The resounding success of the Indian space programme, particularly the lunar mission, Chandrayaan, and the Mars Orbiter Mission in recent years, has made the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) a household name. After every successful launch, stories about the ‘humble’ beginnings of India’s foray into space are written, accompanied invariably with a picture of a man cycling around with a rocket cone on the carrier in the Thumba rocket launching station in Kerala. That cycling man is rocket scientist C.R. Sathya, and it was shot by the great Henri Cartier-Bresson in the formative years of the Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station (TERLS). The only mode of moving around the vast range then was by cycle, and rocket parts were carried on cycles or bullock carts, as revealed in this book by pioneering space scientist Ramabhadran Aravamudan, along with his journalist-wife Gita Aravamudan.

Another picture that went viral around the time A.P.J. Abdul Kalam became president shows him crouched on the floor, trying to fix a rocket payload with another colleague, who is shirtless. This picture was also shot by Cartier-Bresson in the church building from where TERLS labs operated, and the man in vests is Aravamudan. “We had no fans, let alone air-conditioning. It was so unbearably hot that I had removed my shirt. Kalam was getting anxious as the wretched payload unit would not sit properly.... Neither of us bothered about the old man with the camera who had wandered in....,” Aravamudan recalls in the book. Someone like Aravamudan, who was handpicked by Vikram Sarabhai even before Thumba became a rocket launching site, is clearly well placed to tell such stories. The personal history of ISRO penned by this great scientist takes readers on a gripping journey of India’s space programme from day one in 1962, when ISRO was just a spark in the mind of Sarabhai.

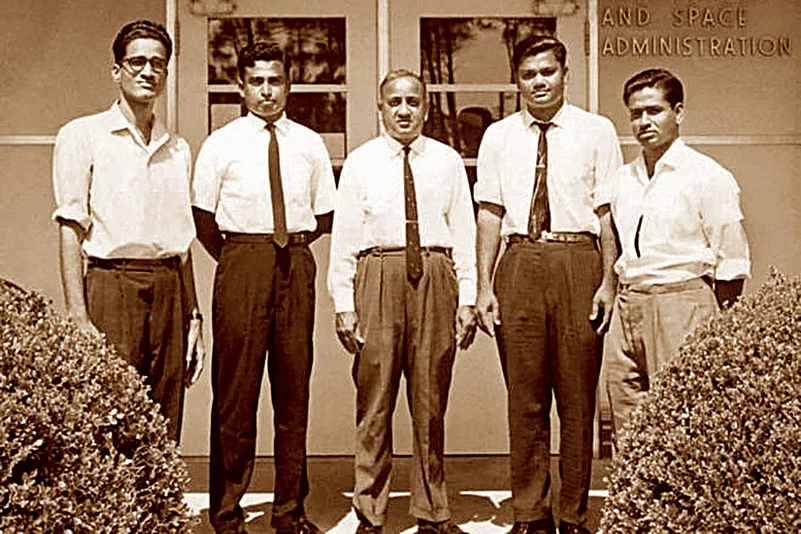

The book is revelatory on many counts. For instance, very little was known about help from foreign space agencies like NASA in the initial years, except that the Nike Apache rockets launched from ThuMBA came from the American space agency. While there was no formal transfer of knowhow for design, engineering, telemetry and propellant making, information flowed through personal visits, training and equipment which was loaned or gifted. Aravamudan’s training started with a visit to some facilities of NASA, along with three other young engineers. Kalam later joined the group. The group of young recruits participated in fabrication and testing of radar and telemetry ground station, which was later shipped to Thumba. Since Thumba was declared as a UN facility for sounding rocket experiments, it attracted scientists from space agencies from the USSR, France, Germany, Japan and so on. Knowing well that he was entering an area of endeavour in which India had little expertise, Sarabhai made aggressive attempts to attract talented Indians from America and elsewhere. Advertisements were placed in foreign newspapers and journals for NRI engineers and scientists. The first lot, at the Physical Research Laboratory (the cradle of the space programme) in the 1950s, all came from America—E.V. Chitnis, P.D. Bhavsar, S.R. Thakore, Vasant Gowarikar, Muthunayagam and others. After ISRO became a separate entity in 1969, Sarabhai dispatched Aravamudan, Ramakrishna Rao and Y.J. Rao on a world tour of all major space agencies. By now, the space programme had moved from sounding rockets to the next stage—planning for launch vehicles and satellites as well as a launching station at Sriharikota. The book has detailed the experience of this familiarisation trip, which covered major facilities of NASA, the European Space Agency and aerospace companies like Rolls Royce: “It all looked almost like science fiction to us then. We never imagined we would ever have anything like that in India.”

Aravamudan has successfully conveyed the excitement, twists and turns, successes and failures associated with maturing of the space programme from sounding rockets to inter-planetary missions. In doing so, the author has not glossed over sensitive or unpleasant matters, such as Sarabhai’s troubled marriage or the infamous ISRO spy scandal. Overall, the book is a nice exposition of the space programme and provides an insight into the ‘ISRO Way’ of executing large and technologically challenging projects. It has more value since it comes from the man who has seen it and done it all. The book, written in a lucid and accessible style, is a welcome addition to the small but growing literature on India’s space programme and on the development of science in the post-independence period.