Take a deep breath before you read this, and know that these are only scenarios—thumbnail sketches of what may happen. We cannot yet pluck the future out of the crystal ball, and the future may yet hold surprises. But yes, in one of the better worst-case scenarios out there, 100 million and more Indian jobs will be at risk during and after the COVID-19 lockdown stage. CII, a leading industry association, asked industry bosses how they felt things would pan out—of the 200 CEOs surveyed, one-third expected job losses of 15-30 per cent in their respective sectors. Another 47 per cent felt the figures might be slightly less than 15 per cent. But translated into actual numbers, the scenario still seems scary. Tot up the estimates of those likely to be unemployed in the various sectors, and it’s a horror movie coming to a screen—sorry, office—near you.

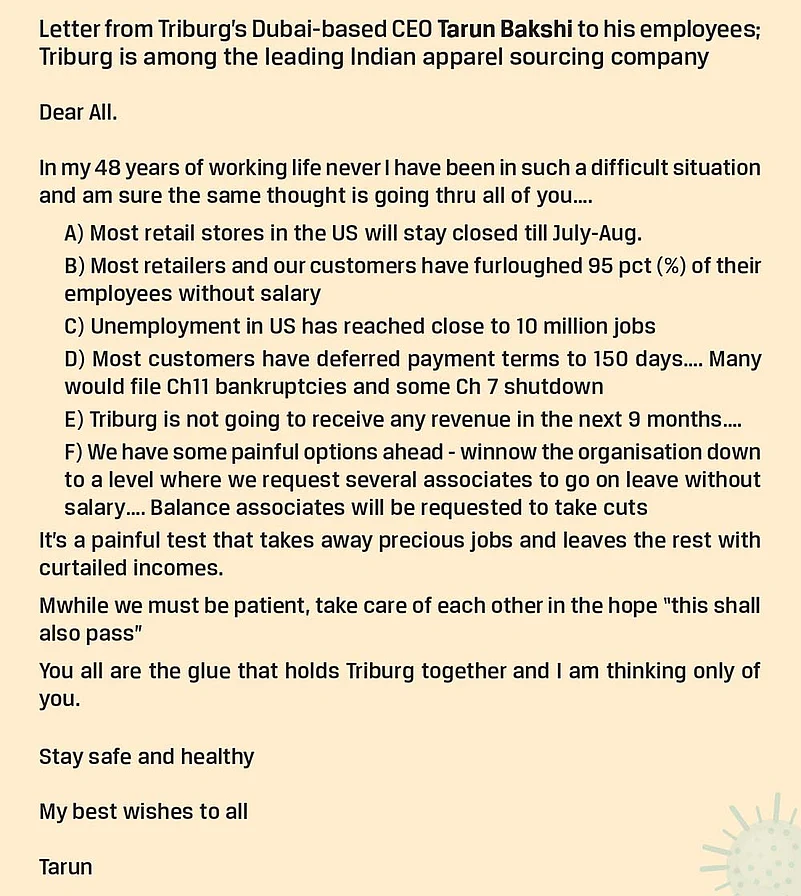

From end-March, most companies have resorted to one of these three decisions—sacking people, asking employees to go on indefinite leave without pay, and slashing salaries by as much as 85 per cent. Emotional and distressing emails about jobs and wage cuts were dispatched from their corner rooms by CEOs to employees, some of whom had worked in the same companies for decades. The Dubai-based CEO of Triburg, an apparel-sourcing firm, wrote, “In my 48 years of working life, I have never seen such a difficult situation....”

Those mercilessly pink-slipped are often too scared to even tell their families. “I don’t have the courage,” reveals Rohit Verma (name changed), who worked in the marketing division of Makino India, an auto-ancillary firm, and whose family includes his wife (homemaker), old parents and two children. Those who are at home are unsure if they will ever go back to their offices. “My owner gave Rs 7,000 in March, when the lockdown was announced. He assured us of future salaries, but I am not sure. I am not even sure about my job,” says Deepak Kumar, who operates a cloth-weaving machine at a garment firm.

