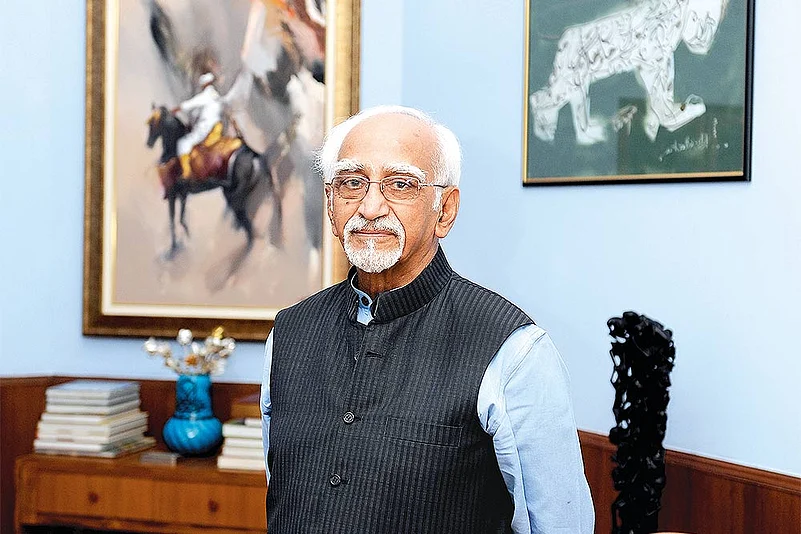

The former vice president, Hamid Ansari, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi represent the two ideas of India that are today in existential competition, the outcome of which will shape the national polity for decades to come.

As Ansari prepared to relinquish office, he voiced the feelings of several million Indian citizens when he spoke of the “enhanced apprehension of insecurity” among the country’s minorities and of “a sense of unease creeping in” among Muslims. The prime minister dismissively explained Ansari’s views as resulting from his long diplomatic career in Muslim countries and his subsequent association with minority issues, referring to his tenure in the Minorities Commission.

This book compiles some of Ansari’s last public pronouncements as vice-president, at the heart of which is his understanding of India’s history and culture, whose values are enshrined in the Constitution. These are: promotion of harmony, preservation of India’s composite culture and development of a scientific temper.

These values are under assault at present from Hindutva, the ideology and mindset that rejects the pluralistic nationalism of the freedom struggle and the Constitution and, instead, offers the idea of ‘cultural nationalism’ anchored in the exclusivist framework of Hindu race, religion and culture. Hindutva sees India’s eclectic heritage not as enriching the national ethos, but as alien contamination and demeaning defeat.

Ansari challenges the shallow historicity and calculated manipulation of the political reality of Hindutva votaries with a wide garnering of facts and opinion, presented with erudition and uniform courtesy.

Ansari takes issue with the Hindutva insistence on an “imagined uniformity” that finds no support in India’s past or the reality of its present. The idea of ‘Indianness’, Ansari asserts, is based on “the widest possible circle of inclusiveness” and sees the Hindutva-based intolerance of diversity and dissent as reflecting a “fragile national ego”. The title itself suggests the trepidation of even exalted personalities in voicing contrarian views in the prevailing political climate.

Ansari includes in his discussion concerns relating to social and economic inequality and status of women. He notes the halting, even reluctant, efforts of the state to dismantle patriarchy and demands a robust commitment to “substantive equality” for women in the political, social and economic order.

He expresses deep concerns about burgeoning global and national inequality: the richest in India own 60 per cent of the national wealth, while the bottom half collectively own 2 per cent. He notes that rising inequality has engendered authoritarian rulers, with the latter pursuing an agenda often defined by sectarianism, xenophobia and hyper-nationalism.

Ansari discusses the steady decay of national institutions. Thus, Parliament’s composition hardly reflects the national gender and social diversity, and, working for just 57 days in 2017, it has become largely non-functional. The executive too is increasingly ineffective as the divide between political compulsion and professional integrity in the civil and police services has blurred.

Judicial activism is now the norm. But, this has had mixed results, given the plethora of judicial pronouncements on a wide variety of national and local issues, even as the judiciary itself is crippled by high cost of access, severe delays, and inadequate mechanisms for ensuring its transparency and accountability and addressing allegations of corruption.

Ansari notes that electoral democracy is no longer adequately “substantive, inclusive and participatory”, even as fundamental national values of pluralism, secularism, egalitarianism are being challenged by an illiberal, exclusivist and intolerant national discourse.

In the face of these challenges, Ansari goes back to Ambedkar who, in 1949, had warned about the need to safeguard constitutional values. He had then INSisted on the need to always use constitutional methods to obtain national objectives and to be wary of hero-figures whose untrammelled power would subvert democratic institutions.

Most importantly, Ambedkar had urged us to recognise that political democracy would have little value unless it was founded on ‘social democracy’, which would give justice, equality and opportunity to the disadvantaged and the vulnerable.

Today, central to the Hindutva discourse is the ‘othering’ of Muslims and other minorities, as is reflected in Modi’s response to Ansari’s observations. Here, Ansari’s riposte is apt: in the Indian political order, “the ‘other’ is to be none other than the ‘self’.” This encounter of our national stalwarts encapsulates the ongoing debate on the legacy and destiny of India.

(The author is a former diplomat.)