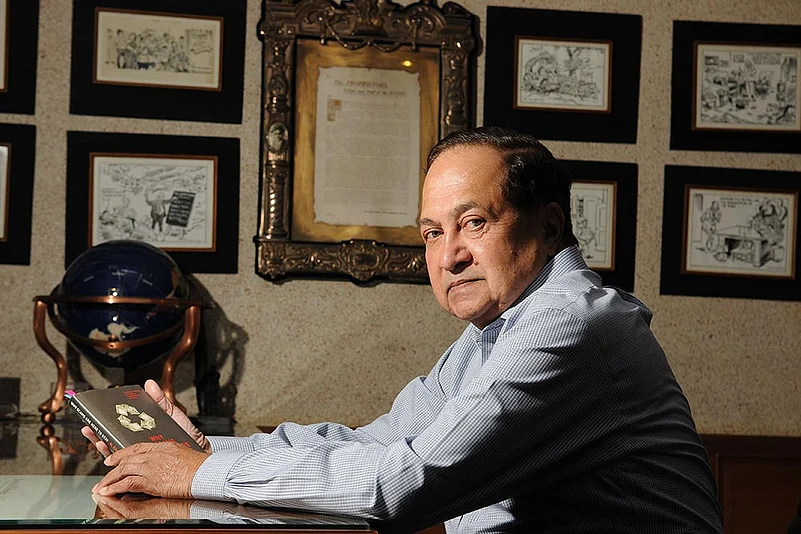

N. Ram has been the face of The Hindu as its editor-in-chief and now as chairman of the group. As deputy editor he spearheaded the newspaper’s investigation into the Bofors scandal, a watershed moment in investigative journalism in India. That pole position offered him the vantage point to unpeel the layers behind India’s political corruption. And the result is his book Why Scams Are Here To Stay—Understanding Political Corruption in India. In a decade that has seen scams scurrying past us, the book is an attempt to “understand what kind of animal corruption is in India”. He spoke to G.C. Shekhar about the book and if India has a way out of corruption.

We know political corruption exists in India. At what scale? Can it be tackled at all?

Corruption is intractable unless you effect radical changes and completely overhaul the present system of political economy. You cannot get rid of it. At the same time you cannot wait for a revolution to happen. It’s a challenge that has to be tackled here and now. You have a situation where the entire system is corrupted. Where policies are hijacked, not just individuals, bureaucrats or politicians. An example would be the 2G scandal. Bofors in my view is the defining grand corruption scandal in India, not because of the size of the kickbacks—Rs 64 crores in alleged bribes. But because all policies were tweaked. The French gun was chosen originally but got bypassed. The government’s cover up, crisis management...defence acquisitions came to a halt. We paid a heavy price for it. They tried to blame us (The Hindu) for it, but you have to blame the system.

Was there pressure to go slow, or not to publish by the Rajiv Gandhi government? Was the anti-defamation law a response to the Bofors expose?

Later on, at one point there was. But it was too late, as most of it had come out. The media fought off the 1988 anti-defamation bill successfully. But now you don’t see the same solidarity, spirit and mobilisation.

On Bofors you also faced internal pressure. You and your editor Mr Kasturi had differences on what to publish. You even held a press meet in Delhi and alleged that you were being curbed and The Hindu employees struck work for a day, urging the two of you to sink your differences. How did you sort that out?

He treated it as a difference of opinion. He had others to support him. He stepped down as Editor after that episode for whatever reason. But I maintained excellent relations with him. He was my uncle. Yes, for a while there was bitterness. But it healed very quickly. If you don’t question people’s motives it is easier to get over.

Compared to the days of the Bofors scandal, have we not seen courts convicting more politicians and sending them to jail—Chautala, Laloo Prasad Yadav, Chhagan Bhujbal, Jayalalitha and the likes?

Partly it’s sheer increase in corruption. Some of them get caught in court. There is also the impact of public opinion. The immunity from investigation and prosecution top politicians got has been diluted. But I do not agree with EC that one shouldn’t be allowed to contest elections when chargesheets are filed. You can foist cases and courts cannot be relied upon.

