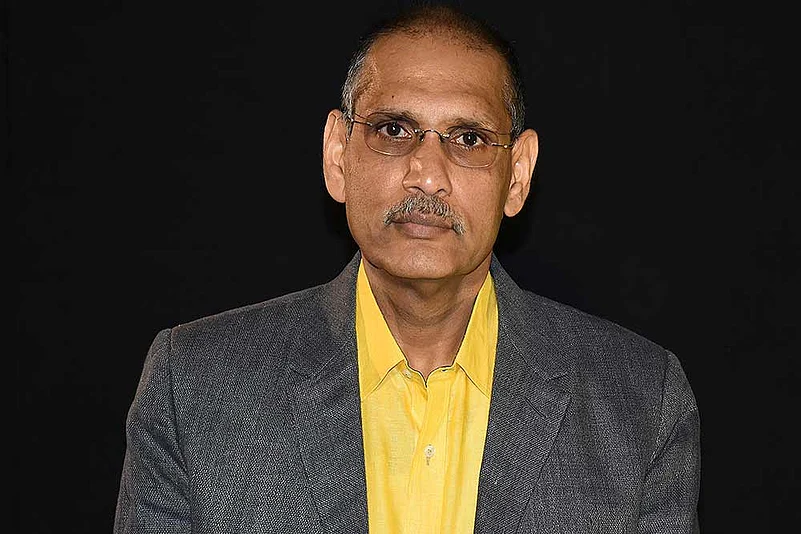

Vocational courses continue to be perceived as un-aspirational and the industry is to be blamed for not recognising them as acceptable qualifications for jobs. Dr Mukti Kant Mishra, president, Centurion University of Technology and Management, in conversation with Lola Nayar. Excerpts:

Are vocational courses coming up as feasible alternatives for a BCom or a BSc degree?

They are still perceived as un-aspirational and are not the preferred option for most youth. Traditional education leading up to a government job remains the first preference among the rural population. All the same, there is an awareness of vocational education through the Skill India mission coupled by the lack of jobs the youth face after pursuing traditional degrees. The acceptability of these courses still remains quite low, both on the demand side (student acceptability) and the supply side (INStitutional tardiness in offering such courses). The industry too has not come forward in recognising these courses as acceptable qualifications. For instance, electricians still need only an ITI certificate.

As we see it, convergence between vocational training and mainstream education (BA, BBA, B.Com, B.Sc) is the way ahead and the government has created a the National Skills Qualifications Framework (NSQF). The National Skill Development Authority (NSDA) has been given a mandate to drive this convergence. However, implementation at university and institutional level is far away from reality.

What are the changes you have introduced in training modules over the years?

Learning has to move out of the traditional mode of delivery and into labs and workshops through applied learning. However, the learning still remains incomplete until the student gets a live production environment which we call ‘action learning’. The model of ‘teaching, training, production and productivity’ is made a reality when, say, a trainee learns to do machining of aero-engine components in our CNC labs which supply components to HAL, or when our BBA students learn to solve the problems of the urban poor through our Urban Micro Business Center intervention in urban slums.

How different are your training modules from those in other universities and ITIs?

Our model’s success is based on inclusiveness. The same machine shop where engineers or diploma engineers learn how to operate a lathe machine is also used by school/college dropouts to do vocational courses in turning. Disadvantaged youth are given free training through government schemes and are linked with jobs across industrial belts. The industry is the most important stakeholder and helps us develop training infrastructure and curriculum, and we work with many players from the industry.

How successful is it to bridge the gap between conventional degree courses and B.Voc courses? Do you make frequent changes in your training course to suit market requirements?

This is an essential condition for addressing the deep rooted problems ailing our education sector. Conventional degree courses are becoming defunct by the rapidly changing needs of industry which is moving towards automation. Conventional degree courses need urgent vocationalisation and skills need to be integrated with higher education. Our university is partnering with industry to bring in this change to our traditional degree and diploma programmes. B.Voc’s focus should remain on providing higher education to people at the bottom of the pyramid by providing them multiple entries and exits. They can choose to pursue a short term vocational course and accumulate credits, work for a while and then return to complete their degree over a period of time.