.

Below I give a reasonably fair translation of one complete entry from VolumeI. It is quite representative of the others in tone and narration, except forone feature: the ‘martyr’ does not have a jihadi name in addition to hisown. (More on names later.)

***

The Martyr Imran Abdul Majeed [Butt], May Allah’sGrace be upon him.

In the two-storied house in the neighbourhood called Khalidabad in the city ofFaisalabad, there is a room on the ground floor. It contains a bed, a table, anda chair. A pile of jihadi books and copies of the Mujalla lies on the table, also some‘stickers’ inscribed with jihadi expressions and Qur’anic verses. There is an armoire filled with the Shahid Imran’s clothes and other possessions. This room is now the only abode of hisparents. His mother says, ‘I sleep here, and I also say my prayers here.It’s here that my heart finds comfort.’

The Shahid Imran Majeed was older to his four sisters. There is alsoanother brother, younger to the sisters. Imran’s mother is a college graduate.She is sober, patient, and uncomplaining. Lost in the memories of her son, shetold us:

‘Imran always dressed well. He was also sober and refined. He would ask fornice clothes and pullovers, and make a point to get them. Not one to spend muchtime with friends, he was, however, very fond of cricket, and an all-rounderplayer himself. He was invited to every tournament, and always took greatinterest in them, playing with one team here then captaining another team someplace else.

‘He was also a fine student. He studied hard, and got his B.A. degree withdistinction. Then he started preparing for the ‘CSS’ examination. Hisrelatives have muchinfluence in Faisalabad. Imran got some nice job offers, and importantpeople were willing to recommend him, but Imran declined. He wanted somethingmuch better.

‘Then a cricket match was announced between India and Pakistan. Imran saidto me, "Ammijan, you must buy me a TV. I’ve got to see the match." We haveseveral relatives living nearby. I told Imran to go and see the match with them,but he kept insisting.

He wanted to watch the match on his own set. Soeventually, we got him a set.Whenever there was a match between India andPakistan, Imran would be so impassioned you’d think a war was about tostart.’As I listened to her, I realized that Imran had felt nothing but hatred forthe enemies of Islam, but it found its true expression much later. He watchedcricket matches to relieve himself of that hatred, and eventually God directedhis feelings on to the paths of Truth and Honesty. Who knows how many young menthere are who vent their disgust and hatred for India through these cricketmatches? They would discover the path of jihad if only someone correctly guidedthem and their hatred. The storms raging in their breasts would sweep away allthe Indian boasts like so much rubbish. But I digress. We were talking aboutImran Majeed.

By now his three sisters had also joined us. The older sister described to mehow Imran changed after finishing his B.A. Maulana Irshadul Haq, the Imam/Khatibof the nearby mosque, would often say to the congregation: ‘There is a boyhere whose devotion and fervour when he prays makes me very happy.’ It was inthe Maulana’s company that Imran obtained his jihad consciousness. [DuringRamadan,] when Imran would lead the taravih prayers at home, his sisters would often exclaim, ‘Mani Bhai, you make usstand too long in the prayers. We get tired.’ But Imran would only smile andsay nothing.

Imran’s thinking had started down the path of jihad. Now there was only onestep left to take. He asked his mother to let him go for the initial training oftwenty-one days, and left for the Lashkar’s camp when she agreed. From thecamp he wrote a detailed letter. The spiritual refinement and firm faith heobtained there enriched him so much that now he was bent upon destroying thesame TV set he had earlier insisted on buying. Faith is miraculous; when itfinds its way into someone’s heart, his breast shines with purity, his eyessee beyond this small world, and his thinking reaches the ultimate heights ofaction. Imran Majeed now demanded that the TV set should be smashed to bits, forAllah had now put the strength in his arms to pick up a gun, to enter thebattlefield and destroy those who rejected Allah. That instrument of falsedelight now disgusted him. Blood ran faster in his veins, and his falcon spiritwas ready to pounce upon its prey.

When Imran returned home, everyone was amazed: his face was adorned with theProphet’s sunnah. The family asked him, ‘Is it for good, or just seasonal?You won’t shave it off a few days later, will you?’ But his decision waspermanent. Then one day, Imran disclosed to his mother his intention of going toAfghanistan and taking part in the jihad. His mother became very upset. She hadwatched the revolutionary change happening in him, and knew what to expect. Butshe quickly recovered, and said to Imran, ‘The road you have chosen foryourself is glorious, but I too have my responsibilities, and they hold meback.’

Imran had a tender heart; he couldn’t bear to give the slightest pain tohis mother, and so he fell silent. But he would often talk about jihad and itsimportance, and the great rewards that followed from it. Imran’s mother toldus, ‘I always told him to raise his voice against tyranny and injustice. I toohate injustice.’

Then Imran Majeed went off to Afghanistan, and joined the Afghan jihad. Hewould return once in a while, stay with the family a few days then againdisappear. The family never learned about the places he visited, except for hismother’s sister Safia, who is the headmistress at the Government High Schoolat Barki.

She was Imran’s confidante; she also continuously encouraged him.Imran’s mother had some idea of what Imran was heading toward. She tried todissuade him, but only indirectly. She said to him, ‘Imran, you have foursisters. They are growing up. You should first fulfil your responsibilitytoward them. Once you have done that you may devote yourself to jihad.’ Imranwould mostly remain silent, but if she persisted, he would say, ‘Ammi, yourdaughters live within the walls of your house—in peace and safety. Ourrelatives live nearby. And yet you worry about them so. Shouldn’t you alsothink of those "daughters" who are surrounded by enemies, who are inharm’s way and waiting for us to help them?’ His mother couldn’t give himany reply, for her heart told her he was right.

Imran was trained in Communication and Action, as well as in other branches.A fast learner, he soon became an expert in every wireless technique. In fact,that was the reason he was selected to go into the Valley. In those days themujahidin in the Valley couldn’t easily communicate with each other, and badlyneeded an expert’s help. And so Imran was chosen. As in cricket earlier, injihad too he proved himself to be an all-rounder.

When, before going into the Valley, Imran came home to see his family, heappeared silent and withdrawn, and not relaxed and playful as he used to. In hismother’s words: ‘It seemed that all the sorrows of the Kashmiri victims hadpermeated his soul, and he had deliberately made himself indifferent to any kindof affection and happiness. That is how he was when he submitted his life toAllah.’

I then remembered what had happened when, only two or three days afterImran’s martyrdom, we had gone, with Imran’s aunt, Umm-e-Talha, and otherwomen, to meet with Imran’s mother at Faisalabad. That day, when food wasserved, Imran’s mother invited us all to start by saying, ‘Please begin.It’s Imran’s walima [wedding] feast.’ We stared at her in amazement, but she calmly uttered ‘Bismillah’and began eating. We had to follow her example. Now when I heard her remarks Irealized that Allah had set aside special abodes in eternity exclusively forpeople like her, so accepting and so totally reconciled to His Will.

Besides Imran’s mother, his sisters, his father, and above all his AuntSafia are worth all praise. The latter continuously encouraged him, and gave himmuch help. Then she improved the minds of his mother and sisters, and made themunderstand how superior Imran’s feelings and intentions were. Even now, afterImran’s martyrdom, she remains devoted to jihad, and whole-heartedly helps themujahidin with money and with prayers. May Almighty Allah reward her greatly.May He make her a rightful claimant to the promised, unfailing intercession bythe martyr on the Day of Judgment. Amen.

Imran Shaheed’s mother put her feelings into verse too. One can see in herpoem an effective blend of Imran’s memory and her own feelings for jihad.Consider here only her emotions. Ignore the matter of artistic worth; consideronly what her heart felt.