Sudhir Panwar, a member of the Uttar Pradesh Planning Commission and professor at the University of Lucknow, was caught up in a strange, chaotic situation on Wednesday afternoon. A group of sugarcane farmers from western UP had travelled to the state capital that morning. They had arrived to meet state officials, to implore them to issue a sugarcane ‘reservation order’. This order has been long overdue this year. Without it, the sugar mills are not allowed to purchase the sugarcane crop, which is ready to be harvested.

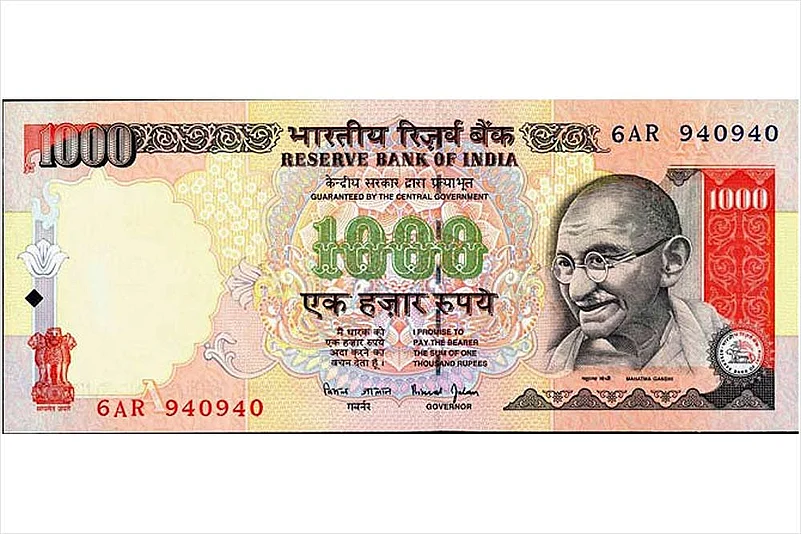

But when the farmers reached Lucknow, and as they began their meetings, they realised that their currency notes were not being accepted by shopkeepers and restaurants. The night before, the government had invalidated Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes, but those were the only denominations they had. Lucknow—like most other places in the country—was witnessing a lot of panic as the government tried to assure people that cash in the form of Rs 2000 currency notes would be available in coming days. Thus, with all the banks and ATMs closed to public dealings on Wednesday, these hungry and confused farmers finally approached Panwar. “They were wandering around with nowhere to go or eat so I arranged some Rs 4,000 in cash for them, needless to say, with great difficulty,” says Panwar.

Right now, north India’s paddy farmers are flush with cash from fresh crop sales and need to purchase seeds for the sowing season. Most of their cash—and cash is the norm in rural India—is in the form of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, the most common denominations. “I expect rural banks, which are very inefficient, to turn away these people as they try to exchange their cash for the new currency,” Panwar adds. “The current feeling is that their money has been rendered worthless overnight.”

Early morning on the same day, another scenario played out at one of north India’s prominent vegetable markets in Gurgaon, which cater to the hinterland as well as regions beyond. This mandi typically opens for business at 4 AM, starting with purchases that are on credit. Subsequently, cash purchases begin, from 6.30 AM to late into the afternoon.

On Wednesday, buyers came to the mandi with cash in the now-invalid denominations, so trading could not take off. The farmers failed to sell their produce, and the crowd was getting agitated. The mandi president then decided to accept the old denominations, just for a day.

By the end of the day’s trading, transactions were 30 per cent lower than usual. “Making the Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes invalid did cause hardship but we can take this much trouble for the better of the country,” says Inderjeet Thakran, president, Gurgaon Sabzi Association. He is only voicing a belief that many have, that the sudden ban on these denominations will curb illegal currency and black money, plus make the country safer. “Yes the impact of the government’s decision will continue for the next two or three months,” he says. “But tough decisions like this were likely. Hadn’t the Prime Minister said that black money hoarders should own up by September 30 and then not complain if the government takes tough steps.”

