Around late September last year, the Chinese government blocked WhatsApp messenger from being used in the country’s mainland. This was the last big social media app to be banned by the regime in Beijing. It marked another administrative crackdown on global social media besides internet-based services and apps to suppress free opinion in cyberspace. The action was also because of a strict internet censorship that China follows.

WhatsApp follows an end-to-end encryption system where it is difficult for anyone to tap into the messages or data that run through the app. That made it impossible for the Chinese government to tap into the data. Thus the administration has also clamped down on all apps and services that store data outside of the country and supports data that is stored only within its boundaries. China wants to monitor all internet traffic and has access to all internet-based data flowing in the country.

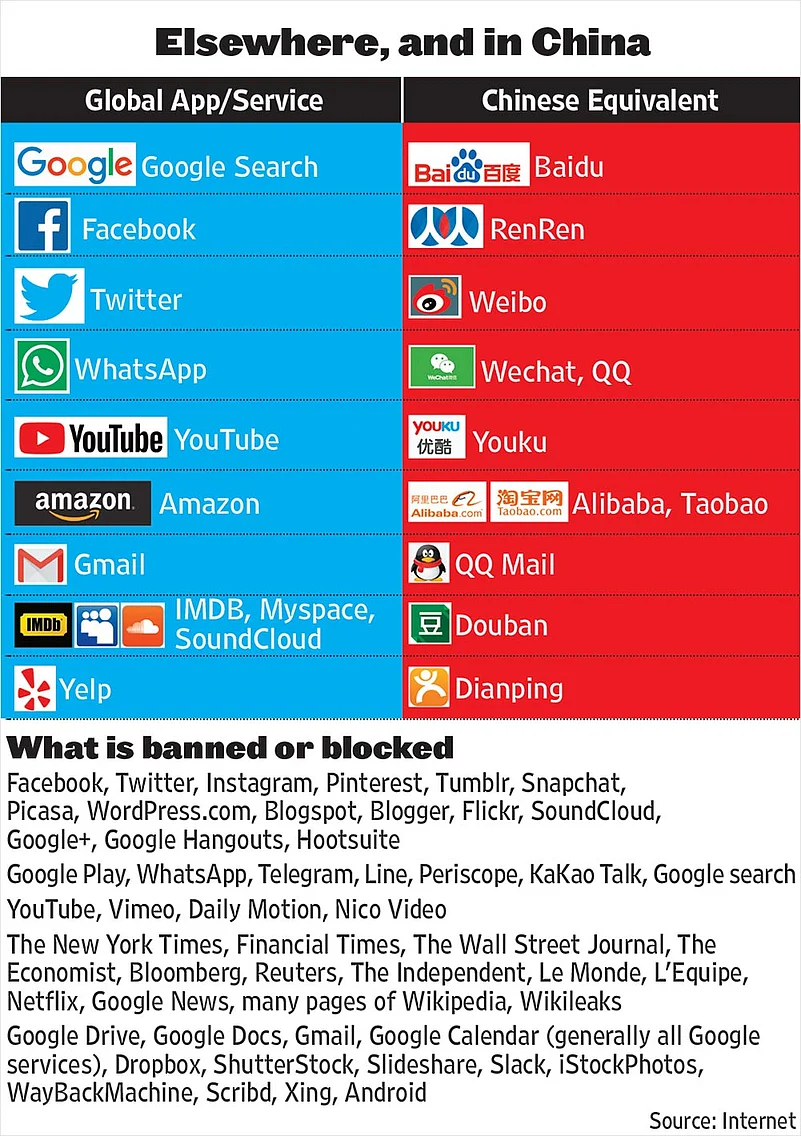

For the Chinese, WhatsApp was the last popular app to be banned. Before this, the country had blocked several apps and services that are popularly used worldwide. Facebook, which is the social media website that owns WhatsApp, was banned in China in mid-2009. Other popular internet services banned in China include social media sites like Twitter, image-sharing app Instagram, Pinterest, Tumblr, Snapchat, Picasa, WordPress, Blogspot, Blogger, Flickr, SoundCloud, Google Hangouts and Hootsuite (see graphic).

Even Google Play is banned, incapacitating Android users in China from downloading any app from Google Play Store. Other social media apps like Telegram, Periscope and Line are also not available in the country. What’s more, under the country’s strict internet censorship policy, even Google search is blocked in China, apart from video-sharing apps like YouTube and Vimeo. Also banned are Gmail and other Google services like Google Maps and Chrome. A few people manage to use some of these websites and apps through virtual private networks (VPNs), but the Chinese government has now brought in laws to restrict VPNs.