Fortunately, there is also an optimistic scenario—indeed, that will most likely intersect with the more depressing tendencies to produce a complex reality. The usual picture of a shell-shocked economy with zero demand may be too simplistic. Yes, the pain of unemployment will be felt acutely over the next three to six months, but there can also be a quick rebound. In fact, the creation of fresh jobs and a return of old ones may happen sooner than we expect due to two reasons. The first is psychological: consumers, liberated after being cooped up at home for over five weeks, may go berserk once the lockdown is lifted. They may wish to buy more, spend more—certainly, travel more. It may be irrational, but very human to go overboard. Of course, this release of pent-up demand will be restricted to those who retain their jobs.

Brand expert Harish Bijoor offers a more concrete reason to feel optimistic. He says that although Goldman Sachs and World Bank have predicted the world economy could witness a negative growth of up to 3 per cent, and India to grow at a mere 1.5-1.6 per cent, the latter may not be true. India is less dependent on exports compared to China and Japan, he points out, and has a huge domestic demand—so growth may “remain static” around 4-5 per cent. In addition, economic crises in countries like India tend to boost labour productivity.

Ultimately, it will be a toss-up between three scenarios—a V-shaped recovery, a U-shaped one or an L-shaped one. US President Donald Trump has categorically talked about the first—saying that the US and other economies will immediately rebound once the lockdowns are lifted, and, hence, there will be minimal unemployment and higher-than-estimated growths. Most experts are nervy and apprehensive: they believe the U-shaped scenario to be more likely, and expect the lower plateau to last for anything from six months to a few years.

Only if the IMF’s dire prediction turns out true—which is that the COVID-19 crisis will be the worst after the Great Depression of the 1930s—will we be staring at the dismal L-shape spreading across the globe. That is, once growth plummets across countries, it will hug that low level for several years. In the case of the Great Depression, this trend lasted for over a decade. In such a situation, expect job losses in India to be nearer to 200 million, besides a long-lasting, severe impact on everything and everyone related to farming.

Hundreds of migrant workers—jobless, homeless and almost without cash and food—gathered outside a Bandra railway station in Mumbai following rumours that train services would resume on April 15.

However, there are too many ifs and buts here. No one has seen such a scenario before—and we don’t know if the recovery will be V-shaped, U-shaped or L-shaped (those are just shapes in a nervous Lego toy game we are playing right now). We don’t even know if we can compare across a century. The Great Depression was caused by huge and deep-rooted systemic problems that were accentuated by entrepreneurs, central bankers, policymakers and investors. This crisis is the result of an external shock; the state of most economies was within the range of normal, if not exactly in the pink of health. Hence, how the economies, consumers and entrepreneurs react is still in the realm of speculation and educated guesswork.

But right now, it’s as stark as either/or. Saiful Haq, a property developer in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, laments that given the jobs and wage losses, he does not know if property buyers will be in a position to repay their loans. As it is, real estate tends to dip during the monsoon season. But Raju John, director general, Builders Association of India, also points to the eventual, but inevitable, climb-back of activity: “After the lockdown, it will take a few weeks to get the workforce back, and streamline the machinery and raw material. There will also be a rush to complete pending projects.”

Similarly, in the extreme scenarios now painted, there seems to be no hope for the travel and hospitality segments. Most experts feel they will be decimated with job losses, bankruptcies and shutdowns. Let’s also look at the hopeful side. There are tens of thousands of people stranded across the globe—home or away, at their origins or midway. There will also be untold thousands who would now wish to visit their family—after not having been able to be with them in times of deep uncertainty. People may be afraid of travel, but they may also want to move, as if freed from prison. Post-lockdown, the sales of air tickets may zoom, as may their prices; the related spike in demand may shore up the hospitality sector too.

