Somewhere along the switchbacks seesawing to Māwsynrām, the menu at Samantha and Oomnen’s ‘5 Star Resturan’ is as much an oddball as the couple—it’s quite a story about how a tiny Khasi woman domesticated a wandering hulk from Kerala. That’s another time; this is a food story. Their food is fused with reciprocal love: a crisp dosa paired with tungrymbai and tungtap, Khasi fermented soy beans and a fish mash of punchy flavour and texture. The sambar and coconut chutney are seasonal/optional, leaning on supplies reaching this wet, wet world in Meghalaya. Pozhudhu sadam, the southern curd rice, accompanies a bowl of dohneiiong, pork chunks in a viscous curry of black sesame seeds. When the winter draught peeks through cracks in the shack’s wainscoting, they serve meals in insulated poly-casseroles. Fermented food tastes best in room temperature, they say. Not hot, not cold.

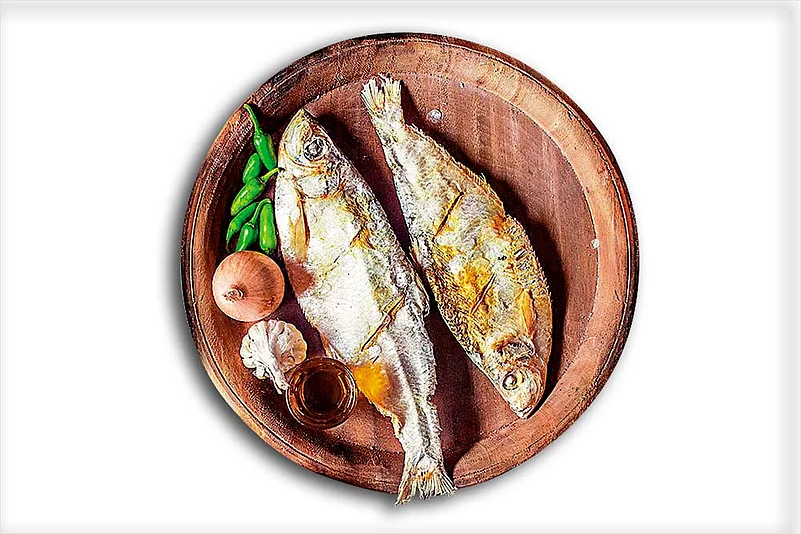

In another land—when the dehydrating loo blows—the cooling effect is the main draw at Ayandrali Dutta’s Noida home on a summer afternoon. You can’t escape the heady smell of mustard oil and fermented rice as you step in. “This is pokhala bhat of Odisha. It keeps the tummy cool during the summer months,” says home chef Dutta, serving an age-old coolant from the humid eastern and northeastern India with mashed potatoes and chopped onions drizzled in mustard oil, fried fish, roasted tomatoes, mango chutney and the condiment kasundi. She calls fermented food not just part of the diet, but a traditional medicine as well.

For long, well-slept rice has been a popular summer staple in India’s east and northeast—poita bhat in Assam, panta bhat in West Bengal, pokhala in Odisha, or bhotal bhat in Jharkhand. “Leftover rice kept in water overnight for fermentation turns into something like a stock,” say Madhushree and Anindya Sunder Basu, a food blogger couple from Calcutta. “It is like a Buddha bowl. We can enjoy it whichever way we want it.” It is high on nutrition as bacteria break down the complex components of the food, making it easy to digest.

Fermentation, fermented food: this is the latest big culinary trend, the type that’s getting attention from foodies lately. There has been a huge awakening in the past couple of years with the way people approach food—not the precise and visually arresting cooking of TV shows/celebrity chefs, the hypochondriac types, the toffee-nosed picky eaters of locavore novelty, the prying YouTubers dredging up overlooked cuisines and techniques. But those simple trencher-people, the knowledgeable folks who know how the food is produced. What and how to eat better, eat healthy.

And there’s such a huge ferment to explore in India; this hot pot of a nation offers a culinary variety as diverse as its cultures, religions and people. In a rice-intensive economy like ours, fermented rice, vegetables and legumes are well-known. Idlis, dosas, bhapa (steamed) pithas, shoru chakli (rice and dal pancakes), kanji (drink made from fermented carrots), kadhi, dhokla, khaman, vadi, vada, bhatura, jalebi, fermented bamboo, vegetables like gundruk, sinki and soybeans, yeast-fermented bread like naan or sourdough, fish, meats, and fruit wines and beers under the common name toddy have been there in Indian cuisine for ages.

