Hamlet’s soliloquising foetus, this novel’s prenatal protagonist and reliable narrator, cannot stand his uncle Claude, “who washes his private parts at the basin where my mother washes her face”. Worse, being in his mother Trudy’s belly means he is witness to their constant foreplay. “Here I am, in the front stalls, awkwardly seated upside down. This is a minimal production, bleakly modern, a two-hander.”

A bald pun in Shakespearean sexual stage directions follows. “With able thumbs, she hooks her panties clear. Enter Claude.” And later, “The briefest pause. Exit Claude.”

Clearly, there’s no epic snafu of the kind described in McEwan’s On Chesil Beach, forever parodied by the gifted Jim Crace as the couple that couldn’t “get over a crap shag on their wedding night”.

Hamlet grumbles, “Not everyone knows what it’s like to have your father’s rival’s penis inches from your nose. By this late stage, they should be refraining on my behalf. Courtesy, if not clinical judgement, demands it. I close my eyes, I grit my gums, I brace myself against the uterine walls. This turbulence would shake the wings off a Boeing.”

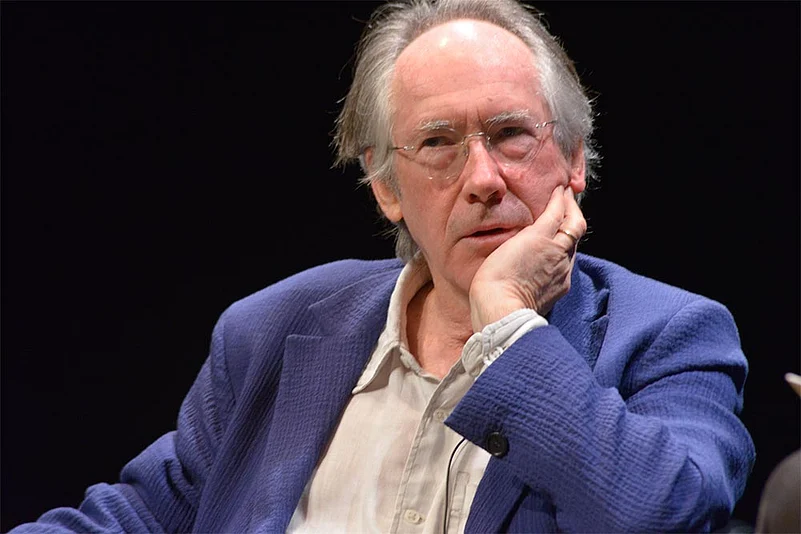

“I’m an Airbus man myself,” the author Ian McEwan quips about his own skill in the sheets at his book launch in Washington, DC. There is much laughter in the historic synagogue where everyone is gathered.

McEwan believes that “hesitation is a crucial element of creation. If people would rephrase writers’ block as hesitation, writers would feel better about it”. Both this baby Hamlet and the original are wordy and self-doubting. McEwan’s prenatal Hamlet is unable to act. The critic Harold Bloom has written, “In a running battle of wits.... I propose that a civil war goes on between Hamlet and his maker. Shakespeare cannot control this most temperamentally capricious and preternaturally intelligent of all his creations.”

So too is amniotic Hamlet, upset with his fickle mother for leaving his poet father John for John’s fratricidal property developer brother, a stupid man who always introduces himself as “Claude, as in Debussy”. “I refuse to say I hate her. But to abandon a poet, any poet, for Claude!” Hamlet is sensual when he describes his “gravidly ripe” mother’s “apple fresh arms and breasts and green regard I long for”. John is a poet without recognition, a publisher without money, a man without his wife’s love. Claude may soon take over John’s crumbly, stinky mansion in Elsinore, valued at seven million pounds. Worse is to come. Pregnant Trudy (Queen Gertrude) and Claude (King Claudius) thread torrid sex with chilling schemes that involve lacing fruit smoothie with anti-freeze. A helpless witness to their single-minded, often double-crossing, murder plot is Hamlet, now in his last trimester.