The situation in agriculture is more complex. The overall amount of work that needs to be done is, roughly speaking, constant within a short time-frame—but this is a dynamic, mobile field of employment that faces unique bottlenecks now. Farmers are sitting on a bumper rabi crop, although there are indications of a 15-20 per cent loss in wheat production due to untimely rain. But there is a shortage of labour, which moves from UP-Bihar to Punjab-Haryana, and also of mechanical harvesters, which move from Punjab-Haryana to UP. The lucky part: a portion of migrant families, who go back to their villages and do odd jobs during this season, are available as farm labourers. “Earlier, these migrant labourers would refuse farm work back home at Rs 300 per day. Now, as they cannot do those odd jobs they do in normal times, they are willing to work for Rs 200,” says a farmer, who owns an acre in western UP. “But supply is low. There were instances of workers being smuggled from Haryana to UP after payment of bribes at the borders.”

Employment is one facet of a complex farm scenario where the economic impact on individuals will be across levels. It’s a chain effect. Take one of the acute problems right now: farmers’ access to mandis. “They have few options: transportation is hit. There are added costs as they will first take their crops to (the nearest) storage facilities, and only later to the markets,” explains Yoginder K. Alagh, agri economist and vice-chairman, Sardar Patel Institute of Economic and Social Research, Ahmedabad. Also, allied segments like dairy and poultry have also taken a severe hit. The result: shrinking incomes. For farmers, warehouse receipts of their crops are not bankable or cashable. Until and unless they sell their crops, they cannot earn money to repay the loans taken earlier to buy seeds and fertilisers, and run their households. The crisis is accentuated because of the hit on all the modes of additional income. To finance the next crop, the farmers may have to take fresh loans, even if they have been unable to repay the earlier ones. This will result in a classic debt trap that can last several seasons.

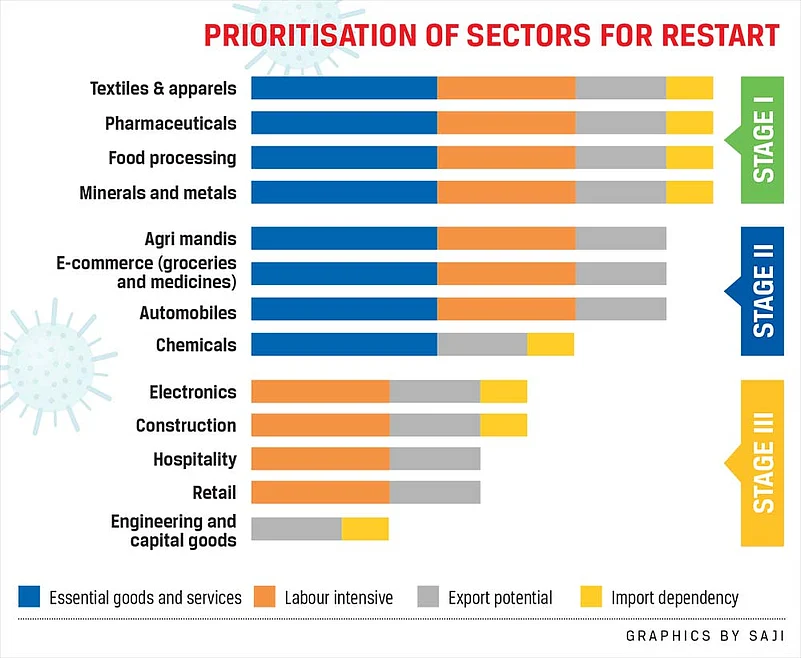

Given these uncertainties about how things will pan out in terms of jobs and economic recovery in the post-lockdown period, a lot will depend on what crisis management measures the various state governments will adopt—what CII calls a “calibrated and safe exit from the lockdown”. To ensure the least harm, and speedier recovery, the government will have to decide which sectors to restart, in what phases—how the economic imperatives are to be matched against workers’ safety, and getting back migrant workers.