In Bengal, Bangladesh and the Northeast, shidol (fermented anchovies) is a delicacy, as are fermented meats. Nona-ilish or fermented hilsa is a famous non-vegetarian delight. When wild game was available, venison was never eaten fresh in Assam and Bengal. It was left to ferment before being cooked. Fermented bamboo forms a large part of the northeastern repertoire and some parts of Bengal too. In Bengal, date palm juice (khejur rosh) is gulped down fresh early morning because it ferments quickly with the rising sun and becomes the intoxicating tari (toddy). Those pursuing hallucinogenic chemicals like to drink it from a well-sunned clay pot!

Panta bhat and side dishes in Ayandrali Dutta’s Noida home.

Okay, pokhala, panta, poita, bure or pani bhat are known victuals—the same rice recipe, soaked overnight—consumed by millions in five regions of eastern India. If you are a real ‘enthu-cutlet’, try this: phan pyut rotten potatoes; bekang or tungrymbai (soy beans); khorisa, u-soi, iromba, or bashchuri (bamboo shoots); or ngari, hentak, tungtap, or nona ilish (strongly fishy); or sa-um pork served with rice. Or, kosoi bwtwi, the Tripuri French beans with fermented fish. Get a bowl of gundruk greens, or Nepali kimchi, on the side and chase them all down with jonga— the Rabha tribe’s drink of the heavens, deliverer of the bacchanalian spirit.

This is fringe food, and the choice is yours. What do you want—food that simply palliates hunger (dal, roti, chawal), or the organoleptic yak cheese in the high Himalayas that stimulates the senses, or akhuni of the ammonia-like flavour from Nagaland?

So, has the final storming of the last untrademarked food begun? Yes and no. Nutritionists, food bloggers, chefs are bringing back fermented food to the table. According to the Godrej Food Trends Report 2019, fermented food is slated as the next big thing. And it is gaining popularity—from restaurants to grocer’s racks, with a wide range of products— as people are realising its inherent probiotic benefits. “The new generation has curd and buttermilk as a habit. Kombucha tea had made a good start in India. People are also taking apple cider vinegar for health reasons,” says Sangeeta Khanna, Delhi-based nutrition consultant. A regular supply of good bacteria via fermented foods is no longer optional, but has become a necessity, to help restore natural health, says nutritionist Kavita Devgan, also from Delhi.

Restaurants and chefs are experimenting and offering specialised menus. “People come to the restaurant and ask for dishes made of fermented ingredients. Though people dine out a lot, they are health conscious too,” says chef Avanish Jain of Radisson Blu, Faridabad. Miso, fermented black beans, tobanjan, gochujang, soy sauce and fermented tofu are common ingredients in grocery stores and home pantries these days. Other than kombucha and kefir, healthy drinks like pineapple tepache—“sweet, light and stimulating…a brew made of fermented pineapple peels”— are winning hearts, affirms Mumbai-based chef Reetu Uday Kugaji. Chef Priyank Singh Chouhan of Shiro, a Pan-Asian restaurant in Bangalore says, “Korean, Vietnamese, Japanese, Indonesian or Chinese…they all have different ways of food fermentation. Nowadays, the preparations and processes are varied to create the best gastronomical experience with modern intakes to provide good flavours, textures, presentations, balance and healthy options.”

But chef Gaggan Anand begs to differ. “I don’t think it makes sense to be served as a dish,” he says. “Can we call an achaar a cuisine or a kanji a dish? Fermentation is a process that can add value to a dish, but not an end product.” Moreover, processed fermented foods are not healthy. “Good fermented foods are those cured through a natural process, devoid of artificial flavours, additives, flavouring agents,” says Luke Coutinho, Goa-based holistic lifestyle coach. Besides, some fermented products contain high levels of added sugar, salt and fat. Also, products that use yeast for fermentation should be consumed with caution.

Chef Avanish Jain is more than happy to rustle up a ‘fermented’ dish.

Fermented food in India goes through some amount of heating—steaming in the case of idli, light frying for dosa, and deep frying for vada, jelebi and bhatura. Excessive heat kills the probiotic. “Fermented foods should be had as a combination, some raw and some cooked,” says Devgan. “Sprouted grains, nuts and seeds and pickles are ways to have it raw. And idli and dosa will lose some benefits, but not all. Our entire diet cannot be fashioned out of raw foods; hence it is fine to have it that way.”

Natural fermentation is the oldest known technique for food preservation, developed years before the first Kelvinator rolled out of a factory. It didn’t happen on a Petri dish in a NASA lab. Humble people discovered it. Like that Sumerian barley dough left in a bowl 6,000 years ago when a thunderstorm interrupted a family’s outdoorsy bread-making. They ran for shelter, came back after a day or two to discover a soupy, fermenting liquid. They tried it, got tipsy, and beer’s born. That seems bit of a stretch, but can we write off the vast Ayurveda database on fermentation techniques for medicinal herbs? One such syrup, Sirisarista, mentioned in the Bhaishajya Ratnavali is used to treat bronchial asthma. “The probiotic effects and decreased levels of pathogenic bacteria found in fermented foods are therapeutic for the complex human gastrointestinal system. It is particularly useful for tropical nations like India for treating diarrhoea, for reducing its severity,” says food historian Pritha Sen.

