It is a pleasant April morning in Kashmir. The temperature swings between a comfortable 14 and 20 degrees Celsius and the towering Zabarwan range shimmers in the glassy waters of the Dal Lake. But Mohammad Shafi Sheikh, 52, who plies shikaras on the Dal, is distressed. “In the past few years, there were lots of tourists, but this year has been bad. No one is coming and we don’t earn anything. I don’t know what has happened this year,” he laments.

His colleague, Ghulam Mohideen, interjects, “Pulwama happened this year. After that, travellers stopped visiting. Only tourists from some countries are coming,” he says pointing to two ladies from Southeast Asia. In recent years, tourists from the region have been visiting Kashmir in significant numbers.

Nearby Ajaz Ahmad Kotroo, 43, relaxes on the deck of Pigeon, one of the oldest houseboats on the lake. Although he has not hosted any tourists in the past few weeks, he is positive. In three decades, Kashmir has gone through many such slumps and emerged out of those, he claims. “Tourism comprises seven per cent of our economy. Even without it, we will survive,” he declares with a smile. “Tourism will flourish in the Valley when you make it conflict-neutral. For long, the government has been linking tourism with peace and consequently, after every untoward event, it is the first industry to get derailed and last to return on track.”

Kotroo’s houseboat is behind Hotel Leeward. In 1996, when only 375 tourists visited Kashmir, the CRPF occupied the building and has stayed put since. Nobel Laureate V.S. Naipaul stayed in the second storey of the property in 1962. In his travelogue An Area of Darkness, Naipaul referred to the hotel as “Doll’s House on the Dal Lake”. The edifice now has bunkers on all sides and concertina wires on the walls. Armed men patrol the compound and motorboats ferry security personnel.

“The drop in tourist arrivals this year is unprecedented,” remarks Asif Iqbal Burza, director of Ahad Hotels and Restaurants. “A negative perception has been created that this place is not safe. The absence of tourists has nothing to do with the recession in the economy or the elections across the country. Other tourist destinations are thriving. Why would the recession and elections hit us alone?” he says. Burza runs luxury lodges in Gulmarg and Pahalgam. In the latter, a few hotels have shut down.

