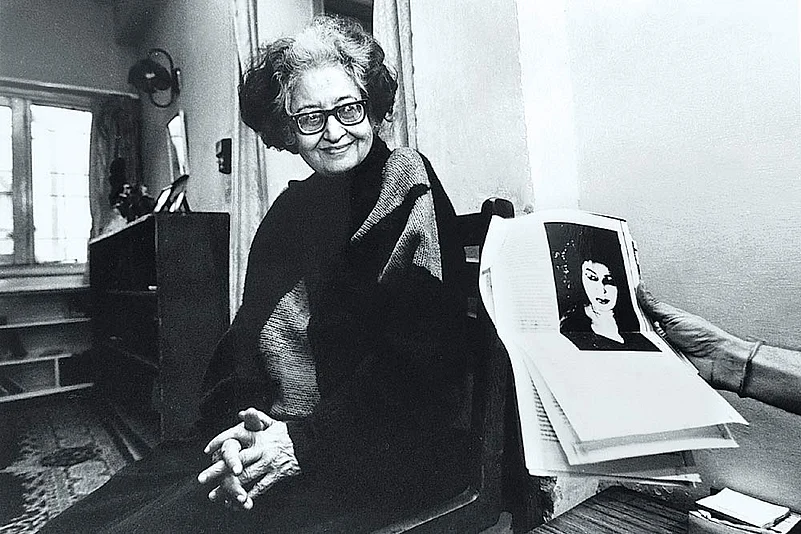

She was a bit of a mystery wrapped in an enigma. With her flaming orange mop of hair and fire-engine red lips, she was reticent, almost monosyllabic in public, preferring her pen to speak volumes, while maintaining a prickly silence, broken by a few short but sharp utterances when called upon to speak. One of the finest prose stylists of modern times, the author of dozens of books, almost all runaway best-sellers, bilingual and cosmopolitan to an extent few writers in Urdu have been, she was also an interviewer’s nightmare. Giggly, girlish and gossipy one minute, taciturn and evasive the next, charming and insightful one minute, imperious and opaque the next; she could leave you with a sand-slipping-through-your-fingers feeling. This was Qurratulain Hyder, the Jnanpith-award winning writer and grande dame of Urdu literature, admired by many, including this reviewer, and feared in equal measure for her easily-frayed patience.

And so, the intrepid Jameel Akhtar is to be congratulated for gleaning a marathon interview out of her and for having a free-wheeling conversation spread over several sittings on a wide range of subjects: books, music, painting, journalism, literary critics...culture in the broadest sense. Ably translated from the Urdu by Durdana Soomro, this book is a valuable tool to understanding Hyder and her craft, especially now that she has entered the syllabi and is being taught not merely in departments of gender studies but as part of the curricula on modern Indian writings. Quite literally, this book goes where no man has gone before! It takes us deep into the heart and mind of a famously temperamental, one might even say idiosyncratic, writer; taken together, as the sum of its parts, A Singular Voice gives us many valuable INSights into her craft as a writer and provides much-needed biographical details to fill the gaps in our understanding of Hyder.

For instance, her years as a ‘sari reporter’ working for the BBC in London, interviewing the ballet dancer Moira Shearer and reporting John Derry’s pioneering flight that broke the sound barrier and the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, reveal aspects of her life that haven’t been documented. Then there’s her stint as a film reviewer and a documentary film-maker for the ministry of information and broadcasting in Pakistan and later for the Films Division in India, her solo attempt at dialogue writing (for the film Ek Musafir Ek Haseena), her work on the documentary film Malwa, which fetched her the President’s silver medal in 1963, and so on.

Undaunted by responses such as “Enough, enough, enough!”, or “Oh, skip it!”, or “What a ridiculous question!”, Akhtar has performed a Herculean task. He remains mindful of the proviso Hyder sets before the interview, “But don’t ask any stupid or phony questions. I hate stupidity and phoniness! People talk such rot!” Apart from his subject’s famous moodiness, there’s also the issue of advancing age and habitual forgetfulness. “Every time I went, I had to introduce myself anew and had to restart our conversations from the beginning,” Akhtar writes. Despite her many digressions and a tendency of going off on tangents, Hyder’s recall of past events is near perfect: her idyllic and privileged childhood, her interest in painting, her growing up in a musically-inclined family, all this is revealed in splendid detail. However, those looking for masala will be deeply disappointed here, for she invariably clams up when it comes to what she deems ‘political’, ‘personal’, or ‘controversial’ questions. Having said that, her readers can finally hear Hyder in her own voice—restless, irritable, irascible even, but always herself—playing down some achievements and dwelling at great length on some others.

For all his patience and perseverance, Akhtar is unable to elicit any reasonable answer to two notoriously thorny issues: why Hyder chose to leave Pakistan and come back to India; and whether she had any differences with Khushwant Singh, causing her to leave the Illustrated Weekly. The book also falters in its lack of editorial inputs such as dates, details and descriptions of some of the randomly thrown-in names. With some footnotes and a little more rigour, A Singular Voice would have served the researcher and scholar better. What it does admirably is present the picture of a woman, unapologetically irreverent and individualistic, one who upon being asked why she doesn’t like abstract art, for instance, exclaims: “What do you mean why not? Obviously it doesn’t appeal to me. What would you say if someone asked you why you like carrot halwa?”