Some foods like milk, beans and cruciferous vegetables are hard to digest. But hold on. Lifestyle and diet consultant Bipasha Das says, “Lactose, the natural sugar in milk is broken down during fermentation into simpler sugars—glucose and galactose. As a result, those with lactose intolerance are fine consuming fermented dairy like kefir and yoghurt.” Fermentation increases the overall nutritional value of foods. It leads to an increase in proteins, vitamins, essential amino acids and fatty acids in the food items. “Fermented foods are good for us since these help in the absorption of minerals from the gastrointestinal tract,” says Purabi Naha, food blogger from Mumbai.

The stigma attached to fermented foods is that they can be bland, boring and difficult to make at home. Plus, the strong smell due to microbial metabolic reactions, similar to rotting flesh or vegetables. While we tend to think of rotting food as a bad thing, humans have figured out how to intentionally rot foods to give them unique flavours. For the uninitiated, Akhuni, a winter delight from Nagaland, has such as a repelling odour that some people compare the smell to dirty socks.

But changing food trends are challenging perceptions of taste and helping people contemplate why one culture’s abomination is another’s delicacy. Say, for instance, fermented bamboo shoots—soft and nutritious, a condiment of choice in northeastern kitchens—had always brought trouble from landlords in Delhi’s Munirka to their tenant-students from the Northeast. More olfactory than gustatory; the distinctive smell is detectable from miles away for the unaccustomed Delhi nose. Well, people change, especially when Google tells them the gold ol’ properties of bamboo shoots—anti-inflammatory, helps in weight loss, controls bad cholesterol, and strengthens the immune system. Mr Hooda is now a regular at Humayunpur’s NE restaurants, and he drinks kefir, the foul-smelling Russian sour milk in strawberry or cranberry flavour. May his tribe increase!

***

Gundruk

A Nepali vegetarian delicacy, served as side dish or as appetiser, and can be made into a soup, too.

Ingredients

Leafy vegetables such as Rayo sag, Toriko sag (mustard), Mulako Sag (radish) and Banda kopi (cauliflower).

Process

Allow leaves to wilt for a day or two and shred them. Put leaves tightly in a clay pot, and soak them in warm water (30° Celsius). Set aside pot in a warm place. After a week, a mild acidic taste indicates the end of fermentation and the gundruk is removed and dried (in the sun, preferably). Store dried gundruk in airtight containers.

Shelf-life

several months.

Preparation

Gundruk ko jhol (soup)

- Gundruk 50 gram

- Onion 1 chopped

- Tomato 1 chopped

- Dry red chili 2

- Turmeric powder 1/2 tablespoon

- Salt 1 teaspoon/to taste

Method

Soak gundruk in water for 10 minutes. Heat oil and fry chopped onions, tomatoes, chilies. Drain soaked gundruk and fry, add turmeric powder and salt, and put 2 cups of water. Boil for 10 minutes, and serve hot with rice.

Nona Ilish or Salted Hilsa

This Bengal delicacy is similar to funazushi, the Japanese fermented carp, which is packed raw in salt tightly for a year, then dried and mixed with rice. This mixture is left to “ferment” for three years, while the rice is changed every year.

Ingredients

Hilsa cut into pieces 1kg Salt 1kg

Method

Don’t wash fish. Washing will rinse away the flavour. Layer the Hilsa pieces with salt in a clay pot, cover vessel with a muslin cloth, and set it out in a dry/sunny place for a day. Then bury the vessel in dirt for at least five days to ferment. Take out the fish, drain out the water. The fish is ready for use. It can be stored for months in an airtight container in the fridge.

Recipe

Soak fermented Hilsa pieces in water for about two hours, changing the water a couple of times to drain out salt and to soften the fish. Heat about three tablespoon of mustard oil and fry one medium-sized potato diced into cubes. Remove from the pan and keep these aside. Fry one cup diced brinjal and keep it aside. Slice one small onion and add to the oil. Fry till soft. Add the potatoes. Add one tablespoon of ginger-garlic paste, half tablespoon of turmeric and chili powder or green chili paste to taste. Fry the masala well, add some water and the fish cubes. You may add salt. But be careful because the fish has already absorbed a lot of salt. Cook till potatoes are done and the curry has thickened. Add the fried brinjal, one teaspoon lemon juice and mix well. Add green chilies. It’s done. Serve with steamed rice.

By Lachmi Deb Roy with inputs from Rituparna Kakoty