The CII feels both the clauses ‘labour-intensive’ and ‘essential’ should apply in choosing sectors: thus textiles, pharmaceuticals and minerals should be opened initially, followed immediately by agri-markets, e-commerce, automobiles and chemicals. All the remaining sectors should be opened in Stage 3. The entire economy should be up-and-running within four to five weeks, with adequate attention paid to safety protocols and social distancing between workers.

However, experts disagree with this approach. K.E. Raghunathan, former national president, AIMO, says unlocking a few sectors “without their supply chains and logistics restored” will defeat the objective. “How will it help if my retailer cannot sell the goods?” he asks. Narendar Pani of the National Institute of Advanced Studies feels the government has to initially identify crucial manufacturing hubs, open them, woo workers back and ease their supply chains.

A constant focus in this process has to be on the employees, on how to ease the pain for them. Almost 40 per cent of migrant labour in the informal economy—seasonal and circular migrants—are facing hardship, even hunger. “Workers are stuck and don’t have cash. They need to work to survive,” says Abha Mishra of Ajeevika Bureau, a workers’ collective that provides legal and health aid and financial literacy. “The contractors employing them are also affected. I am not sure if they’ll be able to absorb all the workers once the lockdown ends.”

Entrepreneurs in the organised sector are in a tizzy too. It’s only after the lockdown is lifted that they can take stock of their factories—the safety of machines, usability of raw materials, inventory of finished products etc. There is no certainty about being able to execute pending orders straightaway. Into this mix comes the uncertainty about employees. Raghunathan says the entrepreneur is not sure if his workers will even return. It is estimated that between 50-65 per cent may not, at least not immediately, due to the continuing scare about the virus.

Given these fears, among both employers and employees, it isn’t unusual to see the former clamour for government support. For example, the garment sector says it cannot revive for 9-12 months, and needs help in the first 2-3 months to enable it to survive and protect livelihoods. Similar voices are heard from other sectors too. “Industry is under pressure, and the irony is that the government hasn’t announced any economic package,” says a corporate CEO. “Our stocks can last for another month in the post-lockdown scenario, but demand slowdown will be the killing factor.”

What people tend to forget is that a government stimulus package isn’t enough. Even during the pre-pandemic slowdown, decisions by the finance ministry to help India Inc weren’t exactly producing great results. Some recent research even goes contrary to the popular notion and says huge government spending during the Great Depression actually prolonged it by a few years. Reason: it created employment, but did not add to economic growth. This time, the government has to tackle both, and attack demand and supply at the same time.

The positive lies in the fact that several government measures can boost consumer sentiment locally, and make up for the lack of demand for Indian exports. Given that imports are cheap due to low global demand, Indian industry can become competitive and profitably sell goods in the domestic market. China, whose economy seems to have come out of COVID-19, plans to do the same. Like China became the engine for global growth after the financial crisis of 2008 through exports, India and China can do the same this time through higher sales in their respective local markets.

But the macro picture will always average out and show signs of stabilising—and at the same time hide real human pain at the level of ordinary life. “The important concern is loss of employment and income. It’s a pity the government failed to understand this,” says Ravi Srivastava, labour expert at JNU. It needs to keep this in mind now—for disaggregated human pain is not just a marker of social health, it also becomes an economic and political fact. “Yes, it is true that life is more important than livelihood,” explains Pani. “But we’re fast reaching a point where life itself can be threatened due to lack of incomes and wages.” He is one of those who fears things may get worse after the lockdown is lifted on May 3, before the economy picks up. That, in some ways, the cure may have been worse than the disease. India will know soon.

