In September 2007, the NIS (South Korean Intelligence) earned international acclaim for getting 21 of their Christian missionary hostages released from the Afghan Taliban who had abducted them and killed two of them. Details of this six-week covert operation are still fuzzy. Around the same period, India could do nothing to rescue BRO’s Maniappan and Telecommunication’s Suryanarayana, who were abducted and killed by the Taliban.

King of Spies by Blaine Harden, former Washington Post correspondent, is an incredible story about how the foundations of this remarkably effective but controversial intelligence organisation were laid under the watch of a 23-year-old US ‘Counter Intelligence Corps’ (CIC) NCO during the American occupation from 1945. It is amazing how this school dropout from a broken family in Hackensack (New Jersey) could head a large intelligence group in South Korea, even rivalling CIA and how he became the closest advisor to President Syngman Rhee from 1946 to 1957. Yet it is also a tragic narrative of his abandonment by his country, whose security interests he thought he had protected and his lonely death in an Alabama psychiatric hospital in 1992.

Private Donald Nichols joined the US Army in 1940, became a carburettor repairman in Hawaii, then in Karachi and was recruited by the Army’s CIC. In 1946, he was sent to Seoul, where Harvard-educated Syngman Rhee was the president, despite objections from US State Department and CIA (“vain, delusional and dangerous”). Nichols cultivated Rhee from August 1946 through Kim ‘Snake’ Chang-ryong, a former Japanese military officer notorious for killing thousands of South Korean Communist suspects. Nichols and Rhee became so close that the latter started calling him his ‘son’.

Nichols worked closely with the S. Korean police, who were trained by the Japanese in various torture methods. Rhee executed a large number of opponents through the police, watched by Nichols, like the one on April 14, 1950, when 39 “confessed Communists” were killed. His seniors did not report these massacres to Washington DC. Nichols used this access to cultivate North Korean defectors and also visited North Korea clandestinely.

American military leaders, including Gen. MacArthur, did not think it odd that a sergeant with elementary school education should be the “private confidant to a head of State”. Nor did they put Nichols under “meaningful supervision” to prevent America being stigmatised by Rhee’s human rights violations. Harden says that 30,000 to 1,00,000 South Koreans were killed under Rhee before the Korean War started on June 25, 1950.

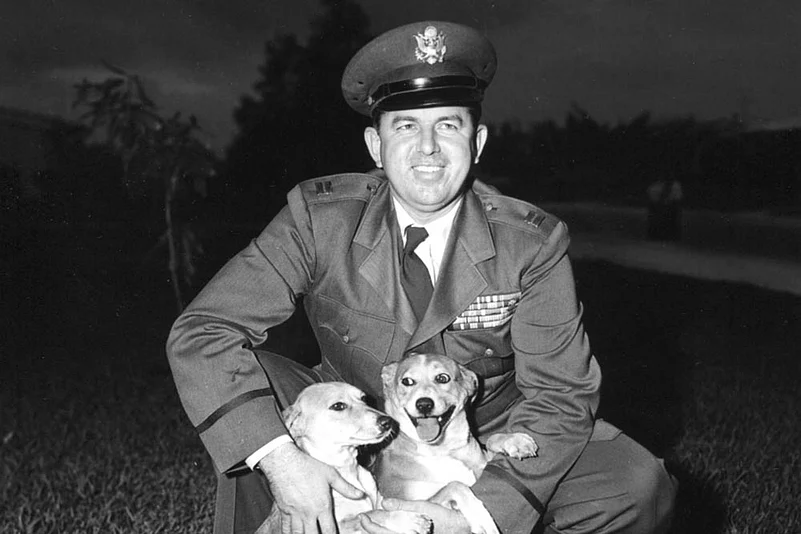

The pinnacle of Nichols’s career was during the 1950 North Korean invasion. The US military had no idea of signals intelligence through code breaking when the North Korean army overran Seoul on June 30, pushing them to Pusan. Nichols saved the situation by enlisting a North Korean defector, Cho Yong II, an expert in code breaking. From Taegu, he could intercept more than 2,000 communications on North Korean deployment for successful bombing by the US Fifth Air Force, which halted and beat back the invaders. Nichols’s reputation soared. He was awarded the Silver Star, America’s third highest military honour. Rhee gave him South Korea’s second highest military honour. By 1952, he came to command a huge intelligence unit named ‘6004th Air Intelligence Squadron’, also called ‘Nick’, with 50 detachments, thus rivalling army intelligence and the CIA.

Along with his reputation came reports of his excesses. He killed his own spies if they betrayed him, some by pushing them out of helicopters. The US wanted to get rid of Rhee, who had ‘judicially’ eliminated his political rival, Cho Bang-am, in 1958 on a spurious charge of conspiring to assassinate him. Nichols also could not escape the blame. His downfall started in 1957, four years before Rhee was forced out of office. He was recalled to the US, admitted in a psychiatric hospital, given electric shocks and forced to retire. Between 1957 and 1992 he faced prosecutions for abnormal behaviour, including paedophile charges.

Ironically, President Truman, who had spurned military claims by the leadership of the newly created CIA in 1947 as the successor to Second World War OSS, could not enforce that principle on overseas territories. The book is also a lesson to all intelligence agencies, including ours, that violence used as intelligence tool or unsupervised intelligence collection by armed forces without civilian checks and balances does not survive as good policy.

(The writer is a former special secretary, cabinet secretariat)