Nationalisation Of Indian Banks & Privatisation

- January 1, 1949 Reserve Bank of India nationalised

- July 1969 14 commercial banks including Central Bank of India, Punjab National Bank, Bank of Baroda, Dena Bank, Allahabad Bank, Dena Bank nationalised

- October 1975 Regional rural banks set up to promote financial inclusion

- April 1980 Six more commercial banks—Andhra Bank, Commercial Bank, New Bank of India, Oriental Bank of Commerce, Punjab and Sindh Bank and Vijaya Bank—nationalised

- 1990s Private-sector players allowed to open banks based on 1991 Narsimham Committee recommendations. ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank, Axis Bank and IndusInd Bank among others given licence. Several private banks later put under moratorium due to mismanagement and some merged with PSBs or bought over by other private banks.

- 1991-2010 25 banks became non-existent between 1991 to 2010. These include Bank of Punjab, Ganesh Bank of Kurundwad, UFJ Bank Limited, United Western Bank, Lord Krishna Bank, Sangli Bank, Bharat Overseas Bank, Parur Central Bank, Purbanchal Bank, Bank of Karad Limited, Kashinath Seth Bank, Punjab Co-operative Bank Limited, Bari Doab Bank Limited, Bareilly Bank, 20th Century Finance Corporation Limited, British Bank of Middle East, Sikkim Bank Limited.

***

Sitara Devi, 65, is mighty worried these days. A former teacher based in Pune, Devi thought she had her future financially secured with all her retirement benefits, amounting to over Rs 25 lakh, deposited at the Punjab Maharashtra Cooperative Bank till it was hit by a massive fraud a couple of months ago, forcing the country’s banking regulator to clamp severe restrictions on transactions by customers. In her 50s, Anjali works as a domestic help in the National Capital Region and she is worried too. Her relatives have been warning Anjali that she could lose all her deposits at a United Bank of India (UBI) branch at her native village near Bhopal when it merges with two other state-run banks, mostly likely by next April. Anjali does not understand how banks function, but Geeta Das, 77, a retired doctor residing in South Delhi, has a fairly good idea. Das has her own worries over the health of the public-sector bank in which she had an account for over 20 years. She recently opened an account with a private-sector bank, joining many neighbours in her colony, as a back-up protection for her hard-earned money.

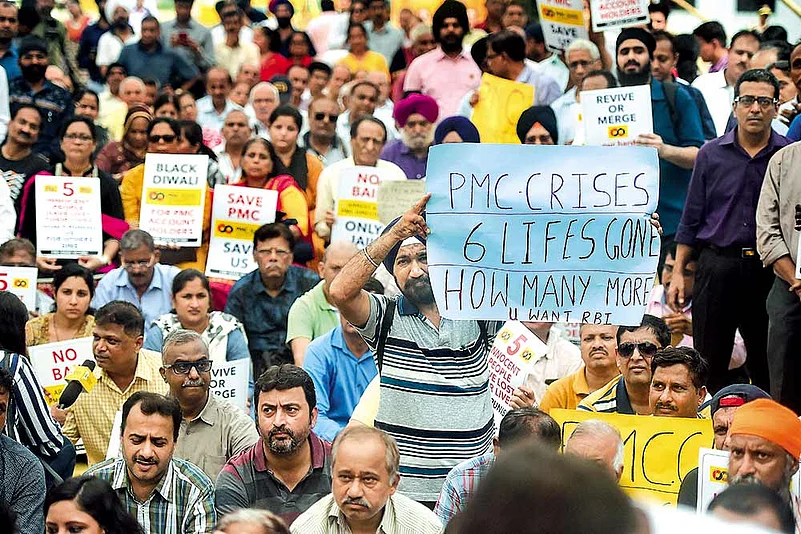

These are real people expressing real fears. Their basic question: “Is our money in the banks safe?” What happened at the PMC Bank—with a staggering 70 per cent of the loans sanctioned to the Housing Development & Infrastructure Ltd (HDIL)—is not the malaise but just one of the symptoms of the illness that afflicts India’s banking sector. And it has led to growing concerns about banks—crippled by a pile of bad loans, frauds and collapse of a major infrastructure lender, besides several other issues. For the government of the day, matters of money are always sensitive politically. At least five depositors, who had money stuck with the PMC Bank, have died since the fraud surfaced. One committed suicide.