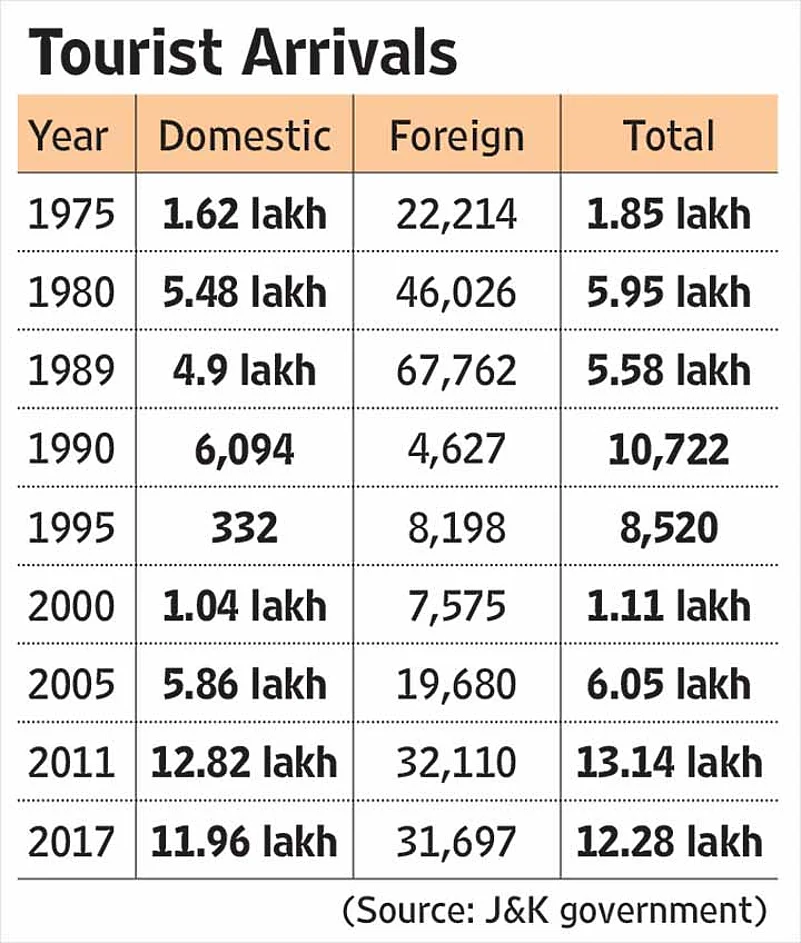

Hoteliers in the Valley compare the present crisis to that of the early 90s. In 1988, 7.22 lakh travellers, including 59,938 from abroad, came to Kashmir. 1989 saw the highest number of international arrivals—67,762. Most of them came from Europe and the USA. In 1990, as mass uprisings and armed insurgency broke out in the Valley, the number of tourists went down to 10,772. Remarkably, half of them were foreigners headed for Gulmarg for skiing in winter. There was a revival of sorts, when 2 lakh tourists thronged the Valley in 1999, but a decline ensued subsequently. 2005 was a remarkable year for tourism—6.05 lakh people visited Kashmir. In the following years, tourist arrivals kept rising.

Abdul Wahid Malik, president of Kashmir Hotel and Restaurant Association, claims that the influx of tourists transformed the Valley’s economy: “We opened up many guest houses. Kashmir only had 16,000 rooms in the 90s, but now, we have 55,000 rooms. Lakhs of people are associated with this sector. There are thousands of handicraft shops—all dependent upon tourism.” After a pause, he adds, “But the present situation looks scary. Some hoteliers are shutting down their properties and some are turning them into hospitals. Things have never been so gloomy.” IAS officer-turned-politician Shah Faesal quipped that the present distress in the tourism industry would turn Kashmir from a hospitality-driven economy to a hospital-driven economy.

Remarkably, two large-scale uprisings in 2008 and 2010—in which nearly 200 civilian protesters were killed and thousands others wounded—did not dent tourist inflow. In 2011, tourist arrivals crossed the million mark for the first time. The next year, 13 lakh tourists, including 29,143 foreigners, enjoyed the delights of the Valley. Last year, foreign arrivals touched 56,029— most from Southeast Asia.

As the numbers grew, so did the investment in the tourism sector. Hospitality chains such as ITC, Taj, Sheraton, Sarovar and Lemon Tree established hotels in the state. The government spruced up Gulmarg, Tangmarg and Sonmarg with large-scale infrastructure projects and began exploring the possibility of establishing new tourist destinations.

Ashfaq Ahmad Dug, president of Kashmir Travel Agents Association, says that after the September 2014 floods in the Valley, tourist numbers came down. Since then, travel agents and government officials are hosting road shows and marketing events across the country, especially in Maharashtra, Gujarat and West Bengal, to reinforce the fact that tourists are safe in Kashmir. Dug stresses that tourism in Kashmir is an economic activity and shouldn’t be seen as a barometer of peace. “Here, there are no crimes against visitors,” Dug declares. “It is the safest place for tourists, but still, a negative perception has been created on social media after the Pulwama incident. It is hurting tourism terribly.”

After the Pulwama attack, the governor of Meghalaya, Tathagata Roy, exhorted people to completely boycott Kashmir. His tweet read, “An appeal from a retired colonel of the Indian Army: Don’t visit Kashmir, don’t go to Amarnath for the next 2 years. Don’t buy articles from Kashmir emporia or Kashmiri tradesman who come every winter. Boycott everything Kashmiri. I am inclined to agree (sic).” Faiz Bakshi, MD of Shangrilla Hotels, says that travel agents who recently visited the Valley claimed that as part of a whispering campaign against the state, many of their peers were asked to not encourage tourism in Kashmir.

Officials in the tourism department of Jammu and Kashmir have not disclosed the statistics on tourist arrivals in 2019. However, they agree that the industry is beset by a massive crisis and slump. “We haven’t seen many tourists this year,” says a senior official.

“The current crisis is different. After Pulwama, there has been a coordinated attempt to isolate Kashmir and strangle its tourism sector,” says Rouf Tramboo, a well-known trekker from the valley. “Tourism helps a lot of people—there are guiding services, taxis, hotels, huts outsourced to self-help groups and tourism facilitations centres, all of which employ locals. People in the tourism industry are on the verge of unemployment. Airfares are soaring, no special trains are being run and there are no incentives for the tourism sector. This is a campaign to boycott Kashmir.”

By Naseer Ganai in Srinagar