Yet there is one thing particularly interesting: the ban on these popular websites and apps has allowed Chinese websites and apps to thrive in the country. Local people widely use them. Interestingly, every global app or service has a popular Chinese equivalent. China has successfully developed its own ecosystem featuring websites, social networks and apps that are counterparts of popular global web services. The country has its own alternatives to Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and e-commerce websites. China’s Twitter equivalent is an app called Weibo, it has Baidu that is the equivalent to Google search, Wechat, which is a messenger service, and Youku, which is a video-hosting service much like YouTube.

China has an extremely popular social networking website called Renren that is the its version of Facebook, while there is Alibaba and Taobao that make up for Amazon. While Google Mail is banned in China, the country has QQ Mail as its most popular email service. “China has taken this approach for a lot of their businesses. It’s a walled garden approach,” says K.K. Mookhey, founder and CEO at Global Cyber Security Service Provider, Network Intelligence. “They will use local companies to service the Chinese customers. Now they are also going international. From a business perspective, they have done extremely well. Alibaba, Tencent and Uber competitor DD have been super successful because of the numbers and because of keeping international competition out of the market.”

Obviously, China has reasons to have a parallel universe on the internet. “The government rationale behind this is safeguarding the political affairs and prevent illegal content,” says Zakir Hussain, director, BD Soft, country partner of cyber security company Bitdefender. “Privacy is maintained and the country isn’t dependent on other sites. Rather, it encourages local social media platforms to grow and indirectly help the country’s economy. Undoubtedly, this model has worked very positively for China, making it world’s safest cyber security country.”

China, being the world’s most populous country, has, needless to say, the numbers to support these websites and apps. “China is the world’s second-largest consumer market after the USA, and its economy is more than five times the size of India’s. This by itself gives its large digital platforms enough scale and heft,” says Lloyd Mathias, former PC Marketing Head of HP (Asia-Pacific), who has first-hand experience of the Chinese market. But more than that, it is the seamless integration, he adds.

Citing an example, Mathias says Tencent, one of the largest web media companies, incorporates social networking, chat, music, e-commerce, payment systems, mobile gaming and multiplayer online games. “This end-to-end integration makes them hugely sticky for consumers, who can chat/play/shop/interact with friends/listen to music and correspondingly makes brands keen to sell on their platform hugely dependent on them. So they are immensely profitable,” he points out.

Obviously, China has tweaked the model for internet companies, eliminating the need for intrusive advertisements to generate revenue and make its internet firms profitable. “Even if you have an alternative model, the business model has to be sustainable—and the Chinese have proven it,” says Yash Mishra, founder and CEO of messaging and social networking company Voxweb. “They have shown they can be profitable without the need for ads. They call it ‘social commerce’. They have embedded e-commerce in their social media through which they generate revenue.”

All this, while having total control over the data and information flowing over the internet in that country. Abhishek A. Rastogi, partner, Khaitan & Co., notes that the Chinese model is successful to the extent that it allows the government to have strict control of the data that circulates within and goes out of the country. “It does not want to give unfettered access to companies with servers outside its territorial control,” he says. “Besides, having an unregulated network would shift power from the State to the citizens by providing an extensive forum for discussion and opinion that can result in political quicksand for the Chinese government.”

But with the government having access to all data in China, is there security of personal data? Is it protected from leakage as has happened in India? Elonnai Hickok, COO of CIS, says China has issued a personal information protection standard and there is also a cyber security law since June last year. “Its implementation has been reportedly unclear, as the law is broad and in flux. There have been reports of data breaches in China that this law/standard could help address,” she adds. “Data localisation makes it easier for the authorities to access data more easily than if it was to be stored outside the borders and not subject to its laws.”

Can the China model be imposed in India, at least to provide security of data? Most experts say India’s status as a democracy will make it impossible. More importantly, the government having access to everything may not work in India and could lead to extended litigation in times when personal data privacy is gaining mileage worldwide. “A hurdle is whether India sees itself as allowing free trade or creating a homegrown ecosystem,” says Hickok. “China’s model has many implications for freedom of expression, access to knowledge, trade and for foreign investment that need to be thought through carefully.”

Also, the nature and construct of both economies are extremely different. Vis-à-vis China, India is an open economy, thus more dependent on global economies for its business. Further, censorship on electronic media with an unreasonable restriction has been and can be challenged in the courts as a violation of fundamental rights. However, serious privacy violations and data breaches can face legal sanction. Facebook, for example, is under close scrutiny by the Indian government pursuant to recent revelation of data leaks.

One thing is clear. China has at least proved to the world that it can survive without global giants and develop its own system that makes people self-sufficient in their needs on the internet and social media. Barring government-sponsored censorship, this leaves much for India to learn.