Will John be dismembered like that drunk ex-husband in the closet in McEwan’s The Innocent, or will it conclude with a car crash and childbirth, like McEwan’s Child In Time? Will Hamlet end up like the children who bury their mother in McEwan’s The Cement Garden?

Will the unborn Hamlet echo Christopher Columbus’s voyage by slipping down the birth canal like Carlos Fuentes’s Christopher Unborn? Will he finally get born like Tristram Shandy or the chatty baby Ruby Lennox in Kate Atkinson’s Behind The Scenes At The Museum? Or will he, like that other Booker winner, Bernice Reubens’s violinist baby in Spring Sonata, opt not to be born at all?

That, my dear readers, is the seven-million-pound question.

Whether Hamlet will be born may be anybody’s guess, but he is nobody’s fool. He has learnt everything from podcasts. Sometimes, he kicks his mother awake in the stomach so that she switches them on again. Trudy has a sweet tooth for Radio 4, so this precocious foetus basks in the auditory comfort of strangers all day. “I’ve heard it all. Maggot farming in Utah. Sexual etiquette among the Yonomami. The physics of tennis.” We can almost picture the baby narrator, Hamlet, in a three-piece, smoking a cigar. He listens to a radio drama on the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, and to Babies Behind Bars, and asks why it is “enlightened” to put children of criminals in prisons.

McEwan’s 17th novel, Nutshell, is an updated, mildly comic prequel to the tragedy of Hamlet. Unlike Iris Murdoch’s Black Prince or David Foster Wallace’s teeming Infinite Jest, which used Hamlet only as a jumping off point for other literary explorations, Nutshell sticks to Hamlet’s father’s murder, and is told from the point of view of Hamlet. The situation certainly calls for wit (he wants to pull the umbilical cord for more drinks) or suspense (he tries to kill himself by tangling himself in that cord).

Laurence Olivier as Hamlet in the 1948 film version

There are lengthy diversions. Hamlet worries about things like climate change and terrorism. He mocks identity politics (McEwan is on the wrong side of history here, like when he supported the Iraq War). Hamlet is introduced to John’s ‘friend’ Elodie, a young owl poet who ‘quacks’ like a duck. Does he have a secret girlfriend? When John asks Trudy to move out with Claude, things get really sinister.

The problem with Trudy is that she an alcoholic, consuming five glasses in one go, cutting her feet on glass, almost rolling down the stairs. But baby Hamlet is an urbane oenophile. “You may never have, or you will have forgotten, a good burgundy (her favourite) or a good Sancerre (also a favourite) decanted through a healthy placenta.” In a macabre scene, a bottle of poison stands next to the empty wine bottle, as they all drink. Hamlet could well be Hannibal Lecter, slicing and sauteing his dinner guest’s brain and serving it with fava beans and Chianti. He is only guilty by association, as his survival is tied with his mother’s...“unless, unless, unless...a bleating iamb of hope.” Unless he can find a way out.

Theo Tait said in his review of McEwan’s The Children Act, “For some years, I have nursed a modest hope concerning Ian McEwan: that one day he should write a novel without a catastrophic turning point, or a shattering final twist. That, for once, no one should be involved in a freak ballooning accident, or be brained by a glass table, or be wrongly convicted of a country-house rape; that no one should experience a marriage-ending bout of premature ejaculation, or have their child stolen in a supermarket, or suffer a terrifying home invasion at the hands of a thug with an easily diagnosed neurological condition. Wouldn’t it be good to see him do without his habitual narrative crutches: the constant undercurrent of menace; the crafty, miserly paying out of crucial plot information; the old 180-degree switcheroo in the final pages? This is not to denigrate any of the above. Many of those sequences are among the most celebrated passages of recent English fiction.” Perhaps Theo Tait’s day has come. The prose is as polished as ever, but very little of the plotting above is on display here. There’s a lot of philosophising, but only a bit of claustrophobic action—all indoors for Trudy and in utero for Hamlet. McEwan’s sixth Booker nomination may have been his last.