- <30% unsuccessful call attempts occur during off-peak hours. Hence, excess traffic can’t really be blamed during these times.

- <40% errors in calls received occur post midnight, clearly indicating that lack of spectrum is not an issue during these times

- <36% of call-drops occur in good coverage areas. This clearly indicates that lack of tower sites not an issue in these areas.

***

This report is about 2,000 words long. You could speak it out in 12-14 minutes. But if you were to read it out over a mobile, depending on your service provider and the city you’re in, you’d end up making five to eight calls. Welcome to the world’s biggest call-drop nation—that’s what some are calling India—as networks across the country snap under the growing weight of calls and data.

The problem has plagued cellphone users for more than six months, but the authorities are finally acting—if almost a month after Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed concern at the extent of the problem and demanded corrective steps. There could be relief in sight as watchdog Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) imposes penalties and forces operators to pay compensation for call-drops. As for operators refusing to toe TRAI’s diktats, its chief R.S. Sharma says, “That’s a call we have to take: if we pass the orders, they will have to comply.” Already telcos, who had been given two weeks to get their act together, have been told their time is up. An open house on October 1 was to discuss penalties that could be imposed and compensation that could be given to customers. TRAI has also been conducting independent tests in Delhi, Mumbai and five other metros to diagnose the problems. And in what could expose the telcos, Sharma says a fact paper analysing telecom operations and deficiencies is being made public. Here are six major myths dispelled:

Myth 1: Spectrum congestion

Reality: The problem owes chiefly to non-optimal use of spectrum

Telcos get independent performance audits done for an accurate picture of network efficiency and service quality. This data is carefully hidden, aimed as the audits are at improving profitability. But one such report—by Phimetrics, a global telecom audit firm that has been conducting such audits for Indian telcos for six years—was shared with TRAI. It was also shared with the prime minister’s office, the reason for Modi cracking the whip. The report, accessed by Outlook, says: “All operators have shown an approximate 50 per cent increase in their call-drop rate compared to the past year.” It blames non-optimal spectrum use, estimating that spectrum congestion and tower shortage account for only a third (some 33 per cent) of the problem.

Spectrum congestion occurs when available bandwidth gets divided between more than the number of users it is meant to handle. Calls break, data transmission slows. But the Phimetrics report says “more than 36 per cent of call-drops occur in good coverage areas.... More than 30 per cent unsuccessful call attempts occur during off-peak hours.... More than 40 per cent of calls-received errors occur post midnight...” Clearly, spectrum congestion is not to blame.

Phimetrics head Kartik Raja also blames a change in policy of a year ago, allowing free use of spectrum instead of tying down particular bands to particular uses: data can now be sent on bands traditionally used for voice and vice versa. Predictably going where the profit is, telcos are using the most expensive (but quicker) 900 MHz band for data, which draws more revenue. Voice transfer suffers as a result, pushed to less efficient bands. This is the chief cause for call-drops. It’s not that the problem is unknown to the government. Says Union communications and information technology minister Ravi Shankar Prasad, “We are seeing a trend where voice is being ignored because data generates revenue.” And it’s neither the case that telcos don’t know the route to a solution. Cellular Operators of India chief Rajan Mathews admits that call-drops are being addressed through spectrum optimisation.

