The television set plays the news on mute at a microfinance executive’s home in Noida. A prime-time panel of experts is having a spirited debate about an exit strategy—how to ease coronavirus restrictions, find a way out of the pandemic, and revive the battered economy. The executive watches silently, without blinking, eyes glued to the ticker scroll running at the bottom of the screen. The branch manager of a microfinance company and his field officer were assaulted and arrested in Sarangarh district of Chhattisgarh for breaching stay-at-home orders. They were trying to recommence field operations of lending and collection of dues. Another such assault was reported from West Bengal. At the heart of any revival plan is the nation’s microfinance market, the largest in the world, catering to more than 120 million homes that have no access to financial services. Indian micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and the farm sector are the biggest beneficiaries of the microfinance institutions (MFI). And these sectors have clearly suffered a one-two punch and cannot afford any missteps. But instructions from the Centre and states to let MFIs resume limited operations aren’t clearly percolating down to local administrations. The Chhattisgarh and Bengal cases are grim reminders.

As the uncertainty over the lockdown extending beyond May 3, raising fears of more wage, job and business losses, the RBI recently offered a ray of hope with its second tranche of liquidity and regulatory measures. The package offers a special refinancing facility of Rs 50,000 crore to NABARD, SIDBI and NHB. This raised optimism for businesses and agriculturists seeking funds. But will that be enough for thousands of MSMEs, local businesses and the agriculture sector to restart operations after shuttering their doors for more than 40 days?

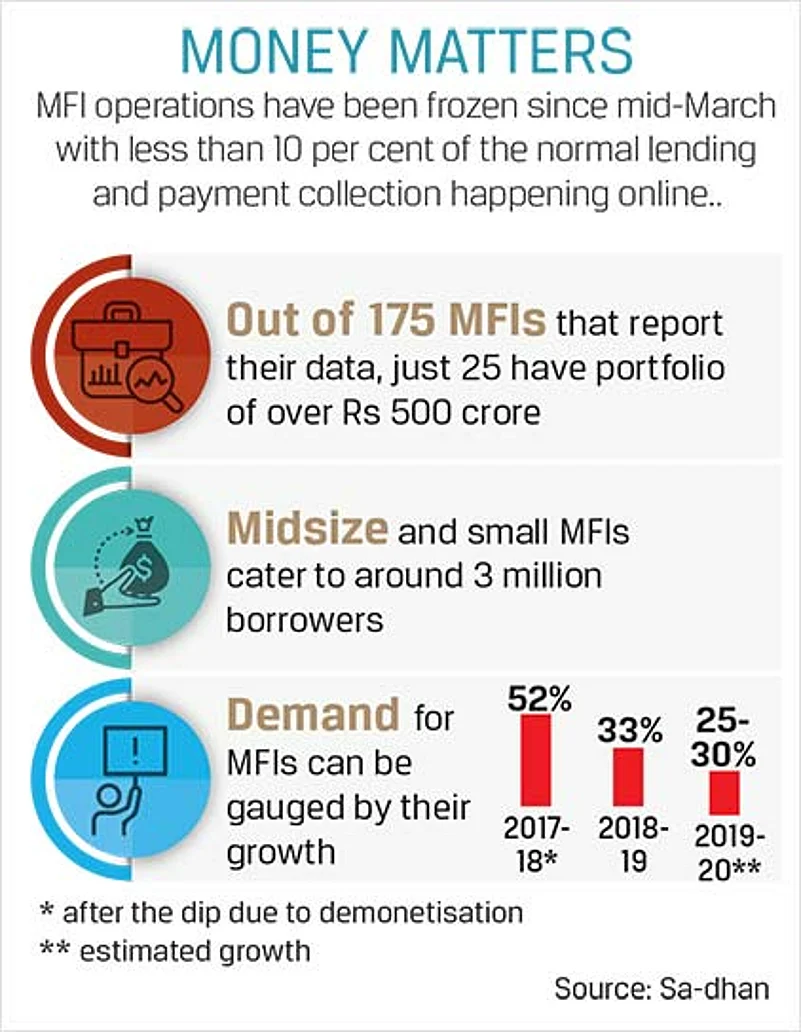

Incomes have dried up and people are dipping into their savings to remain afloat. The MFIs are one of the intended beneficiaries of the RBI’s move with 10 per cent of the targeted long-term repo operations funds raised by banks earmarked for them. This is expected to help a cross-section of businesses and individuals lacking access to banks. However, P. Satish, executive director of Sa-dhan, an umbrella organisation of MFIs, is unhappy that the RBI largesse will not benefit a large number of their members who serve the most deprived. “As the RBI has made investment grade paper floated by MFIs a condition to avail the earmarked funds, it will benefit only the top half a dozen MFIs that fulfil the criteria of having investment grade rating,” says Satish. That means the bulk of MFIs will be excluded. Of the 145 MFIs that are Sa-dhan members, about 95 have an asset size of Rs 200 crore or below, but they cater to nearly 3 million clients.

