I can still remember the afternoon, on my 15th birthday, when I opened up The Virgin and the Gypsy, D.H. Lawrence’s novella, in my tiny cell in boarding school, and whole worlds of possibility opened out that I had never guessed existed. The language was on fire and sang of liberation. The author was so wide-awake he could tell me how the crocuses felt and how the wind breathed through the trees. And the story of venturing out of the known into something dark and palpitating could not fail to appeal to a restless adolescent boy. It was as if this stranger was sharing secrets with me about everything that was most important in life—love, faith, terror, doubt—with such trembling intensity that I could do nothing but start whispering secrets back to him.

Lawrence uncovered parts of myself that even my closest friends or family could never have known were hidden within me. And as I started wandering out into the sunlit galaxy he had opened, other doors started flying open, as I entered Keats’s letters, and Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet, Graham Greene’s The Quiet American and, at this point, works by contemporaries that contrive to reorient my life every few months, so it seems, and leave an indelible mark on my soul (whether it’s Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance or Alice Munro’s latest collection of stories).

It’s easy these days to be distracted from the simple, complex explosive power of a book by all the more glamorous-seeming novelties winking around us. A YouTube video seems to bring Cuba home to us more vividly than any travel book could do. Tweets and updates and Instagrams flood in on us at such a rate that we hardly have time to sink into the private cathedrals of space and light erected by Henry James or Proust. The world is in such a rush right now that it’s tempting to think that it’s more important to be up-to-the-microsecond, on top of things, with the latest news streaming into one’s palm than in fact what renders us richest and most attractive as humans, the spacious, deepening, timeless world of books.

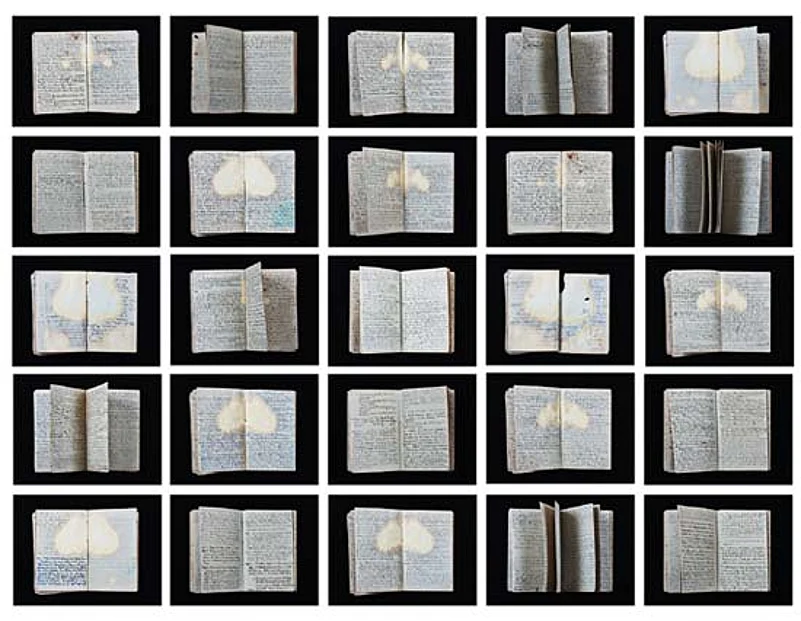

Inkpressed Chronicle 2013, a set of 25 photographs of a journal, by Sathyanand Mohan

That’s precisely why books are more urgent—and have the capacity to change our lives more radically—than ever before. SMSes bring us up to the surface of ourselves, books take us back down to the depths. CNN tells us what happened a minute ago, books remind us of what will happen next year, or decade, and open up a universe that stretches back through centuries. Anyone who breathes knows the difference between a quick “Hi, there!” and a breath-held, silent conversation in the dark—the reading experience—that can leave one upended, with tears in one’s eyes.

I often think, in fact, that it’s only books that allow me to bring to my life any depth of attention or purpose. In the two-room flat where I live in Japan, I try to take time, every day, to step away from the bombardment of e-mails and opportunities and papers around my desk, for an hour, and just sit on our 30-inch terrace in the sun, reading something sustaining, whether The Age of Innocence or the latest by Colm Toibin.

The minute I’m with the book—and it would be the same, of course, on a Kindle or any device, so long as I was lost in a long piece of narrative, and not a magazine or website—something in me slows down and opens up. I’m pulled out of cacophony, away from the one-liner or sound-bite, and into a much fuller world in which I learn to hear what’s not there and see what’s never shown. As a writer on place, I’ve learned to read cities by spending eight years of my youth learning to read books; as a husband and father, I feel the few things I know about human nature come not from TV or rock ’n roll, much though I love both, but from conversations with Maugham or Proust.

A book doesn’t have to be a literary classic, of course, to change us forever. As a little boy, I was introduced to the adventures of Paddington Bear. A small, bedraggled foreigner myself, I was so enchanted by the story of the unwashed visitor from Darkest Peru that I resolved to go to his homeland as soon as I could (and did so, the season I left high school). Tintin, Sherlock Holmes, Agatha Christie have all been lifelong friends to many. When my mother, then 81, was bedridden after surgery recently, I asked her what I could get from the pharmacy to help with the pain and she said, “A Wodehouse, any book by Wodehouse.”

Returning to India earlier this month, I had been wondering whether there was any point in spending long, often difficult hours at the desk, writing books that can increasingly feel like ships in a bottle flung into a black hole. If I were 19 today, I might love novels, but I probably would be slow to tear myself away from screens large and small, the instant excitement and gratification of Facebook, Tumblr, the latest video feed.

But then one woman told me she had changed her course in life after reading a book of mine I’d almost forgotten writing. Another said she’d gotten rid of her green card after encountering some sentences that came to her through me. One stranger after another approached, almost shaking, as I’ve seen them do to every author, and confessed that she knew me, or had enjoyed a conversation with me—even though we’d never met before. And it was true: each did know things about me from the page I’d have a hard time confessing to even my closest friend.

In so many countries I visit, there’s concern now that books, and with them the wider understanding, the deeper attention span, the sense of closeness and nuance they instruct us in, are fading; one of the many richnesses of India, its least gross national product, seems to be that bookshops, newborn publishers and dazzling new writers are everywhere, and probably a thousand different books have changed millions of different lives just in the time you’ve been reading this.

What I treasure most at any moment is intimacy, surprise, a sense of mystery, wit, depth and love. A handful of cherished friends offer me this, and the occasional singer or film-maker or artist. But my most reliable sources of electricity are Henry David Thoreau, Shakespeare, Melville and Emily Dickinson. News changes my life, only to unchange it a second later; books fling open a window through which one passes, never to return quite the person one was.

(Pico Iyer is the author of, most recently, The Man Within My Head, and just out from TED Books, The Art of Stillness.)