Myth 2: The call-drop problem isn’t as bad as it’s made out to be

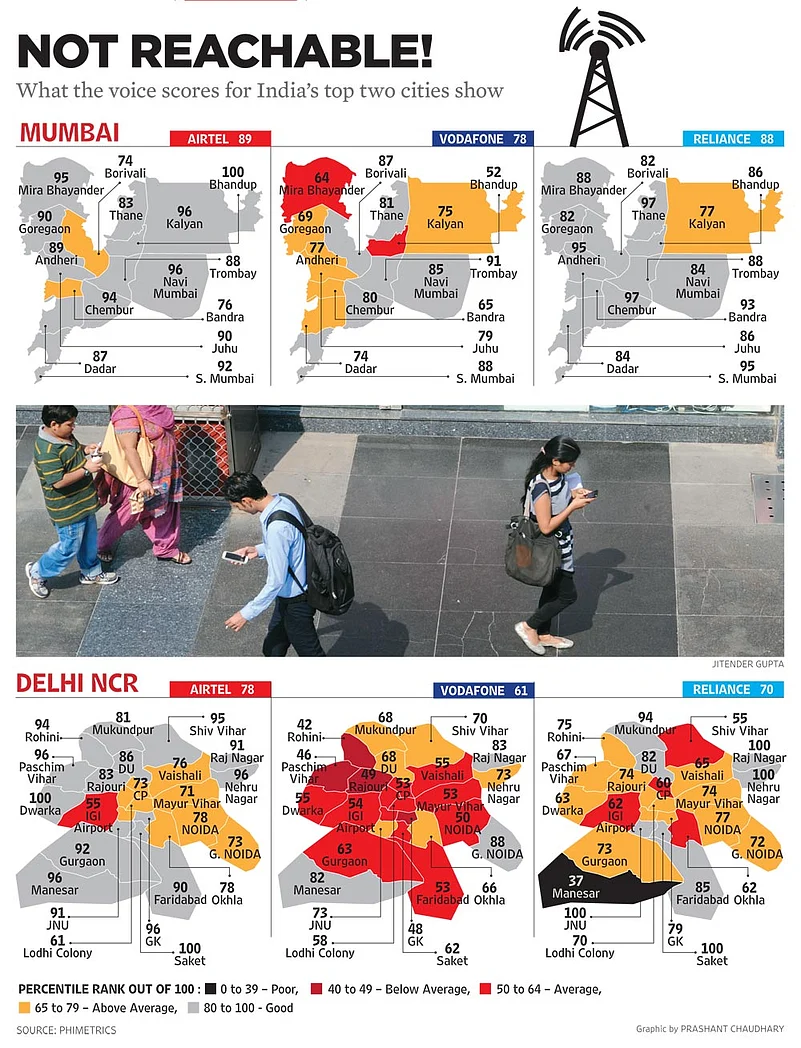

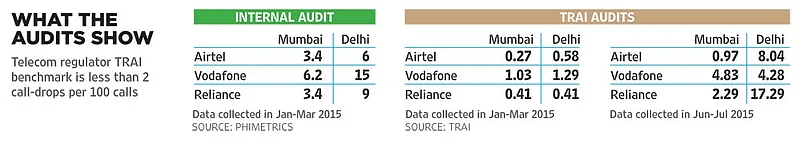

Reality: The TRAI benchmark for call-drop rates is 2 per cent or less. Internal audit data for Delhi alone (Jan-March) indicates rates of 6 per cent for Airtel, 9 per cent for Reliance and 15 per cent for Vodafone.

Despite such damning internal audit data, TRAI has been passing operators with flying colours for the past five years in its quarterly audits, with the major telcos in Delhi and Mumbai scoring either zero per cent or well below the 2 per cent benchmark. The call-drop graphs, says TRAI, rose after March but only slightly. Its report for Jan-Mar, in Mumbai, gave the following rates. Airtel: 0.27 per cent; Reliance: 0.41 per cent; and Vodafone: 1.03 per cent. In Delhi, the call-drop rates were: Vodafone 1.29 per cent; Airtel 0.58 per cent; Reliance: again 0.41 per cent.

TRAI seems to have jolted awake too with the PM’s rap. In June-July, it conducted a special audit in which the call-drop figures all shot up. Market leader Airtel’s rating, for instance, went from 0.58 to 8 per cent in Delhi! In fact, this audit showed telcos often faring worse than they did in the Phimetrics report, which is in keeping with global standards and far more expensive than the ones conducted by TRAI. “The latest TRAI data is an overreaction, to go with public sentiment,” says Raja.

Now, questions are being asked of TRAI’s audits of convenience. They had been red-flagged by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) in its report that was never tabled in Parliament: “That all service providers were able to cater to subscribers several times higher than the numbers projected...without obtaining any additional spectrum and yet maintaining quality of service pointed to the possibility of inaccuracy of data or inferior quality of work.” The CAG had also suspected collusion— “leakage of plan of survey to the operators”—between telcos and the firm TRAI sub-contracted for the audit.

Former TRAI officials say they did take action and imposed fines to the tune of Rs 25 crore. But the audits seem to be sub-par: the world over, auditors collect data for over 200 hours, covering at least 2,000 km by car, but TRAI was okay with its auditors doing 100 km at 30 kmph for three days, every three months. Cost-cutting at work: companies like Phimetrics are paid about Rs 8 lakh per audit per circle; TRAI’s payment doesn’t cross Rs 2 lakh per audit per circle. Experts say the auditors could well be using cars, phones and sims provided by the telcos they were auditing.

Myth 3: Spectrum not available

Reality: Telcos’ subscriber bases have grown 4-5 times but they have not bought spectrum to keep apace

TRAI specifies 6.2 MHz of bandwidth for every 3 lakh consumers. Now look at how the top three companies fare in Delhi alone: Airtel and Vodafone have 18 MHz each, enough for roughly 9 lakh subscribers. But Airtel has over 1.08 crore subscribers, and Vodafone about a crore. Reliance has 9 MHz catering to 82 lakh subscribers.