“Pooling of assets across a range of investment grades will be required so that a wide set of institutions can avail of this fund,” says Mathew Titus, managing partner at Market and EcoSystem Advisory and an MFI expert. Encouraged, however, by the RBI governor’s statement that “he will do whatever it takes” to push credit off-take and boost economic growth, Titus is hopeful that more will be done to help the MFI sector, which fulfils many needs, including one of the most critical—consumption smoothening.

According to KPMG in India analysis, this industry has evolved over the past two decades and reached over 25 per cent penetration level in the total addressable market in 2019. Microfinance lenders aim to provide easy access to formal credit to customers who need it the most and would not typically be eligible for bank credit. A vast majority of borrowers are women just above the poverty line and striving to improve their household’s living conditions. The critical importance of MFIs in uplifting the financially excluded “is evident from their contribution to improving financial inclusion, particularly in semi-urban and rural locations,” states a recent KPMG report, which also points out that the microfinance loan portfolio (35 per cent) is the highest in eastern and northeastern India. MFIs are also the largest contributor of new-to-credit customers among banks, SFBs and NBFCs.

Satish points out that people in some rural areas tend to depend on MFIs to get funds due to lack of access to banks. The need for MFIs is critical at this juncture as MSMEs, self-employed, casual labour and people engaged in agriculture-related activities would have drawn heavily from their savings due to the impact of lockdown.

Harsh Shrivastava, CEO, MicroFinance Institutions Network, hopes banks will pass on the benefits of lower interest rates to MFIs so they can pass it on to their borrowers. But he is also apprehensive because the moratorium of three months announced by the RBI was not extended by some banks to MFIs. “We have been requesting all banks to support the industry at this critical time. It is only fair to pass on the benefits to MFIs as they have already committed to support their own BOP borrowers with the same,” says Shrivastava.

The high interest rates charged by many MFIs remain a concern. After the RBI stepped in a few years ago, the bigger MFIs have been charging around 18-19 per cent interest, while the small and medium size ones charge around 22-24 per cent. Veterans say this is due to the interest rates MFIs have to pay the banks and the cost of operations, including collection of interest and repayments.

For most MFIs, the ticket size is Rs 30,000 to Rs 50,000 and EMI is dependent on what schedule a borrower adopts—daily, weekly or monthly. The EMI usually ranges from Rs 2,000 to Rs 3,000 with repayment time of one to two years, explains Rakesh Kumar, executive director and CEO, Light Micro Finance Pvt Ltd. “The biggest challenge is that the collection cannot be done digitally, unlike in urban India,” says Kumar. In rural India, collection by MFIs is still done door to door through agents, which has stopped due to the lockdown. “Some MFIs managed to collect their March installment, but not April onwards,” he adds.

Ramesh Arunachalam, an international development finance expert, says the RBI should appoint a broad-based special national committee with executive powers, comprising civil society, independent domain experts and other stakeholders, to monitor and evaluate the real-time effectiveness of its various instruments and measures. “This will help provide on-course corrections as well as enhance the effectiveness of implementation of various measures, especially by identifying and removing bottlenecks in real time,” says Arunachalam, who also stresses the need for making working capital and term loans available to MSMEs at reduced interest rates, with the RBI rate cuts being passed on fully.

In the normal course, the first quarter of the year used to see less uptake of credit, except in the case of banks predominantly lending to the agriculture sector. Khariff lending used to start in the last week of May or the first week of June, while non-agriculture lending would pick up only after July. But due to the lockdown impact, demand for loans from the unorganised and informal sector, non-agricultural sector, animal husbandry and other farm-related sectors is expected to pick up sooner this year.

Data collected by Sa-dhan shows credit demand during the lockdown period was almost 90 per cent lower than what is normal in March. During the first part of April, apart from digital transactions, credit off-take was less than 10 per cent of what is normal. This is at a time when harvest activities are in full swing and work for the next season’s sowing begins.