In Franz Kafka’s The Trial, when Josef K. finds himself arrested, he is unable to figure out what is he accused of. Clueless and ensnared in the labyrinths of a serpentine legal structure, he keeps on doing the things that make him look guilty. Ergo, it is decided that he must be guilty and he is executed. “For Josef K.,” writes Kafka, “the proceedings gradually merge into the judgment.”

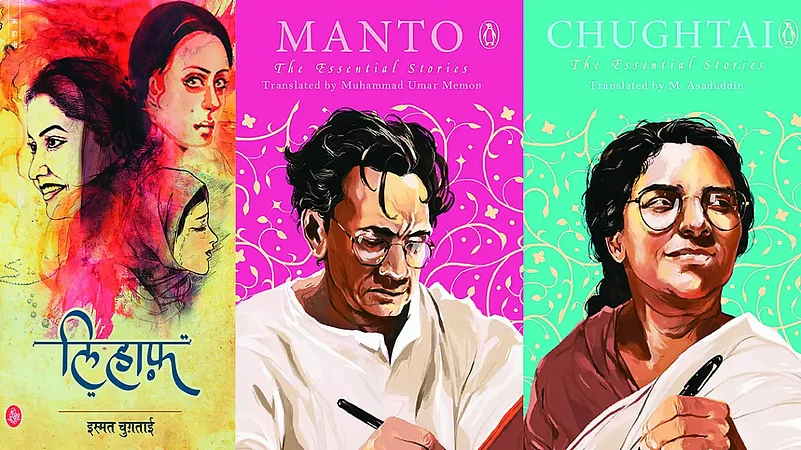

Born in Ludhiana, Saadat Hasan Manto was among the most controversial Urdu writers of the 20th century—partly because his fiction stirred the horizons of his times, and chiefly because he was tried for “obscenity” in his fiction several times. Many of his short stories, often dealing with themes of Partition, violence and sexuality, dragged him into acerbic courtroom battles, and like Josef K., he beheld the horrors of the State from close quarters.

“A court is a place where every humiliation is inflicted, and where it must be suffered in silence,” writes Manto about his fifth trial, when in 1952, a Karachi magistrate judged his Upar, Neechay aur Darmiyan to be obscene. “I pray that nobody has to go to the place we call a court of law,” he writes in The Fifth Trial, “I’ve seen no place more bizarre.” Manto’s short stories were banned thrice in the colonial era, and thrice afterwards, in Pakistan.

Although his fiction bore the allegations of being obscene and was on many occasions tried, his short story Bu (Smell) invited the attention of the intolerant British colonial masters because they found references to the Women’s Auxiliary Corps (WAC) unsettling. The WAC (India), which comprised both Indian and European women, was established in 1942 to release officers and male corps from sedentary posts during World War II, so that they could serve with active units. Bu tells the story of a man called Randheer who lives in Bombay. One day, as the monsoon rains pour down raucously, Randheer sees a tribal woman from his balcony, seeking shelter under a tree. Randheer had been feeling lonely for a while as “the War was on, and most of the Christian girls of Bombay who were easily available in the past had joined the WAC.” The man calls the tribal woman up to his flat and the story progresses with a detailed narration of their sexual encounter.

Although the short story was tried for being obscene, the Britishers were irked solely because of the mention of the WAC in the story. In her book, Hidden Histories of Pakistan, Sarah Fatima Waheed mentions a memo dated May 29, 1944, in which General Wade notes, “The story (Bu) is certainly most detrimental to recruiting, insofar as it suggests that association in the WAC may be those of prostitutes and we wish to press for prosecution.” Given the immediate political context of strikes, especially during the Quit India Movement, mass demonstrations and popular rebellions against core institutions of imperial life, including the military, and references to WAC in the short story, had deeply annoyed the War Department of the British Indian Army. “The person,” writes Waheed, “who first brought the story to the attention of British officials was M.K. Khan, the Honorary Secretary of the Indian Christian War Bureau.”

Surprisingly, Ismat Chughtai, an Urdu novelist, short story writer and Manto’s contemporary and friend, was simultaneously being charged for her short story, Lihaf (Quilt). Chughtai’s story was also facing the charges of being obscene for explicitly exploring the themes of female homoeroticism and homosexuality.

In her autobiography, Kaghazi Hai Pairahan, Chughtai recalls while she was traveling to Lahore for the trial, she stayed with Aslam Saheb, a writer and an acquaintance of her husband. Aslam alleged that her stories were “filthy” and told her to apologise in court. This had made Chughtai furious. “I retaliated like a woman possessed,” writes Chughtai.

When she pointed out that Aslam’s stories were obscene too, and asked him why he wrote them, he proudly retorts: “My case is different. I’m a man!” That’s when Chughtai scathingly told him, “You have the freedom to write whatever you want. You don’t need my permission. Similarly, I don’t feel any need to seek your permission for writing the way I want to.”

