It was former US State Department officer Joseph V. Montville who had coined the word ‘Track-II’ while writing in Foreign Policy (Winter-1981-82) on conflict resolution negotiations. He was defining attempts by non-official channels to find common ground that official negotiators (Track-I) could not. But Montville did not invent the process. President Dwight Eisenhower had used it through Norman Cousins, editor of The Saturday Review, to break a stalemate in negotiations with Soviet Union during the Gary Powers U-2 Spy plane incident (1960-62). Cousins had set up the ‘Dartmouth Conference’ in 1960, assembling American and Soviet intellectuals for informal dialogue.

READ ALSO: Espionage Diary

But Montville did not consider ‘Track-II’ as a substitute for ‘Track-I’. The aim of both tracks is problem solving and not mere dialogue. Montville’s Track-II only provided a ‘bridge’ to facilitate decisions through Track-I. He envisaged situations when “people who have the trust of their groups” could “influence the top leadership” of conflicting nations.

The book under review is a record of Track-II ‘Intel Dialogue’ (intelligence dialogue) during 2016-2017 between former ISI Chief Gen. Asad Durrani (1990-92) and former RAW chief A.S. Dulat (1999-2000) in Istanbul, Bangkok and Kathmandu, moderated and recorded by senior journalist Aditya Sinha. It covers practically all facets of India-Pakistan issues, personal interpretations of both on bilateral and multi-lateral developments, including intelligence and their recommendations for the future.

However, neither Dulat nor Durrani could claim that they had the ‘trust’ of their governments. This is not due to their fault but due to changed circumstances in their countries. Durrani had a reputation as a non-political intelligence chief who risked many bumps in his career, according to Hein G.Kiessling of the Ludwig Maximilian University, author of a history of the ISI (Faith, Unity Discipline—The ISI of Pakistan, 2016). The book is considered to be a semi-official account, as ISI had supplied official versions to the author.

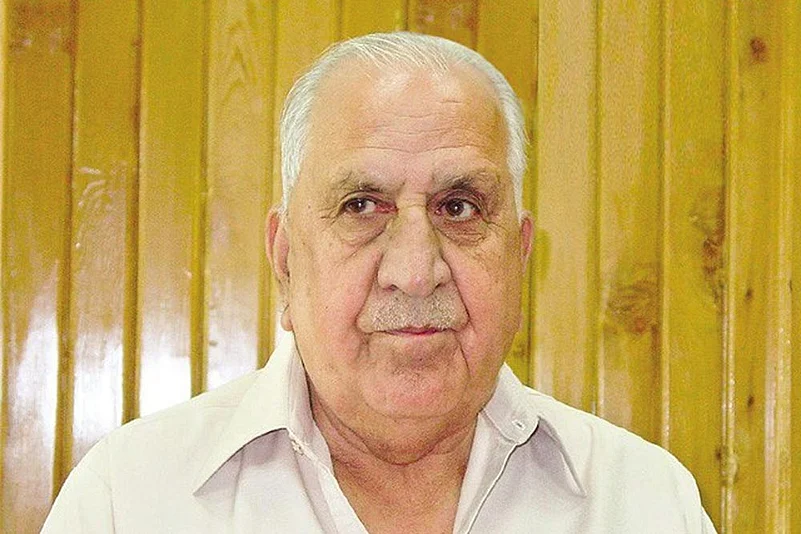

Naseerullah Babar, a creator of the Taliban along with Col Imam

In 1988, Zia was so annoyed with Durrani for giving a lecture on democracy at the National Defence College that he blocked his promotion. In 1990, prime minister Nawaz Sharif reluctantly appointed him ISI chief, but removed him in March 1992. After the publication of the book under review, he has been called to order by his GHQ at the suggestion of Nawaz Sharif for violating the military code of conduct in airing views deemed against the official stand, especially the Abbottabad operation involving Osama bin Laden.

Dulat, who worked for long years on the Kashmir desk in the Intelligence Bureau, was a very successful RAW chief. In 2000, PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee chose him as adviser for the crucial Kashmir dialogue. Dulat reveals that it was his idea to suggest to the newly elected prime minister, Narendra Modi, to invite Nawaz Sharif for his swearing-in ceremony in 2014, as his contacts in Srinagar had suggested that “he was keen to come”. He confirmed this through Durrani and passed it on to the new ‘bigwigs’.