The crisis of confidence in the banks is so palpable that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was forced to issue a statement on October 1, reassuring that the “Indian banking system is safe and stable and there is no need to panic on the basis of such rumours”, a rare comment from the banking regulator. The fears expressed by depositors are aggravated by the realisation that only up to Rs 1 lakh deposit is secured under the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation in case a bank crumbles. The limit, possibly the smallest amount of guarantee in the world, was revised some 26 years ago. The fears turned to near panic when an official letter sent to all departments of the Odisha government on October 21 spoke about “precautions to be taken when depositing government funds” in banks. Sources in the Odisha government, however blame “misreporting” for the controversy. Sources say the note was meant for officers who park excess funds borrowed from the RBI, at an interest rate of 7 per cent, in saving accounts which offer only 3 per cent interest. “Officials should withdraw only the required money, which they plan to spend over a period of time,” a source says. But the damage, it appears, has been done.

“Fear has already crept into the minds of depositors. The fear might increase and that might lead to a collapse of the banking sector, which has not happened so far in this country because we have the guarantee that public-sector banks should not be allowed to fail,” says D.T. Franco, general secretary of the All India Bank Officers’ Confederation and president of the All India State Bank Officers’ Federation. Franco says the BJP-led central government appeared inclined to follow up on the Narasimham Committee recommendations that some of the weaker banks should be allowed to die, while the stronger ones should be merged to create larger banking entities. “This government seems to following on the recommendations as seen when the Aditya Birla Idea Payments Bank was shut down (the official closure announcement was made in July this year). There was no hue and cry, probably because not many people had put their money there,” points out Franco.

Promoted by successive governments, payment banks have not been able to live up to the hype despite offering up to 2 per cent more interest compared to commercial banks. Nor are cooperative banks in the pink of health, but they still attract a large number of customers—more than 160 million, at present—who are drawn by the fact that many of them have the state government as stake holders and offer a higher rate of interest—up to to 1.5 per cent.

“The fraud in PMC Bank obviously has renewed the panic. But let us not forget that the scare was caused by the introduction of the Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance (FRDI) Bill and it’s bail-in clause,” says Priya Dharshini, senior research associate at the Centre for Financial Accountability. The bill was withdrawn by the government after widespread protests. The bail-in clause would have allowed deposits to be converted into equity—turning depositors into shareholders—thus helping the bank to overcome a crisis at the cost of its customers.

There are reports that the FRDI Bill is being reworked, with a higher deposit-insurance cover. This, along with the merger announcements of 10 major banks, increased bank charges and closing of around 2,000 bank branches because of mergers, have contributed to the lack of faith in the government. The merger agenda started two years ago, with the State Bank of India (SBI)—the largest lender in the country—amalgamating its subsidiaries. This was followed by Dena Bank and Vijaya Bank merging with Bank of Baroda. In its latest round, four more merger proposals involving 10 banks have been announced.

Opinion is divided on whether the mergers would strengthen or improve functioning of the banks. “The full impact of these mergers would take some time to show. It is expected that in a few years, systemic stability and operational-scale benefits would creep in,” says one expert, seeking anonymity. The problem with the mergers is that along with asset consolidation there is also consolidation of non-performing assets, which pose their own set of challenges, the expert adds.

Dharshini says the fear of depositors is across the board—be it commercial or cooperative banks. The public sector banks have, since nationalisation, enjoyed the trust of the people, with an implicit sovereign guarantee. “Unfortunately, this is changing. For the reasons already mentioned, and the continuation of the banking crisis, common people feel they are being looted to serve the rich,” she adds. Refusing to comment on reports of people shifting their money to private banks without supporting data, Dharshini says if that were the case, it could only be possible among the middle- and upper-middle-class customers and not necessarily among those lower down who have savings account with public-sector banks.

C.P. Chandrasekhar, professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, JNU, attributes the public fear perception to the fact that depositors “still don’t know what is going to come out from under the surface, whether it is in the PMC or the Punjab National Bank”. It was because of this fear, reflected in the markets, which led the RBI to issue a bland statement saying there was nothing to fear. According to him, a combination of things, including maybe the perception of a lack of adequate firmness and action from the government, led some people to move their money from one bank to another. Chandrasekhar feels the government appears to be going slow and almost unwilling to put in the amount of money needed to recapitalise the banks.