***

38 million or 70 per cent of jobs at risk in the tourism industry, as estimated by KPMG, a global think-tank

10 million Jobs at risk in the entire textile chain, if there is no government-driven stimulus package

A bulk of the 136 million jobs in segments with casual workers and unwritten contracts, and self-employed areas are at extreme risk

That risk is very real in all segments where informal employees make up a huge percentage, such as manufacturing (76 per cent as per Periodic Labour Force Survey, 2017-18), financial services (50 per cent) and public sector (55 per cent)

In agriculture one may witness a debt-creating paralysis: farmers being either unable to harvest their crops, or to reach mandis in time, leaving them indebted for the next few seasons

***

Employment

14.5 lakh E-commerce

69.9 lakh Food processing

474 lakh Retail

500 lakh Tourism

662 lakh Building construction

****

Pavan Kumar Vijay

CS & Founder, Corporate Professionals

The courts are closed, companies are not working, and a lot of compliance dates were pushed forward, so we have negligible work. Being a consultancy firm, we have a hand-to-mouth model. We get payments from clients on regular intervals or draw overdraft from our bank. I have paid salaries to my 80 employees, including 60 lawyers, for March, but no new work has come up, and even the big clients have not paid for previous work. I like to remain positive, but, realistically, the impact won’t go away for at least a year. We are not cutting wages of the support staff. The consultancy staff has been asked to go on leave without pay for three months, and opt for a skill upgradation course, which we would support.

Rachel Goenka

Founder & CEO, The Chocolate Spoon Company

The restaurant business has been hit in the worst possible way. In the absence of a government package or support, I am afraid we won’t be able to pay our staff for long. We are operating with limited in-house delivery. Around 30 of the 430 employees are working to sustain this. I don’t see anything getting back to normal. You have the monsoon coming next. That would be another pain.

Shilpa Harit

Owner, Style Your Way Boutique

We are passing through a very bad phase, with zero sales for a month now and overdue mall rentals. For April, I have no means to pay the eight employees. My karigars (employees) have not gone back home. But I call each one every 3-4 days. I have 1,000-1,500 customers in and around Gurgaon. I plan to reach out to them with a ‘Help us now, collect your dresses later’ kind of Facebook campaign.

Nikunj Sanghi

MD & Founder, JS 4Wheel Motor Pvt Ltd

We are almost completely shut. There is absolutely zero cash. Probably 2-3 per cent business is operational. I have paid salaries for April. In fact, 90 per cent of car dealerships have done that. Our business model is based on a low margin—it is almost like earning daily wages. If revenue is zero, how are we going to sustain beyond April?

Disha Grover

Founder, Nutrifit by Disha (New Delhi)

Mine is a self-owned, self-operated, single-branch clinic. I have run it for the past three years. This lockdown has yielded mixed results. The bright side is that people are indoors. They are able to take time out from their schedule. We were running ‘online diet plans’ and have migrated some of our existing clients to the online platform. Our profits are not huge, but I can protect the jobs. I don’t plan to fire anybody.

Riyaz Ismail

Director, Madras Bakers Pvt Ltd

We were really surprised when after the Janata Curfew on March 22, 25 out-of-state workers in our centralised baking station sensed that a longer lockdown was coming any time and took the last train out of Chennai to their native places in Bihar and UP. After the Chennai Corporation permitted bakeries to operate from April 12, we have been managing with just five local workers, who are able to bake only 600 loaves of bread. Earlier, we used to bake 2,000 every day. The other workers have called and said they will return after the lockdown is over, which is some solace as we would otherwise have to hire fresh hands and train them from scratch.

Bijender Singh Dalal

Chairman, Pragatisheel Kisan Club, Palwal (Haryana)

Vegetables and flowers seem to be thriving this season due to clear air and better water from the canal. As unexpected rain led to discolouration of the wheat harvest, we were banking on our exotic range of flowers and vegetables. Due to the lockdown, however, floriculturists, who used to sell Rs 1 crore to Rs 1.5 crore worth of flowers daily, have had to face losses—the flowers wilted before they could reach the Gazipur wholesale market in Delhi. Some of us adopted new technologies to improve the quality and quantity of yields, but limited access to export markets has caused distress. Once the market opens, we expect higher prices will help recoup the losses.

—with inputs from Himanshu Kakkar and G.C. Shekhar