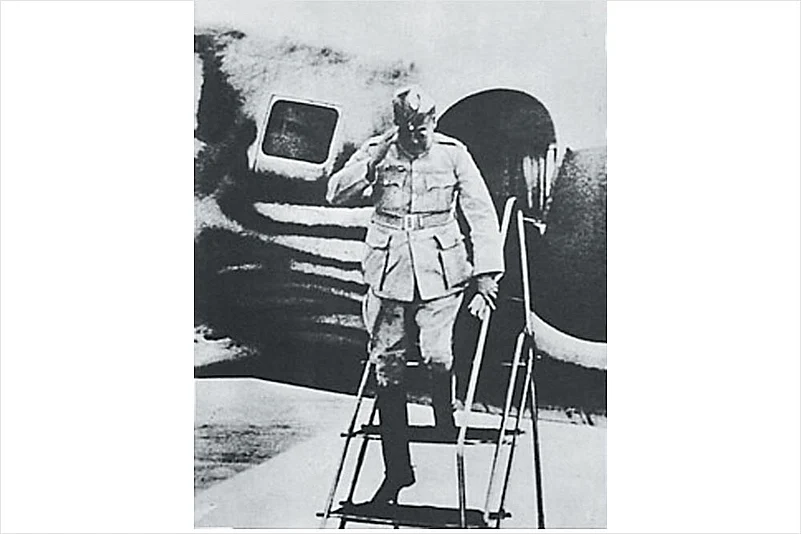

One of the great ‘mysteries’ of independent India—the ultimate fate of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose—has gainfully employed hordes of pamphleteers and conspiracy theorists. Others have had as their sole avocation the imbibing, exchange and dissemination of rumour. In Laid To Rest, Ashis Ray has gone deep into the files of the Shah Nawaz (1956) and Khosla (1974) Commissions as well as seven other independent probes, and interviewed primary eye-witnesses over 30 years to arrive at what is the obvious conclusion—that Netaji lost his life in a plane crash on August 18, 1945 at Taihoku (Taipei City).

But how did the truth, borne aloft by so many witnesses, face such a barrage of incredulity for so long? Its roots lie in Bose’s brother, the Congress leader Sarat Chandra Bose, who had at first come to terms with his beloved brother’s death. Yet, goaded by family-members and others who had pecuniary and political gains in sight, clinging on to a straw of hope (Bose’s death was announced in 1942 by the colonial government, only to be disproved by the man himself), he came to take a staunchly sceptical line. Then, with the deterioration of his relations with old colleagues Nehru and Patel, an unfortunate silence descended on the matter. “Neither is known to have shared...three British intelligence reports (two in 1945 and another in 1946) with Sarat....,” writes Ray. Blinded by his obfuscatory coterie, Sarat Chandra didn’t even believe Col Habibur Rehman, Netaji’s aide de camp and a survivor of the crash, even after he personally narrated to him what transpired at the Matsuyama aerodrome. Nor did he visit Japan and Taiwan, where other survivors of the crash lived. With Sarat Chandra’s death in 1950, his doubt hardened into the self-indulgent cult of Netaji we have grown up with. The Centre’s odd silences—surely, a villain of the tragic piece—didn’t stop here. Japan’s interim and final reports (the latter in 1956), the Taiwanese inquest (also in ’56) and the gathering of material by Japan’s Yomiuri Shimbun daily in 1966—all of which supported the crash—were also not brought into the public domain. It is inexplicable why.

Ray devotes a chapter to the various ‘cock and bull’ stories about Netaji. The charade over Faizabad’s Gumnami Baba was emphatically discredited by a DNA mismatch, while to disprove a ‘sighting’ from Hanoi, he pored into the French state archives. The other major theory, that Bose crossed into, was incarcerated and later died in Siberia, USSR (surely his intended destination, via Dairen in Manchuria) is also disproved by emphatic Russian answers—denials of Netaji’s presence ever in the USSR—to the Centre’s queries in 1991 and 1995.

One purpose of Ray’s book is to end ungainly speculation over Bose’s death, and he provides a minutely detailed narrative of the last journey by air, the crash, Bose’s death, cremation and the journey of his ashes to Tokyo. Each bit of the narrative is held, as it were, under the microscope of multiple witness accounts. The dense mesh of such cross-checking could have been tiresome to plough through, yet, the simple string of events, reflected through the many subjective mirrors, and refracted only by minor discrepancies, holds the reader in fascination.

But why have the ashes of a great Indian patriot—proven to be his through irrefutable ‘logic’—lying at Tokyo’s Renkoji temple, never been brought back to India? Ray informs that in 1994, the issue was referred by the PMO to the Union home ministry. The IB, however, shot it down, citing low interest, and betraying a fear of possible public outrage in Bengal. Furthermore, the MEA suggested the “creation of a favourable public opinion” before any action.

Ray is no passive accumulator of facts. With the aim repatriating Netaji’s ashes as a fitting tribute on his birth centenary in 1997, he initiated a move by involving all stakeholders. Armed with the fruits of his own research, he wrote to all top leaders, including PM Narasimha Rao. He also had a plan to rope in the intransigent Forward Bloc (the party which Netaji founded and which claim his legacy militantly). It bore partial fruition, before the Home Ministry again recommended the “maintenance of status quo”. These “weak and faint-hearted” responses show how the mulishly baseless stand of the Bloc and some of the Boses successfully conveyed a sense that they speak for a majority of Netaji’s admirers (an arrant lie).

Laid To Rest should silence some of the addled foghorns, and is a testimony to Ray’s deep commitment to that cause. Therefore, it’s surprising to see his continual, grovelling declarations of not claiming ‘publicity’ or ‘credit’ for his salutary role, especially in the matter of bringing Netaji's ashes home. The credit for his hard labour is his to claim.