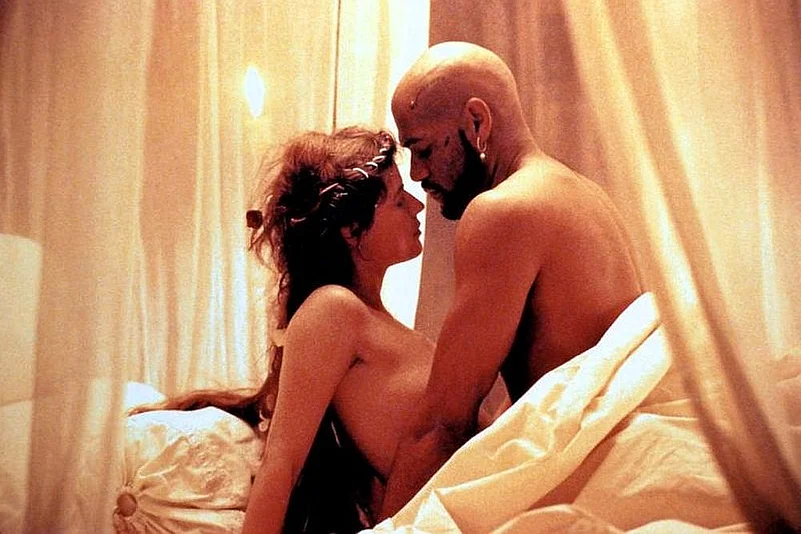

Ah Othello. That old what-not-to-do manual on jealousy, gossip and nasty tricks. Don't steal hankies, don't confide too much in your right-hand man. Don't choke your new wife to death…the list goes on. Whether it's Kareena Kapoor catching an injured Ajay Devgn at the door or Laurence Fishburne getting steamy with Irene Jacob, whether you are an ardent Shakesnob or simply a curious movie-goer, it is one story where the fairytale violence of Romeo and Juliet turns several shades darker and it gets a bit harder to make pop songs out of the massacre. But that's not the only reason why Othello is a more preferable play (at least to me). Each time I revisit it, I am also blown away by the sheer intensity and scale of the bard's exploration of that wonderful, timeless plot fodder: toxic romance.

Consider this: "T'is not a year or two shows us a man :/They are all but stomachs, and we all but food/They eat us hungerly, and when they are full,/They belch us." Othello III.iv. 100-104.

So go Emilia's withering lines to explain men to a bewildered Desdemona. And she is not alone. This short speech has a fraternal twin earlier in the play by Iago—

I know our country disposition well :/In Venice they do let God see the pranks/ They dare not show their husbands; their best conscience/Is not to leave't undone but keep't unsure. Othello III.iii. 201-4

The thing about both speeches is that the opposite sex is generalized to hell. And in the process, an individual man and woman are explained through a potent set of gender expectations that become self-fulfilling prophecies. In Othello's case, at least, it is the knowledge of women sourced from Iago that leads to the confirmation of Emilia's already-formed expectation about his behaviour. Shakespeare treats sex like an unexploded minefield, and his Emilia and Iago are the sarcastic tour guides to it. Together they create an atmosphere of intrigue where romance between Othello and Desdemona quickly break down into short one-line retorts. Retorts inherited from a couple married for longer. Time to call Shakespeare a cynic about love? May be. After all, Emilia and Iago are certainly not in love. Hence Emilia's sexual weariness ('I might do't as well i' th' dark') and Iago's beastly treatment, ending in murder. But then, marriages are an area where Shakespeare is repeatedly skeptical. Look at the fate of Hamlet (the elder) and Gertrude; Oberon and Titania or even Kate and her Petruchio. The only remotely successful couple are the Macbeths, that's only because regicide is better than marriage counselling.

But both Othello and Desdemona protest that they are the exceptions. Othello's first response to Iago's insinuation is a vehement defense for the right of women to enjoy themselves, love company, speak freely, sing and even dance and still possess the right to virtue. Similarly, Desdemona responds to Emilia's utilitarian view of fidelity with horror — 'Beshrew me, if I would do such a wrong/ For the whole world'. But, of course, there would be no tragic momentum without the collision of two discrete yet parallel philosophies about sexual relations in Othello. The collision is planned and carried out by Iago, a man navigating the complex world of gender identity with 'motiveless malignity' never more apparent than in his absolute hatred towards sexual love.

