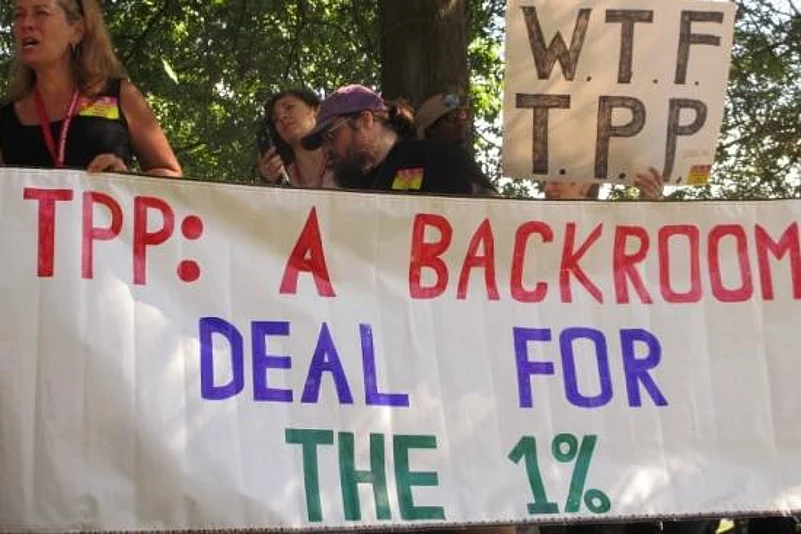

For almost 10 years now, 12 countries, led by the United States, have been negotiating a behind-closed-doors, wide-ranging, multi-nation trade agreement known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The Trans-Pacific Partnership covers a vast spectrum of trade-related issues, from agriculture and tariffs, competition policy and intellectual property. Because of its secretive nature, whatever actual details of the agreement that are now known, have come through leaks. One particularly important leak was of the intellectual property chapter, first published by Wikileaks last year, and updated last week. The TPP’s intellectual property chapter is of particular concern and alarm to the developing world and, in particular, to India.

Access to Medicines and Section 3(d) of the Indian Patent Act

As is well known, access to drugs and medicines worldwide is regulated by the legal regime of patents. A patent provides the owner of a drug the exclusive right to market it for a set period of time. This allows the owner to extract sufficient amount of profit to cover his research and development costs, and make the practice of developing medicines financially viable—or so it is argued. Since a patent essentially confers a monopoly upon the patent holder, and saves him from the vagaries of economic competition, it vests near-absolute pricing power in his hands. This has led to numerous criticisms highlighting the patent regime as the reason why essential and life-saving drugs are often priced beyond the reach of those who need them most—poor people in developing countries.

The availability of such potent market control, through patents, has led to a series of practices indulged in by big pharmaceutical companies, with the express goal of increasing the life of their patents even beyond their expiry dates. One particularly pernicious practice is known as “evergreening”. Normally, after a patent expires, generic drug companies enter the market, and prices are pushed down. “Evergreening”, however, refers to making minor modifications to a drug, and then claiming a new patent over the changed product—thus, effectively, extending monopoly control over the market. For instance, if I take out a 20-year patent on a drug and—in its 19th year—make a small change to its composition, and then take out another patent on the “new” product, I retain monopoly control over that drug for a full 40 years and—since there is no end to this practice—potentially forever. Prices, thus, continue to remain high.

This is where Section 3(d) of the Indian Patent Act comes in. Section 3(d) does not allow patents in cases of a “mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance or the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance.”

Section 3(d) was in the news last year, when Novartis initiated a high-profile litigation against the Union of India before the Supreme Court. Briefly, the Intellectual Property Appellate Board had rejected Novartis’ patent for the cancer medicine “Gleevec”, citing Section 3(d). In the Supreme Court, the question was what the meaning of “enhanced efficiency” was, under Section 3(d). The Court held that 3(d) envisaged that the efficiency must be related to the purpose of the product. In the case of medicines, therefore, the “new” drug must be “therapeutically more efficient” than its predecessor drug, on which the patent was going to expire. On this basis, the Supreme Court agreed with the IPAB and rejected Novartis’ claims for a patent.