TRAI has known of the ever-widening subscriber base but there’s little to show it cracked the whip. Ravi Shankar Prasad is categorical: “Spectrum was never the problem. Operators need to get their act together.” Telcos, on their part, claim in unison that spectrum, if available, is in tiny, non-contiguous bands, making for inefficient service. The wireless wing of the department of telecom hasn’t addressed the problem, which former TRAI officals say can be rectified.

But when spectrum was available, what did the telcos do? In 2012, after the 2G scam, the government put up 271 MHz of spectrum for sale; more than half of it (57 per cent) went unsold. In Delhi and Mumbai, with huge loads, not one operator bought spectrum. In 2013, there were no takers for the prime 900 MHz and 1,800 MHz bands and only one operator bid for the 800 MHz band. Only in 2014 was there a scramble for spectrum, with 350 MHz being sold. Why? Because their 20-year licences issued in 1994 were ending. Without buying, they would be out of business. And if the government coffers swelled because of spectrum sale in 2015, it was because operators whose licences were issued in 1995 were buying.

A proactive CAG had made this stinging remark in its untabled report: “Operators whose subscriber numbers had already exceeded DoT benchmarks and were constantly demanding additional spectrum free of cost...did not participate in the auctions in Delhi and Mumbai and made a token participation in other circles.” Airtel, for instance, had in all made 79 appeals for more spectrum, and Reliance 30 in three years. But at the 2012 auction, Airtel bought just 1.25 MHz, only in Assam. And Reliance? Zero.

Myth 4: Call-drops don’t affect bills

Reality: It could be said 41 per cent of consumers end up paying more

Telcos never tire of claiming that call-drops are bad for business—that when a call drops, people mostly don’t make that call a second time; even if they do, they’re billed per second, so where’s the loss? They claim 71 per cent of consumers are on per-second tariff plans.

But TRAI says “only 59 per cent of the total voice usage happened on per-second basis...about 41 per cent of the total voice consumption happens on a per-minute pulse”. This means that for 41 per cent of phone users, when a call drops after even a few seconds, they get billed for the whole minute. These are mostly pre-paid customers. Reluctantly, some operators are allowing per-second billing in pre-paid plans so that they can keep customers.

Photograph by Jitender Gupta

Myth 5: Operators have invested huge amounts on infrastructure

Reality: Have they managed to catch up with the demand? No.

Since June 2013, 2G traffic has gone up 106 per cent and 3G traffic 252 per cent. Investment in non-spectrum infrastructure, however, rose by less than five per cent (during the last year). Says a TRAI white paper: “Clearly, investment has not kept pace with the usage. Thus, prima facie, it appears that lack of investment in network infrastructure by the wireless access providers may be one of the main reasons for the problem of call-drops.”

In an e-mail mass-circulated to irate customers, Bharti Airtel CEO Gopal Vittal clean forgot to mention the amount spent on augmenting non-spectrum infrastructure. “We have invested heavily behind spectrum. In the last two years, we have invested over Rs 50,000 crore on spectrum to ensure you enjoy a great network experience,” said the e-mail.

Myth 6: Not enough towers

Reality: Are the towers that telcos do have maintained well? No.

Cellphone operators have also been claiming that one of the major cause of call-drops is that there are not enough towers. This, they say, is because building owners and residents’ associations are alarmed about the health hazards of exposure to radio frequencies, the fears compounded by exaggerated reports in the media. Also that, in cities like Delhi, they are involved in legal wrangles with local self-governments, preventing them from setting up more cellphone towers. This is partly true, of course.

But, as the TRAI white paper has pointed out, since June 2013, operators’ investments in non-spectrum infrastructure has been less than five per cent of the total. And towers, which cost Rs 10 lakh-30 lakh each to set up, depending on location and height, constitute a significant component of non-spectrum infrastructure.

There are some 4.25 lakh towers across the country, each of which creates a few cells, or network coverage units, totalling some 18.25 lakh cells countrywide. An inspection report released last week said that of the 34,460 cells found “bad”, only 16,962 had been rectified.

Ravi Shankar Prasad says he is serious about telcos getting their act together, and soon—even if TRAI has to penalise non-performance. “Anyting in the interest of the consumer is a welcome step,” he says. As for the telcos, they had no comments on Outlook’s queries. Outlook also tried to get the PM’s reactions. His phone was out of coverage area.

By Meetu Jain in Delhi