In the context of the Supreme Court verdict in the wealth case against Jayalalitha, you have observed that “the country was spared the prospect of another notoriously corrupt politician-in-the-making V.K. Sasikala being sworn in as CM of a major state”. And yet you were the first senior journalist to call on her (on Dec 13) after Jayalalitha’s death.

There is no problem with that meeting. Journalists would give a lot to meet Sasikala. I got a message—‘she would like to meet you and chat’. I readily agreed. I asked her every question I could, including why she was thrown out, whether she wanted any position in the party. She kept quiet. She described Jayalalitha as a child inside the house, but a chief minister with full authority once she stepped out. Journalists should have no problems meeting anyone. We have met people like Prabhakaran—killers. There was no cosy talk or advice (with Sasikala).

Your book, in passing, mentions the ‘unsavoury nexus’ between politicians, corporates and journalists based on the leaked Radia tapes. Do you think journalists are far more involved in the system than they should be?

Than they let out, yes. But it’s not a good thing. Even if you are involved you should keep your personal relations separate from your writing. Walter Lippman called it cronyism. He knew all the presidents, still you should keep a distance, he would say. I had experiences with people like Rajiv Gandhi, Jayawardena and even LTTE. It is not so easy. When you know someone very well you tend to filter out more critical opinions. I have known Mr Karunanidhi for a very long time. But he was not always very pleased with what we wrote.

Why then did The Hindu hire someone referred to in the Radia tapes?

When Siddharth (Varadarajan) left, he (M.K. Venu) went. I won’t be harsh on him. I made that comment on Barkha Dutt and she didn’t talk to me for a while. Venu’s involvement doesn’t show any corruption. But we don’t know the circumstances. On Radia tapes either they do it or pretend to do it— ‘we will get you this portfolio and so on’. Nearly ten years ago, Cho Ramaswamy said, ‘let us go meet Rajnikanth. You should help me persuade him to come to politics, as he is a desirable type’. So we went. And the same response that comes today (from Rajni) came then—that when the inner call comes I will come. I didn’t try to persuade him. I watch. It’s a thin line. You respect what the person says and you learn from it. Radia tapes showed things beyond that. They looked very compromised. Siddharth had brought Venu in and he left when Siddharth left. I had differences with him. I am on very good terms with Siddharth now. He is doing a good job at The Wire. It didn’t work out here.

The Hindu, mainly P. Sainath, had written about paid news in Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. That is also a form of corruption. How do we fight that?

Prabash Joshi also wrote about it, yes, but mostly Sainath. During election time everyone, including the Election Commission, is conscious of paid news. Also the press council, working journalists’ organisations. But paid news round the year, that is the real thing. When there is a scandal...we all report it. What about the endemic thing? Paid news takes place all the time. Not with every publication or journalist, but a significant section. Corporates do paid sections. Politicians do it round the year. But during election time it is crude. It’s like a package—the same thing comes in different papers.

Nothing came out of it. But I can’t guarantee that not a single journalist from our group is not corrupt or not susceptible to this sort of thing. Favours may have been exchanged. In this particular case there was no follow up. We rebutted it. Nothing was brought to our attention.

A whistleblower who wrote about it.

Yes, I was aware of it. There was no evidence. We contested it. On occasion, we have asked people to leave who were not straight. No organisation is immune to such things. We have a whistleblowing policy with The Hindu applicable to everybody. In one case it actually worked. The union was the whistleblower.

Are people becoming inured to corruption or do you think a revolution against political corruption is waiting to happen?

There will be no one revolution. There is an ebb and flow. There are times when people get agitated, mass mobilisation becomes a reality. We saw that with Jayaprakash Narayan’s movement in the ’70s before the Emergency. And then the Anna Hazare movement. Arvind Kejriwal was smart in moving away from that and form a political party. Such moral campaigns against corruption are not useless. They bring about public awareness, some kind of change. But the high objectives they set themselves are something that can never be realised.