Binayak Sen doesn’t take kindly to hero worship. When Minnie Vaid, a documentary film-maker, first hears of the now celebrated doctor jailed for sedition, she throws up her corporate job and goes in hot pursuit of her new idol. She wants to write a book and make a film on him, she tells Dr Sen. But to her dismay, the doctor refuses to cooperate. He’s just a symbol of what’s going wrong in the country, Sen tries to explain, “it has nothing to do with my personal qualities”. But the star-struck Vaid can’t be dissuaded, either by his stern silences or his snubs. Eventually, they hit on a compromise: Sen gives her a list of half-a-dozen friends and “close associates” she can interview. Thus begins Vaid’s breathless journey, stretching from the prestigious Christian Medical College in Vellore, from where Sen graduated in the ’60s, to remote villages deep in the forests of Chhattisgarh, where he ran his crowded clinics, to discover the man behind the celebrity.

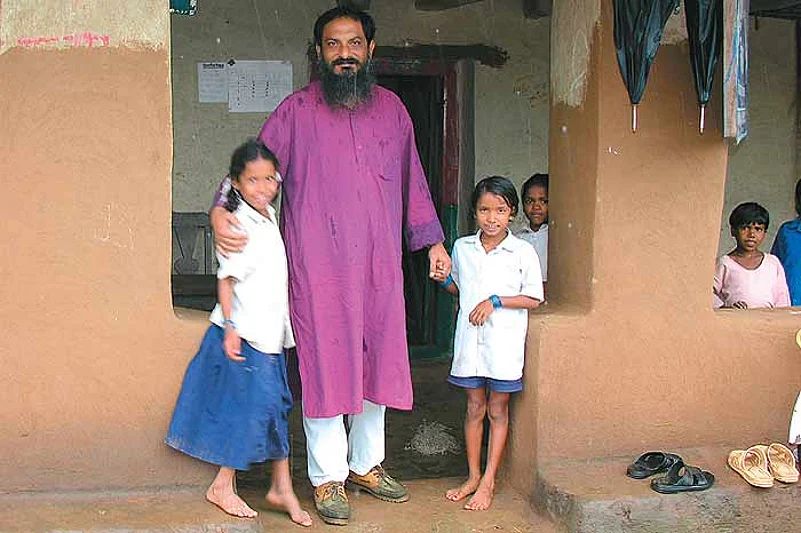

Wherever Vaid travels, Sen’s name works like magic: doors are thrown open, stringcots dragged out, and Vaid is plied with tea and food as villagers readily share their stories about their doctor—how he saved their children’s lives, helped them start a self-help women’s group, guided them during a famine or to start organic farming. “I have never seen a man like him,” Ghasiya Ram, a health worker whom Sen trained from scratch, tells Vaid. “He goes to each person’s house, asks them about their difficulties, attends to patients in their homes and, at times, even arranges food for them.”

We get a sense of the villagers’ outrage, that a man as good as their doctor, who “would sit on the floor and eat with us”, should be slammed into jail. They tried to visit him in jail, and when they were stopped by the police, turned out in large numbers at the protest rally when his case was being heard in Raipur.

But the people that Sen suggests Vaid meet are no random list of friends. We soon realise what he’s trying to do: gently guide his would-be biographer into discovering the appaling human rights abuses going on in Chhattisgarh, whether it is the displacement of thousands from their villages in order to vacate the land for the big mining companies or the state’s refusal to provide healthcare and schools for the displaced. In her single-minded pursuit of Sen’s story, Vaid can’t help but give us a fleeting glimpse of the condition in which villagers live. One woman who had lost her husband and burnt her hands in a stove burst, for instance, had to walk 110 km for 15 days to reach a doctor. By then, there were insects crawling out of her hands and the doctor said she would have lost both her hands if she had come even a week later. But Vaid quickly turns this horror story into a pat on Sen’s back for showing moral courage and compassion under trying conditions.

It’s not difficult for Vaid to coax personal stories about Binayak from his associates. Yogesh Jain, an aiims-trained doctor inspired by Sen to throw away a good life in the city to run a hospital for tribals, recounts a particularly insightful episode. Once, while travelling on a train, Sen was mistaken for a maulvi because of his long beard. Jain then asked Sen why he insisted on growing a beard. “Because I want to see what it means to be insecure, to know how it feels to be a minority in one’s own country.”

It’s this refusal to care about consequences that Jain admires most about Sen. “Binayak is that rare doctor who looks at root causes, links ill-health to politics, to unequal distribution of resources, whether it is water, food, money or healthcare services. Health work of this kind is a political act and he goes ahead, not caring about consequences. I can’t do it myself but I would support someone who does,” Jain tells the author. “I would tell him how scared we all were for him and he’d say: ‘Yogesh, I can’t stop doing this, there’s no other way.’”

Till the end, the biographer and her subject remain at odds: Vaid determined to focus on his personal story, while Sen is equally stubborn that his story is Everyman’s. Whether it is his healthcare services or his years in prison, Sen is steadfast in his refusal to personalise his story. One can see why. So long as we insist, like Vaid, in valourising Sen, we can pretend that we aren’t faced with his choices: to either resist injustice or perish.