And so this Shakesvillain deploys a language that deliberately forces a perverse imagination of the body upon his listeners. In the opening scene with Brabantio, he visualises Desdemona's elopement as 'an old black ram…tupping your white ewe' and later as 'your daughter covered with a Barbary horse' and finally 'the beast with two backs'. The images begins by making Desdemona into an animal in a racially charged way ('white') and ends with sex as a strange conjoined apparition calculated to nauseate.

As the play progresses, Desdemona and Othello become isolated from everyone except the other couple, who assume the power to interpret the new spouses to each other. Once in control of Desdemona, Emilia corrupts the story that Othello had once told when he and Desdemona fell in love — 'It was my hint to speak — such was my process —/And of the Cannibals that each other eat/The Anthropophagi'. Emilia makes the impressionable Desdemona see her own husband within the story, making him a man 'that is all but stomachs', a cannibal who inhabits the description rather than her savvy husband who can narrate it.

(On a lighter note, the play is pretty obsessed with eating anyway. Othello too describes Desdemona's growing attention as 'a greedy ear' and later says 'Devour up my discourse'.)

But back to the toxic romance. As Othello and Desdemona become willing listeners to Iago and Emilia, they lose their individuality, for their adviser-insinuators can only address gender as a one unbroken category. Iago's narrative of the opposite gender leaves no scope for Desdemona to clarify, confirm or deny the accusations of her husband without implicating herself as an outsider — not of 'our country disposition' and therefore even further away from believability. Shakespeare scholar Carol Chillington Rutter summarises the predicament of both Emilia and Desdemona perfectly when she lays out the scheme 'silence equals chastity; all women talk; [thus] all women are whores'. Iago demonstrates his hostility to a woman speaking in the first scene of the second act when he responds to Desdemona's observation about Emilia — 'Alas! She has no speech' with a curt 'I'faith too much'. As it transpires in the next line, he even resents her thoughts.

In Iago's discourse of women then, silence of speech and thought is of paramount importance. Since speech compromises pure objecthood and offers a challenge to Iago's story, it must be suspected, accused and held in contempt. The underlying tenet gives Iago the logic to preemptively attribute infidelity to Desdemona on the basis of her defiance of her father. The defiance is interpreted as deception even though she never lies to Brabantio within the play.

Now to the eternal trope of icky love: baby-talk. Imogen Stubb's Desdemona in the Royal Shakespeare Company Richard Price production speaks in a child-like soft lilt. She is constantly towered over by the larger Othello and taller Iago and finally, mothered quietly by an older Emilia in the hair-brushing scene (IV.iii). Brabantio describes her in the play as a 'maiden never bold;/Of spirit so still and quiet that her motion/ Blush'd at herself'. In her death she is invisible too, 'covered' as Iago had once said, by the strangling bulk of Othello. Meanwhile Omkara has Desdemona (Dolly) die on the night of her delayed wedding ceremony, on a swing covered with flowers, more a resting child-bride than an adult woman.

And speaking of the climax, Desdemona's death destroys the stability of the couplings Othello-Desdemona and Iago-Emilia. Othello, Iago and Emilia all find themselves unhinged from the axes of trust that were taken for granted before. Emilia can no longer trust Iago or Othello; Othello can no longer trust 'honest' Iago; Iago cannot depend on the obedience of Emilia. In this vacuum of intimacy Emilia replaces Othello as the closest person and bedfellow to Desdemona — 'Ay, ay! O, lay me by my mistress' side' and it is Iago who is robbed of speech.

The power of storytelling is transferred on to Lodowick who leaves to 'this heavy act with heavy heart relate'. One way to explain Iago's 'motiveless malignity' is the theory that he himself secretly lusts after Desdemona. If so, then Emilia's death is a double-revenge upon him, both exposing the man as the criminal as well as demanding a very public reckoning about the lust. But it is a long shot, and there is very little erotic force in the gaze that Iago turns with equal greedy distaste upon Desdemona, Othello and Cassio. It is more interesting to instead read Othello as a play where the gender relations of both Tudor England as well as our own fraught contemporary time crystallize into the tragic deaths of two women as they attempt to flee and protest against the narrative that one violent and deranged man fashions for them.

Obviously, part of the charm of reading Shakespeare is that you can never pin him down to a morale. But one thing is for sure — this was not a writer who had much truck with Happily Ever After. And certainly not much faith in the possibilities of a squishy, cute romance.