A typical Track-II should include the dialogue partners’ frank assessment of intentions, capability and vulnerability of both countries to allow people to judge, even in posterity, whether a real confrontation between them was in the offing. It is good that Durrani had revealed that there was no possibility of an India-Pakistan war when the ‘Gates Mission’ in May 1990 had triggered fears of a nuclear confrontation. This was in the wake of a sudden spurt in the Kashmir insurgency, Pakistan’s Zarb-e-Momin exercises and India’s retaliatory action.

But Durrani is not as revealing on other issues, which had deeply disturbed India even when he was holding office. Kiessling wrote that Durrani headed the ISI (August 1990 to March 1992) during “a period when Kashmir, Afghanistan and internal affairs were the ISI’s main concerns”. Yet he does not reveal how and why turbulence had suddenly burst open in Kashmir in December 1989, after Rubaiya Sayeed’s abduction just prior to his taking over as ISI chief.

Even the late Hamid Gul had frankly told the then RAW chief, A.K. Verma, in the 1980s, during their initial secret Track-I meeting in Amman, that Pakistan was backing Sikh terrorism as it was afraid of India. He said that they would stop supporting terrorism if India made enough movements towards confidence building measures (CBMs). On his part, he did make certain movements which had benefited India. That type of frankness was absent in Durrani. On May 5, 2011, he was quoted by Reuters as saying, “Terrorism is a technique of war, and therefore an instrument of policy”. He had made the statement when the Guantanamo interrogation documents, connecting the ISI with terrorism, were leaked.

Although he denied ISI’s K-2 operation (Kashmir-Khalistan) as beyond Pakistan’s capability, he tells Dulat that “this is not the right time to start playing the Sikh card, the Kashmir card, the ULFA card”, adding that the “idea was to keep it on a leash” as neither ‘side’ wanted a war. He is also ambivalent on official Pakistani involvement in 26/11.

Durrani claims that no ISI man had ‘defected’, like from RAW. Quite true. The last big defector, Rabinder Singh, could flee due to RAW’s own intransigence of not handing over the investigation to the IB. But then, no other official espionage agency has been in the swim with terrorists as the ISI. The classic example is ISI stalwart Col. Imam (Sultan Amir Tarar) who, along with Naseerullah Babar, had created the Taliban in 1994 with the help of then DGMO Pervez Musharraf, by giving them the entire Pakistani arms cache in Spin Boldak on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. RAW could monitor this development, taking advantage of an open conversation between President Farook Leghari and Babar. The same Col. Imam was brutally killed in February 2011 by Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Dulat should have asked Durrani how the ISI keeps the integrity of its cadre when faced with such dangerous elements.

Yet, the dialogue should be very interesting for Indian readers as we are yet to develop a culture of studying intelligence as a tool for formulating policy. Consequently, we have produced only motivated or vainglorious intelligence literature, fit for Bollywood thrillers. At the same time, their remarks on current decision makers or ‘hawkish’ career foreign service officials (Part IV: Kabuki) might excite the media, but do not help either country in finding solutions.

A comparison with another book, jointly written by CIA-KGB operators, and moderated by a US journalist during the US-Russia bonhomie during the Yeltsin presidency (1991-1999), may be relevant. In 1997, Yale University managed to produce a mammoth book, Battleground Berlin-CIA Vs. KGB in the Cold War, jointly written by David Murphy (CIA) and Gen. Kondrashev (KGB), who were in charge of rival Berlin stations. Like Aditya Sinha, this dialogue was moderated and recorded by American journalist George Bailey.

The book reproduced 250 secret file extracts and 87 photocopies of original documents. For the first time, it was possible to compare both services together, how they worked and fought with each other. It divulged that the Soviet services had access to the “highest reaches of the American, British and French governments”. It revealed how Gen. Donovan, father of American foreign intelligence, was deceived by NKGB in 1943 during the Second World War when he visited Moscow for proposing intelligence cooperation. Moscow happily agreed. What Donovan did not know was that his personal staff officer, Duncan Chaplin Lee, was already on the payroll of the NKGB!

Finally, the take-away: The Chronicles refer to Dulat and Durrani’s common paper on ‘Intelligence Cooperation’ published in The Hindu and Dawn simultaneously (July 14, 2011). It recommends that both agencies should serve as ‘back-channel’ for their governments to pave way for political dialogue. In Chapter 31, they have recommended the institutionalisation of ISI-RAW representatives’ meetings. Former Union home minister P. Chidambaram had tried this out in 2010.

This would be similar to the secret, deniable ‘Gavrilov channel’, which CIA and KGB had established in the 1980s to set limits “on certain extremes of behaviour by agreeing on unwritten rules of the game”.

(The writer is a former special secretary, Cabinet Secretariat)