Another merchant, Puran Chand, from Gurgaon, says, “I have accepted at least Rs 1.25 lakh even today in Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes. It was either that or letting the vegetables rot.” The mandi relaxed the ban for a day, out of ‘compulsion’. “They will be very strict from Thursday. Today, rather than letting stocks spoil, they allowed the old currency,” says Kishanpal Yadav, another trader from Baghpat, UP.

Since cash is used in most transactions in rural areas, people there are hard pressed for now. It also remains to be seen whether this effort will bear any fruit once the Rs 2,000 currency is in circulation. “The demonetisation won’t hurt the corrupt businessman or the black money hoarder much, for his money is in real estate, overseas accounts, gold, stock and bond, or in credit cards,” says Tehseen Poonawalla, an anti-black money activist.

Midnight Strike

The NDA government led by Narendra Modi took the country by surprise when he announced through a television screen that existing Rs 500 and Rs 1000 notes will no longer be considered legal tenders from Nov 9

Panic gripped the countryside as news of the demonitisation spread. “Today the business died a slow death. We don’t know what will happen tomorrow,” says K.K. Rafique, joint secretary of the Fish Merchants Association, Vypin, Ernakulam, Kerala. Fishermen, like farmers, don’t use cheques or deal with banks. They also deal in large quantities of cash. “They need cash to buy daily rations after spending a night out at sea,” says Rafique, who could not pay his 52 workers on Wednesday for want of Rs 100 notes.

Most small eateries and other establishments in the region closed early due to disputes over payment. Some 60 boats were recalled from the high seas as merchants had only Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes. “I can’t run my business if the government rations cash at Rs 20,000,” says Habeeb Shaji, a manager at the harbour.

“Even the policemen are not accepting bribes in Rs 500 or Rs 1,000 notes,” quips RP Sethi, a prominent transporter whose trucks ply agricultural commodities between the agri-markets and farms in rural Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, and elsewhere.

Sethi says his truckers faced immediate hassles, but hopes to be over the bump once the new notes come into circulation. “A lot of people with black money in crores and crores will find their wealth rendered useless,” he says. There were some “initial hiccups,” he acknowledged. Many of his truck drivers were stranded on highways on Tuesday night, as the dhaba owners refused to accept their cash. “I called dhaba owners and promised to send money, once I get the new notes,” says Sethi.

But many others were not so calm about the change. “Can a man even buy a glass of tea or a drink of water today? There’s so much black money with wealthy businessmen and industrialists. Do you think it is they who are wandering around Kairana looking for change,” asks Tahir Hassan, a resident of Kairana in western UP and a teacher by profession.

When Hassan stepped out of his house on Wednesday, several distraught vegetable vendors approached him, requesting change for their big notes. People in these parts store cash in specific locations within every house, known as an “aala” or “kuthla”, where jewellery is also kept. “The sudden declaration of people’s hard-earned money as illegal is not democratic. Everybody here has cash savings, for the economy is farm dependent. The poor don’t even have bank accounts or IDs,” says Hassan.

Umesh Pradhan, a farmer from Shamli, says medical store owners, petrol pumps and kiranas are extorting customers under the guise of not having change. “If someone wants to make a purchase worth Rs 100, store owners are blackmailing them into buying goods worth Rs 500,” he says.

Things are also not working out for Noor Mohammad, who has come to the vegetable market in Gurgaon with Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes—he always carries his entire earnings with him, he says. “The vendors are not giving me any vegetables,” he complains. The vendor, a push-cart operator named Kushwaha, on his part, is worried about accepting invalid currency. “I used to sell produce worth Rs 3,000 everyday, but today I have only sold Rs 1,000 worth,” he says. “But where will I take these notes of Rs 1,000 and Rs 500 to exchange? Let them come with change first.”

These are only the early days of the mammoth cash purge—and a lot of people feel that it’s worth going through the hardship of initial days to serve a larger cause, while, on the other hand, just as many are outraged at this forced disruption of order. How far this will work will depend, obviously, on how soon and how well the government brings it all under control.

by Pragya Singh with Minu Ittyipe in Ernakulam