Novartis had priced Gleevec at 2666 dollars per patient per month. Generic companies, on the other hand, were selling their version of the drug in the range of 200 dollars per patient per month—that is, at one-tenth the price. As IBN reported at the time, the fall was from Rs. 1.2 lakhs a month to Rs. 10,000 a month. This one example is enough to demonstrate the crucial role played by Section 3(d) in making medicines affordable.

Section 3(d) has been hailed for striking the complex balance between innovation on the one hand, and public health and access to medicine on the other. Through the use of provisions such as 3(d), and other mechanisms such as compulsory licensing, India has developed a reputation of being a “pharmacy to the world’s poor.” Its patent regime allows generic drug manufacturers to produce life-saving medicines at cheap rates, and serve both the domestic population, as well as export them to other developing countries at affordable prices.

The TPP’s End Run around Section 3(d)

Naturally, American big pharma is not happy. India’s IP regime has been constantly blacklisted by the office of the US Trade Representative, as well as by the US Chamber of Commerce. For its part, India has always maintained that its laws are compliant with its international obligations to the WTO, and the lack of any formal challenge within the WTO mechanism seems to suggest this is true.

Wikileaks’ revelations of the TPP’s intellectual property chapter highlight a particularly insidious attempt by the United States to undermine India’s patent regime. As the leaked draft shows, the United States has proposed a clause, which reads:

“A Party may not deny a patent solely on the basis that the product did not result in an enhanced efficacy of the known product when the applicant has set forth distinguishing features establishing that the invention is new, involves an inventive step, and is capable of industrial application.”

The use of same phrase—“enhanced efficacy”—that is used in Section 3(d), suggests that this is a particularly naked and blatant attempt to ensure that any signatory to the TPP will not be able to make use of such anti-evergreening measures. Effectively, the TPP illegalises Section 3(d) of the Indian Patent Act.

Why Should We Care?

One might well ask: India is not a negotiating party to the TPP, so why should we care? There is an immediate and practical reason, which is that it is quite possible (subject, of course, to correction) that under the TPP, signatory countries will be required to stop and confiscate Indian goods in transit to other countries, if they violate the TPP. This has happened before, most notoriously in 2011, when the EU initiated multiple seizures of life-saving Indian drugs that were being transported to Africa and Latin America. While the EU provision authorizing that has been subsequently amended (at the behest of India and Brazil), the Wikileaks revelations show that the United States has proposed, in the enforcement chapter of the TPP, vesting signatories with the power to take border measures for in-transit goods (the text does not seem to apply to patents, but its exact scope remains unclear).

However, there are other long-term reasons why we should care. The development of international law is never a unilateral process. It is through multinational treaties that norms are created, codified, and eventually entrenched. The negotiating countries to the TPP together account for 40% of the world’s GDP, and constitute a formidably powerful trading bloc. Other versions of the TPP, involving the EU, are already on the table. If India—and allied BRIC countries—are not careful, there might come a time when they find that they have no option but to opt into a world order that has created new, restrictive intellectual property norms, that have become far too entrenched to be reversed. This would be particularly tragic, given that only recently, India has been praised for its tough stance against the IP-bullying that has become a staple feature of the US Trade Representative’s Office.

But perhaps what is most alarming is that the TPP—despite its clear anti-3(d) stance, and its provisions for investor-state dispute resolution mechanisms, which will allow investors to sue States in international tribunals for TPP violations even if there is contrary domestic law like Section 3(d)—has met with approving voices from within the Indian establishment.

India has a long and proud history of crafting an alternative intellectual property regime, which has refused to sacrifice issues of public health and access to medicine upon the altars of corporate interests, while maintaining the basic requirements for innovation. It is a history that has inspired African and Latin American countries to take similar measures for their citizens (see, for example, the case of Argentina). It is this history—as well as the critically important present-day needs of billions of people—both Indian as well as global citizens—that agreements such as the TPP threaten to their very foundations. We would do well to be watchful.

Gautam Bhatia — @gautambhatia88 on Twitter — is a 2011 graduate of the National Law School of India University, and presently works at the Delhi High Court. He blogs about the Indian Constitution at http://indconlawphil. wordpress.com