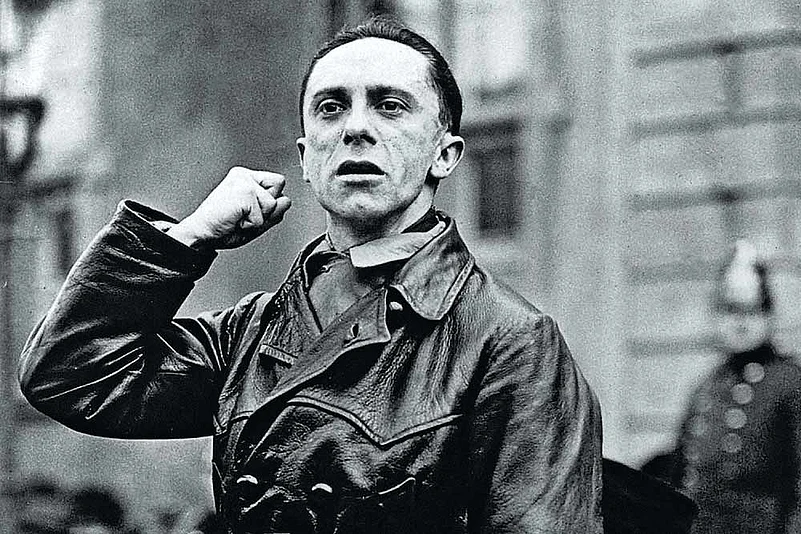

At a time when opinion makers and common people living in the world’s oldest and largest democracies—United States and India—are struggling to differentiate between propaganda and factual information, this latest book by a philosophy scholar from Yale University, Jason Stanley, offers an interesting insight into the subject. Setting the tone in the very beginning for what is in store, the book begins with a quote of the Reich minister of propaganda, Josef Goebbels, during the 12 dreaded years of Hitler’s rule. Goebbels is quoted as having said: “This will always remain one of the best jokes of democracy, that it gave its deadly enemies the means by which it was destroyed.”

Propaganda ministries may not exist in any of the democracies in the world today (though Stanley points out a ministry by this name does exist even today in Cuba). Dwelling at length on the genesis and evolution of propaganda across the world to its effectiveness today, it makes readers aware that propaganda tools which were originally associated with totalitarian regimes, are now fast spreading to democracies and do pose a threat to them as well. It offers a new and more than traditional definition of propaganda, which so far has been termed by scholars as biased and misleading information to promote a particular political cause.

Stanley differs and defines it as: “Propaganda is characteristically part of the mechanism by which people become deceived about how best to realise their goals, and hence deceived from seeing what is in their own best interests.” He further states this is achieved by various time-tested means, by appealing to the emotions so that rational debate is completely sidelined. Propaganda is considered successful when it appeals to the feelings of people rather than to their reasoning ability and relies on stereotyped formula, which are repeated over and over, to firmly drill these into the minds of people. For any propaganda to be effective it has to use simple formulations, like love or hate and right or wrong, to demolish the enemy while making intentionally biased and one-sided arguments.

Stanley’s research could not have come at a better time, given the grave threats posed by fake news and unregulated content available all across social media platforms, which can fuel unrest of unimaginable scale, leaving no room for reality or sanity to be disseminated among the masses. There are numerous examples of how US governments have successfully propagated lies in 21st century to further their geopolitical agendas. One of the most glaring examples was linking the then Iraq president Saddam Hussein to the 9/11 attacks by the Bush administration, which successfully finished any chances of a rational debate.

Images of Colin Powell making a powerful presentation before the UN Security Council about Saddam possessing chemical weapons are still fresh in the minds of journalists who covered the 2003 Iraq war. The same propaganda was passed off as credible information by Tony Blair to ally with Bush for attacking Iraq. A decade later, both the US and the UK have virtually admitted that there was no credible evidence about Saddam either having been a part of 9/11 attacks or having possessed chemical weapons. Whether those who propagated lies will ever face any consequences in this unipolar world is anybody’s guess, but one of the reasons for the easy credulity of misinformation could be the voracious appetite of the public for sensationalism, scandals and entertainment, coupled with widespread media obsession for ratings.

This book does not directly refer to the kind of campaign run by Donald Trump for his presidency, but does refer to Obama’s challenger in 2012, Mitt Romney, having tried to present a distorted views of welfare schemes of the Obama administration during the elections. This is why propaganda, which provides a simple and convenient narrative for processing events, thrives in a polarised environment in which truth is regarded as relativistic and facts are treated as fungible. And it’s how reality-distorting propaganda undermines the reasoned deliberation that is so essential to democracy.

The book has a blurb by none other than one of the leading academics of our times, Noam Chomsky, where he says How Propaganda Works is a significant contribution that should revitalise political philosophy at a time when democracy is fraught with political campaigns, lobbyists, conservative and liberal media. Interestingly, though, Stanley does not completely agree with Chomsky’s analysis of propaganda in the book.

(The writer is currently media advisor to the Delhi chief minister)