Chughtai’s persona was as unabashed as her stories—sharp, yet truest in form. She took the world head-on and in her stories, fought the oppression she saw women going through. She spent her early childhood “freely” and would play football, hockey and gilli danda with boys, including her many brothers. “The real culprits,” Chughtai writes in one of her essays, “were my brothers. It was their company that enabled me to think freely.” It was only when their family moved to Agra after her father’s retirement that she realised being a woman comes at a cost. Contrary to her earlier days, she found the new atmosphere “stifling, and oppressive”. “The washerwoman was beaten every night,” she writes, “the sweeperess received a walloping from her husband every other day, and in the adjacent neighbourhoods, husbands often thrashed their wives”.

Chughtai always fought against the stereotypes into which women were being relentlessly fitted in. As a young girl, she once convinced her father to excuse her from learning how to cook, and asked him to facilitate her education instead. “Women cook food, Ismat! When you go to your in-laws, what will you feed them?” Chughtai recalls her father asking her one day. “If my husband is poor,” Chughtai tells him, “then we will make khichdi and eat it. If he is rich, we will hire a cook”.

Afraid of being caught and punished, Chughtai tore up many of her stories during her youthful days. Once, her elder brother Shamim came into her room and found the manuscript of a story. Reading it, he wondered how she could write such “filthy stuff”. Luckily, no one took the brother’s “allegations” seriously because of his lying habits. It would have been the first-ever trial Chughtai would face for her writing—not in a courtroom, but within the walls of her very home. Many years later, when she was facing trial for Lihaf, the judge called her into the court anteroom and told her that he had read most of her stories.

“Your stories are not obscene. Neither is Lihaf,” the judge told her, “but Manto’s writings are littered with filth.”

“The world is also littered with filth,” she said.

“Is it necessary to rake it up, then?”

“If it is raked up, it becomes visible and people feel the need to clean it up,” Chughtai quipped.

That day, in the anteroom that would become immortal in the years to come, Chughtai dauntingly defended the liberty of literature and took the side of her friend Manto. To Chughtai, Manto was not just a literary figure. He was an influence, talking to whom, as Chughtai would often say, sharpened her sensibilities. “Having an argument with him was like sharpening one’s intellect,” writes Chughtai, “it was as if the cobwebs were being cleared, the brain swept clean with a jhadu.”

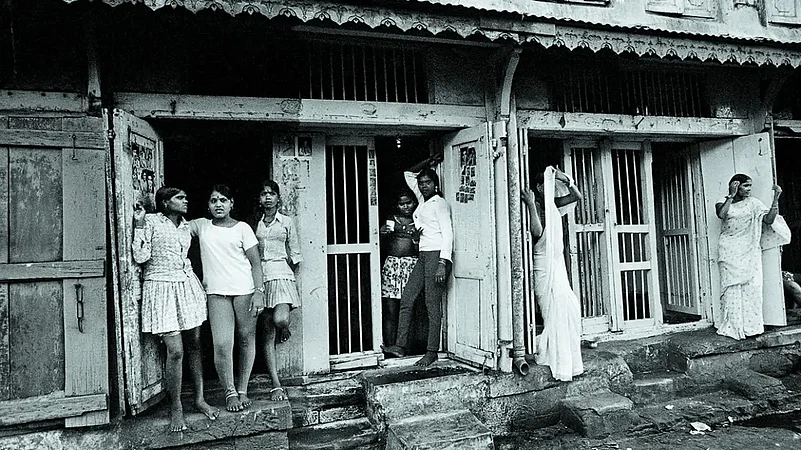

Manto’s sensibilities are reflected in his fiction, which, in more ways than one, was inspired by the woes that befell the subcontinent after the Partition—violence, bloodshed, rape and communalism. “India was taken, when it was at the point of Independence, and dragged into this enormous, dark pit,” he writes about the aftermath of Partition. He also wrote unabashedly, with poise and grit, on sex, desire, prostitutes, murderers and drunkards, without condemning anyone. No wonder that he found himself in the middle of a moral slaughterhouse, where everyone, even at times his friends, condemned him.

Mohammad Tufail, editor and publisher of the reputed literary journal Naqoosh, where Manto would often publish stories, had once published an essay titled Mr. Manto. The contents of the essay were so intimate, personal and prying that Manto, after reading the essay, was left depressed. “No man is without his weaknesses, but why put them on display?” Manto wrote in an essay, “…what’s the point of such revelation, when it brings the writer into disgrace?”

In the last phase of his life, Manto fell victim to the very demon he was fighting with his pen—the moral hypocrisy of the upper class. He was not always loose with the booze, but with a plethora of afflictions—the excruciating trials, death of his infant child and being the bull’s eye for the mudslinging and character assassination—he was transformed, says his daughter Nuzhat, “from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.”

On the night that turned out to be his last, he fell terribly sick, asking for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital. His family obliged. On his way to the hospital, Manto breathed his last, and left behind a treasure of stunning short stories—some heart-breaking, some stifling, and some still “obscene”.

Chughtai, on Manto’s death, had said: “Those who die, inflict a wound that neither aches nor bleeds; it just smoulders quietly forever.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "Quilt, Smell and the Trials")