Bhikhaji Rustom Cama, born in 1861; Rukhmabai, born around 1864; Cornelia Sorabji, born in 1866: three remarkable women of late 19th century India. Chances are that the names of the first two will ring a bell. Madam Cama is associated with the unfurling of the first prototype of the Indian flag. Rukhmabai, one of India’s first woman doctors, was known also for resisting her marriage as a child to a much older man.

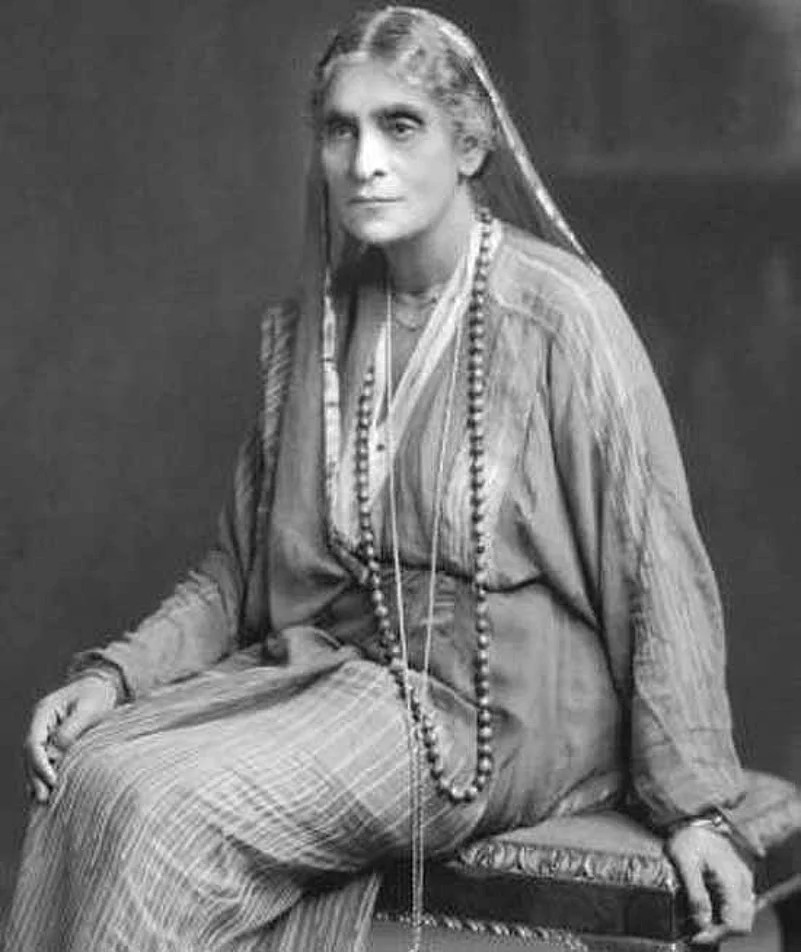

Cornelia Sorabji remains largely unacknowledged, although she too was extraordinary—the first woman to practice law in India and Britain, she was also possessed of an authorial voice that reflected intellectual depth, verbal felicity and keen powers of observation. It is useful to have this handsome volume, edited by Kenya-born and London-based author and doctor, Kusoom Vadgama, which puts together a selection of Sorabji’s prolific writing, including letters, diary entries and book excerpts.

Any editorial selection is ultimately subjective and limiting, but this book captures the broad contours of Sorabji’s life which spanned two extremes of the Raj: its zenith under a queen who ruled over a quarter of the world’s population, and its ultimate dissolution with India’s independence. The privileges and prejudices of this era marked Sorabji personally. A daughter of the Macaulayian Minute, she could access a professional education; strike deep friendships with the elite; and participate in the big debates of the day. Also, as she was a woman she had to wait 31 years after graduating in law to be called to the bar.

Victorian philanthropy gave Sorabji her first break in 1889 by opening the gates of Oxford’s Somerville Hall to her. She came to symbolise the Empire’s “civilising” mission. As an editorial of the time commented, it was hoped “her work may benefit her country women”.

Educating Cornelia was an investment that paid handsomely—not just for Indian women but for British interests. Her contribution was two-fold. First, by battling to be recognised as a professional and emerging as India’s first woman barrister, she broke through gender barriers. Second, she provided both visibility and legal assistance to a category known as the “purdahnashin”—women who lived behind the veil and who were invariably cheated of their entitlements and rights. Sorabji painstakingly documented their condition and drew up a ‘Scheme’ for their legal protection. In 1954, The Times, in its obituary on Sorabji, noted that “some 600 wives, widows, minor heirs and orphans have received the benefit of her advice”.

But Sorabji was no radical. In fact, she proved to be a doughty defender of the British status quo. Two months into her first visit, she was breathlessly writing home: “I see and hear so much to interest me in wonderful England and the people are so exceedingly kind.” As a student, she looked with a jaundiced eye on “all the Congress people” who talked “any amount of bosh”. In 1908, in a letter to an English friend, she writes, “When are you coming to see India? Come quickly before the new mutiny lays my bones with the defenders of the Empire”. In a diary entry of 1919, Sorabji revealed her deep distaste for the “inflammatory talk” of Tilak’s supporters. In 1926, participating in a royal assembly, she reports how the King’s personal flag made one “want to die for it”.

A November 1930 broadcast has her roundly stating that Gandhian methods for the “alleged attainment of self-government” are not justifiable and that “progressive self-government within the Empire” was the way to go. In a letter to the British home secretary in 1943, she suggests that Krishna Menon be “interned” and pleads, “Please help us. Loyal India as you know far outnumbers the self-regarding, personally ambitious politicians”. The year of India’s independence, 1947, saw Sorabji laid low by ill health. Posterity therefore is denied her view of this momentous turn of events.

By dredging a rich store of material from the Cornelia Sorabji archives in the British Library, Vadgama breathes life into an early Indian woman intellectual. There is a certain tragic thread that runs through this life. One senses in the words Sorabji poured out to friends and family an unending search for identity. A Christian of Parsee origin; an Anglophile who felt India was calling her; a woman feted in the Empire and derided in the colony; a singleton fated, as she remarked, to confine her affections to old men, Sorabji’s was not an easy life.

But if one were audacious enough to encapsulate it in one sentence, it would be this: Here was an extraordinary woman who found herself on the wrong side of history.

(The writer is director, Women’s Feature Service)