Krishnan Sitaraman, senior director at rating agency Crisil, feels there was no need for fears about the Indian banking sector. He points out that in the past too some cooperative banks had faced challenges and some had gone bust, but in the case of a scheduled commercial bank, no depositor would have lost money. “The bottom line is that there is a regulatory oversight and a framework that is in operation. Even when certain private banks have been under stress, the government has stepped in either to bail them out or acquire them in the public interest,” he says.

According to him, the concerns would be justified if depositors were losing money. “This is not the case with scheduled commercial banks. So, I don’t believe there is so much fear or gloom about the Indian banking sector,” Sitaraman adds. He says the worst, in fact, is over in terms of non-performing assets (NPAs), which had been a cause of concern in the past, with the peak of 11.5 per cent in March 2018. Subsequently, NPAs have been steadily coming down, touching 9.3 per cent in March 2019. “We believe by March 2020 it would be lower because some resolutions should happen under the bankruptcy code (IBC) by the end of this fiscal year,” says Sitaraman.

At least five people have died over the PMC Bank fraud.

Experts point out there will be cycles when NPAs will go up or come down, just like economic growth cycles. Over the past two fiscal years, the government has infused around Rs 2 lakh crore into public-sector banks and has announced plans to infuse a further Rs 70,000 crore this year. Of this, Rs 55,000 crore will be upfront infusion, strengthening the capital profile of public-sector banks. Sitaraman points out that after three consecutive fiscal years of losses by a number of public-sector banks, “this year we believe on an aggregate basis, public-sector banks will start making profits, while credit growth should be in double digits”.

However, the numbers are not too encouraging. Credit disbursal has slipped from 13.1 per cent in March 2019 to 11.7 per cent in June 2019 and further to 9 per cent in September. Likewise, deposits—particularly in urban areas—have shown a slide, from 10.2 per cent in March 2019 to 9.6 per cent in June 2019. Experts are hopeful credit disbursal could rise to 10 to 11 per cent by the next quarter. There are also expectations that more banks will turn profitable this year.

Geeta Chugh of S&P Global Ratings, in a recent report titled Indian Financial Sector Braces for Fat Contagion Tail Risk, says the risk of failure of a small- to mid-sized bank in India was limited. But the contagion impact of such failure would be much higher than a finance company. “We believe that the Indian government is highly supportive of the banking sector and may step in swiftly to ensure system stability. Typically, we expect the government will only intervene for large and mid-sized banks. But when paranoia is high and the contagion risks are pronounced, they may extend support to smaller banks too.”

A bank failure in the current market, she adds, could exacerbate risks. It may be cheaper for the government to support a bank than letting a shaky credit system undermine the economy. This tracks a precedent. In 2008, the RBI testified to the ICICI Bank’s fundamental strengths, allaying depositor concerns and preserving the system’s stability.

In the final analysis, even if the banks are not allowed to fail by the government, there are fears that bigger, merged banks sitting on piles of liquidity may resort to liberalised lending as in the past, overlooking the checks and balances of the RBI. The tales of NPAs and bank frauds, despite the oversight, shows a strong nexus between borrowers and top managers of lenders. If this continues to happen, depositors who have put their hard-earned money in banks may well continue to receive shocks, till a strong system of accountability is put in place.

***

Mergers And Acquisitions

- 1999 First private-sector merger between HDFC Bank and Times Bank

- 2004 Oriental Bank of Commerce acquires Global Trust Bank Limited following the stock market scam of 2001

- 2005 Bank of Punjab (BoP) and Centurion Bank (CB) merge to form Centurion Bank of Punjab (CBP)

- 2007 Lord Krishna Bank merges with Centurion Bank of Punjab

- 2008 Centurion Bank of Punjab merged with HDFC Bank

- 2016-17 SBI amalgamates with five subsidiaries and Mahila Bank

- 2018-19 Vijaya Bank and Dena Bank merge with Bank of Baroda

- 2019 Four more mergers proposed to reduce PSB number from 27 to 12. These include—

United Bank of India and Oriental Bank of Commerce with Punjab National Bank

Syndicate Bank with Canara Bank

Allahabad Bank with Indian Bank

Andhra Bank and Corporation Bank with Union Bank of India